Anaheim, California

It was about 4:30pm in the afternoon when the existential despair set in.

“What do we do now?”

Blessed though we were with short queues, a lightly attended day at California Adventure came with the consequence of running out of things to do just as the sun was beginning to hang at that eyelid squinting level, at which point we sat on a bench to contemplate the emptiness of existence at California Adventure. Also so my aunt Christine could munch on a frozen banana she had been craving. By this time we had completed a loop of the entire park, checking off all the major go-to attractions from our list, and with park-hopping not included on our tickets we were now held ourselves hostage by our requirement to see all the evening shows. Had World of Color not been the big new thing in town, a foray into the possibility of packing up and leaving early might have been more seriously entertained. But our lives would be painfully incomplete if denied the chance to see Donald Duck on a 50 foot tall water screen, and thus we were stuck.

to see Donald Duck on a 50 foot tall water screen, and thus we were stuck.

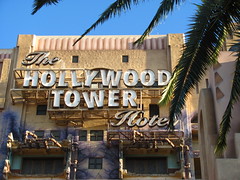

“Let’s see what there is to do in A Bug’s Land,” I said, trying to convince myself my enthusiasm was authentic as I crumpled away my park guide for the umpteenth time. Yeah, A Bug’s Land is really the park’s kiddieland section. But until the next door Cars Land comes online, a day without big crowds means children’s attractions must be enjoyed by kids and adults alike once marathon riding California Screamin’ becomes too tedious. The good news is that A Bug’s Land, as an expansion after the deficiencies of the original blueprints came to light, is one of the nicer environments in the park, mixing real, organic greenery seamlessly with larger-than-life props. It does a surprisingly competent job at making one feel like they’ve been shrunk down to a bug’s size in the middle of a compulsive hoarder’s backyard, judging by all the repurposed refuse left strewn between the giant cloverleaves towering overhead. Although, further complicating this backstory is the fact that we appear to be in the lawn of the Hollywood Tower Hotel, which pretty well dominates most of A Bug’s Land. I trust there does exist a backstory to explain this feature, and it’s not just another case of Disney California Adventure paying no attention to what is and isn’t hidden from the sightlines within their themed lands.

one feel like they’ve been shrunk down to a bug’s size in the middle of a compulsive hoarder’s backyard, judging by all the repurposed refuse left strewn between the giant cloverleaves towering overhead. Although, further complicating this backstory is the fact that we appear to be in the lawn of the Hollywood Tower Hotel, which pretty well dominates most of A Bug’s Land. I trust there does exist a backstory to explain this feature, and it’s not just another case of Disney California Adventure paying no attention to what is and isn’t hidden from the sightlines within their themed lands.

Signature attractions include Flik’s Flyers, a suspended balloon style ride, Heimlich’s Chew Chew Train, a miniature railway through the chewed out discards of yesterday’s house party, and Tuck and Roll’s Drive ‘Em Buggies, a miniature bumper cars ride. Although smaller in footprint than some of these other attractions, it was Francis’s Ladybug Boogie that I decided was most worth the shame of joining a group of kindergarteners in queue for. This is a Zamperla Demolition Derby, a ride type that would otherwise be a minor entry in the spinning teacups genre if it weren’t for a figure-eight pathway of which the mechanics behind it continue to leave me slightly baffled. The question of how the red ladybug cars make the hand-off from one spinning platform to the other is only of slightly less immediate concern than the certainty that one of these times my vehicle is going to clip the others crossing in the opposite direction, as there seem to be mere inches of clearance as they rapidly thread through each other’s pathways.

and Tuck and Roll’s Drive ‘Em Buggies, a miniature bumper cars ride. Although smaller in footprint than some of these other attractions, it was Francis’s Ladybug Boogie that I decided was most worth the shame of joining a group of kindergarteners in queue for. This is a Zamperla Demolition Derby, a ride type that would otherwise be a minor entry in the spinning teacups genre if it weren’t for a figure-eight pathway of which the mechanics behind it continue to leave me slightly baffled. The question of how the red ladybug cars make the hand-off from one spinning platform to the other is only of slightly less immediate concern than the certainty that one of these times my vehicle is going to clip the others crossing in the opposite direction, as there seem to be mere inches of clearance as they rapidly thread through each other’s pathways. Too bad the spinning mechanism was quite stubborn.

Too bad the spinning mechanism was quite stubborn.

Between my aunt and me, It’s Tough to Be a Bug was the most popular attraction in A Bug’s Land as it required the least amount of shame to stand in line for; here we were only pathetic theme park 3D movie show patrons, not even more pathetic adults riding theme park children’s rides. We just missed the previous showing, so we were stuck in the ‘underground’ waiting room for a considerable amount of time, where we amused ourselves by noting the collection of puny movie posters, re-titling classic films into insect humor (i.e. “Web Side Story”, yuk yuk). Soon the doors opened, we received our plastic “bug eye” glasses, and found our seats.

The storyline was not completely derivative of A Bug’s Life, instead expanding on the cinematic universe established by the 1998 film in a presentation that acknowledges its theme park setting. Our favorite CG animated ant not voiced by Woody Allen, Flik, directly addresses the human audience (as honorary bugs) in his presentation of the wonderful world of insects and arachnids. Rather than reprise the original ensemble voice cast for a big reunion of the franchise, the animators drew up completely new characters, including acorn weevil, soldier termite, a stink bug (extrasensory scent effect warning), and a Mexican Red-kneed Tarantula voiced by Cheech Marin. The story is puttering along in this show-and-tell mode for the first several minutes, when there’s suddenly a huge dramatic turn out of left field.

The storyline was not completely derivative of A Bug’s Life, instead expanding on the cinematic universe established by the 1998 film in a presentation that acknowledges its theme park setting. Our favorite CG animated ant not voiced by Woody Allen, Flik, directly addresses the human audience (as honorary bugs) in his presentation of the wonderful world of insects and arachnids. Rather than reprise the original ensemble voice cast for a big reunion of the franchise, the animators drew up completely new characters, including acorn weevil, soldier termite, a stink bug (extrasensory scent effect warning), and a Mexican Red-kneed Tarantula voiced by Cheech Marin. The story is puttering along in this show-and-tell mode for the first several minutes, when there’s suddenly a huge dramatic turn out of left field. Kevin Spacey’s Hopper shows up (in a considerably detailed animatronic), and promises to rain insect hellfire upon the audience for our exterminating ways. (Did this inspire the scene from Ratatouille?)

Kevin Spacey’s Hopper shows up (in a considerably detailed animatronic), and promises to rain insect hellfire upon the audience for our exterminating ways. (Did this inspire the scene from Ratatouille?)

What follows is a pretty intense battle sequence in which massive black widow animatronics aggressively plummet from the ceiling stopping inches above our heads, and a wasp attack literally has stingers being jabbed into our spines from a pneumatic device in the seat backs. Jeez, I was even starting to get a bit concerned by this complete disregard for personal space boundaries, the cinematic fourth wall completely obliterated by this point… I wondered how often they had to lead crying children for the exit. For me, I relished the unexpected twist that actually elicited some real

real involvement for a moment, and the show reasonably exceeded my expectations for what I thought would otherwise amount to just another rehashing of the familiar intellectual properties. Which it still is… but done in a way I wish more of these spin-off 3D theme park shows could take inspiration from. By the way, if we’re to assume that the story is continuous with the original feature film, then there’s some weird pataphysical subtext going on when Hopper gets eaten by a chameleon at the end, apparently oblivious to his previous fate of getting eaten by a bird. It makes one wonders if the film isn’t really a commentary on the Nietzschean concept of eternal recurrence, rather than the more convenient

involvement for a moment, and the show reasonably exceeded my expectations for what I thought would otherwise amount to just another rehashing of the familiar intellectual properties. Which it still is… but done in a way I wish more of these spin-off 3D theme park shows could take inspiration from. By the way, if we’re to assume that the story is continuous with the original feature film, then there’s some weird pataphysical subtext going on when Hopper gets eaten by a chameleon at the end, apparently oblivious to his previous fate of getting eaten by a bird. It makes one wonders if the film isn’t really a commentary on the Nietzschean concept of eternal recurrence, rather than the more convenient interpretation that the writers ran out of original ideas before the curtain call.

interpretation that the writers ran out of original ideas before the curtain call.

Turn back the clock a few hours to before the start of our existential malaise, and we were just entering Hollywood Pictures Backlot under an elegant, D.W. Griffith inspired entryway (ignore the elecTRONica signs plastered over it), awash in the glow of Sunset and Hollywood Boulevards. Palm trees, big band, Art-Deco and Spanish Revival architecture everywhere… it’s enough to make the average southern California visitor wish they could see the real thing. Maybe one day.

see the real thing. Maybe one day.

Actually, I have to admit I found this area rather sterile and oppressive, trying its hardest to replicate the form of Golden Age Hollywood, but the atmosphere is curiously lifeless and two-dimensional. The road terminating in a gigantic backdrop façade that feigns a vanishing point and the unoccupied, forced perspective rows of buildings lining the streets beg us to believe them authentic even though the originals were glimpsed on the way to the park this very morning. It seems a hollow call for remembrance of a glory day, and ultimately Disney’s incessant fixation on idealizing our history seems to say a lot more

and the unoccupied, forced perspective rows of buildings lining the streets beg us to believe them authentic even though the originals were glimpsed on the way to the park this very morning. It seems a hollow call for remembrance of a glory day, and ultimately Disney’s incessant fixation on idealizing our history seems to say a lot more about our pessimism of the present day.

about our pessimism of the present day.

One of the primary attractions fitting with the movie-making theme is the Disney Animation Building, a large indoor arcade which forms the hub for several interactive attractions. The Animation Academy we were told was a drawing class that runs a few times each hour; I’ll come back when I’m with someone that might really be into this sort of thing. The Sorcerer’s Workshop and Character Close-Up are additional interactive rooms demonstrating the process of animated character design. The real show-stopper, however, is the Pixar Zoetrope, a fully three-dimensional sculpture mounted on a giant spinning disk with strobe lights that creates the illusion of animation when set in motion. The video I captured doesn’t quite do it justice compared to seeing it in person (especially since the framerate of my camera doesn’t synch with the strobes perfectly; a warning to epileptics).

The newest experience in the building was Turtle Talk with Crush, a virtual Q&A with the sea turtle from Finding Nemo, which seats a small audience every ten minutes or so. The main purpose of this appears to be to demonstrate the virtual interactive technology, and to give a local voice actor some permanent employment, although on the technological side, the environment and 3D character isn’t much more advanced than an average videogame; the real trick seems to be coordinating the image respond to the audience on the fly, which I later found out is accomplished through the use of a digitally-linked puppet behind stage. The kids seem to like it and that’s clearly who the design was targeted for, even though the young child called on in our group was a bit reluctant to answer Crush’s questions (or answer truthfully). The actor was at least well prepared for a scenario like this and was able to keep the rest of the audience chuckling while he tried to coax a coherent reply out of the kiddo. The technology could still use a bit of tweaking, particularly in making sure that Crush is always facing the direction of the person he’s talking to. He often makes eye contact just a few feet beyond his intended subject, close but not-close-enough to still feel a bit weird. It’s sort of like talking to Michele Bachmann.

(or answer truthfully). The actor was at least well prepared for a scenario like this and was able to keep the rest of the audience chuckling while he tried to coax a coherent reply out of the kiddo. The technology could still use a bit of tweaking, particularly in making sure that Crush is always facing the direction of the person he’s talking to. He often makes eye contact just a few feet beyond his intended subject, close but not-close-enough to still feel a bit weird. It’s sort of like talking to Michele Bachmann.

Across the Boulevard midway from the Animation Building is a dark ride whose reason for being I am unable to comprehend: Monsters, Inc. Mike and Sully to the Rescue. Aside from having absolutely no thematic continuity with the rest of Sunset Boulevard, I cannot identify a target audience for this attraction. The ride is essentially a pastiche of key scenes and moments from the feature film, stitched together in a four minute experience that makes the story utterly incomprehensible to anyone not already intimately familiar with the movie. As someone who saw the film about three or four times during its original theatrical run ten years ago I was not part of that bewildered audience, but I can’t say that the attraction had any value for me either. Why? For the inverse of the same reason: because I had already seen the film! Nothing new was to be found here. It was all the same emotional cues I already knew from the film, but blitzing by one reference after another created such jarring tonal shifts that I realized the Imagineers were expecting me to meet them much more

I cannot identify a target audience for this attraction. The ride is essentially a pastiche of key scenes and moments from the feature film, stitched together in a four minute experience that makes the story utterly incomprehensible to anyone not already intimately familiar with the movie. As someone who saw the film about three or four times during its original theatrical run ten years ago I was not part of that bewildered audience, but I can’t say that the attraction had any value for me either. Why? For the inverse of the same reason: because I had already seen the film! Nothing new was to be found here. It was all the same emotional cues I already knew from the film, but blitzing by one reference after another created such jarring tonal shifts that I realized the Imagineers were expecting me to meet them much more than halfway if this was to have any coherence beyond simply being another technology showcase. It was somewhere around when we went from an intense CDA crackdown scene, to idiotic nerd banter pseudo-“comic relief”, to the slow-paced bathroom games scene, all in about the time frame of less than fifteen seconds, that I finally threw up my hands in exasperation and said, “Fuck it, dude. Let’s go bowling.”

than halfway if this was to have any coherence beyond simply being another technology showcase. It was somewhere around when we went from an intense CDA crackdown scene, to idiotic nerd banter pseudo-“comic relief”, to the slow-paced bathroom games scene, all in about the time frame of less than fifteen seconds, that I finally threw up my hands in exasperation and said, “Fuck it, dude. Let’s go bowling.”

What I find sad is that there was a lot of expensive technology invested in this attraction, but it was all wasted on an idea that contributes nothing to the cultural discourse because everything had already been done before in a medium that was better suited to the type of story. Surely somewhere out there, sitting derelict on an Imagineer’s sketchpad, there was an inspired, inventive dark ride concept that could have used this space much better. I know the Disney fanboys probably all love the ride just for the virtue of its existence, but by the end I couldn’t see it as imagined by anyone but a callous marketer. Maybe when you reduce a theme park to an extended marketing tool this is about the best we can expect, but I’ll use Tokyo Disneyland’s Hide and Go Seek version as evidence that there was a totally feasible way to incorporate the characters while doing something original that takes advantage of the dark ride format’s unique capabilities. Even the original Superstar Limo dark ride, as godawful as its description sounded, might have at least been something that my experience of it wouldn’t have felt like a complete redundancy while I was still riding it. An animatronic Roz at the end with the ability to respond to each individual carload with a seemingly personalized script was an insufficient salvo to rescue Mike and Sully. Actually, my favorite bit of the entire ride might have been a sushi menu found in the queue, with dishes such as “Swill and Sour Soup: varmint medley in miso broth”. If you’re not amused by puns, then abandon all hope ye who enter California Adventure. Moving on.

inventive dark ride concept that could have used this space much better. I know the Disney fanboys probably all love the ride just for the virtue of its existence, but by the end I couldn’t see it as imagined by anyone but a callous marketer. Maybe when you reduce a theme park to an extended marketing tool this is about the best we can expect, but I’ll use Tokyo Disneyland’s Hide and Go Seek version as evidence that there was a totally feasible way to incorporate the characters while doing something original that takes advantage of the dark ride format’s unique capabilities. Even the original Superstar Limo dark ride, as godawful as its description sounded, might have at least been something that my experience of it wouldn’t have felt like a complete redundancy while I was still riding it. An animatronic Roz at the end with the ability to respond to each individual carload with a seemingly personalized script was an insufficient salvo to rescue Mike and Sully. Actually, my favorite bit of the entire ride might have been a sushi menu found in the queue, with dishes such as “Swill and Sour Soup: varmint medley in miso broth”. If you’re not amused by puns, then abandon all hope ye who enter California Adventure. Moving on.

The physiological and psychological machinations of drop tower rides are so uniformly constant across parks and manufacturers that I’ve long since given up trying to write reviews for any individual attractions in the genre. Replacing an analysis with an unrelated joke I think speaks much more about my opinion of these rides, which isn’t that they’re not fun or important thrill icons for their parks, but that they’re such one dimensional experiences that little can be said about them. That all said, I’ve neglected to comment on the observation that drop towers are universally some of the purest working examples of catharsis, and how it is intrinsically linked to the anticipation that precedes it. It’s such a simple concept that it barely even needs elaboration, certainly not for any readers whom have experienced a drop tower first hand and screamed themselves silly on the way down. Strong emotions become pent-up and slowly accumulate, and these feelings are released once the seats are. You ascend body shaking, and you return, if not exactly at peace with the world, at least cleansed of the paralyzing anxieties on the way up. Does this speak to our fundamental situation as conscious beings towards death?

The physiological and psychological machinations of drop tower rides are so uniformly constant across parks and manufacturers that I’ve long since given up trying to write reviews for any individual attractions in the genre. Replacing an analysis with an unrelated joke I think speaks much more about my opinion of these rides, which isn’t that they’re not fun or important thrill icons for their parks, but that they’re such one dimensional experiences that little can be said about them. That all said, I’ve neglected to comment on the observation that drop towers are universally some of the purest working examples of catharsis, and how it is intrinsically linked to the anticipation that precedes it. It’s such a simple concept that it barely even needs elaboration, certainly not for any readers whom have experienced a drop tower first hand and screamed themselves silly on the way down. Strong emotions become pent-up and slowly accumulate, and these feelings are released once the seats are. You ascend body shaking, and you return, if not exactly at peace with the world, at least cleansed of the paralyzing anxieties on the way up. Does this speak to our fundamental situation as conscious beings towards death?

The Twilight Zone: Tower of Terror gets a fully written review from me not just because the scope of its intricately detailed back story and set design puts it in a league apart from ordinary drop towers, but because those simple psychological elements that I associate with nearly all drop towers are strangely absent. That’s not to say that the experience is less rich by comparison. To the contrary, this journey into the unknown is involving at so many levels that what I believe happens is the constant bedazzlement of story, technology, and detail drones out the background psychological anticipation of that singular moment of the freefall release. How can we fixate our minds on the anxiety of some future event when there’s so much happening in front of us right now?

That overload of detail begins in the lobby area that the last section of the queue winds through. It’s as impressive a piece of interior design as any you’ll find in the Disneyland Resort, the elegant interior coated with cobwebs and dust, luggage and personal affects left unattended, room keys hanging behind the reception desk. It’s an eerie snapshot of a bygone era, frozen in time. Whatever horror beset this hotel happened long ago, but witnessing the undisturbed remains curiously implicates us as indirect culprits. We’re then directed by a bellhop into a dingy private study room. With a flash of lightning, the lights dim and a television in the upper corner comes to life, introducing us to the Twilight Zone and explaining the tower’s mysterious past. The story is… uh… well, you see, we’ve entered the Twilight Zone, and, uh… the details are vague… I guess the moral is that if a building requires an emergency exit due to the presence of an extra-dimensional rift, make sure you take the stairwell and not the elevator.

you see, we’ve entered the Twilight Zone, and, uh… the details are vague… I guess the moral is that if a building requires an emergency exit due to the presence of an extra-dimensional rift, make sure you take the stairwell and not the elevator.

A recurring phenomenon I’ve noticed among story-based Disney rides is that there’s often an inability to establish causal links between narrative elements, or to define the motivating force behind an event. This is principally a problem in dark rides since the scenes have to be relatively static and the actions that transform one scene to the next must be inferred by the context (or the audience’s familiar with the story), although some times the inference is not made clear and ambiguities remain. I’ve heard this is particularly problematic with their new Little Mermaid dark ride between the dark villainy scene with Ursala and the ‘victory’ scene that immediately follows. Tower of Terror suffers from some of the same deficiencies, which is strange because it’s a highly abstract sci-fi theme and they even have a spoken voice narration running throughout the attraction.

A recurring phenomenon I’ve noticed among story-based Disney rides is that there’s often an inability to establish causal links between narrative elements, or to define the motivating force behind an event. This is principally a problem in dark rides since the scenes have to be relatively static and the actions that transform one scene to the next must be inferred by the context (or the audience’s familiar with the story), although some times the inference is not made clear and ambiguities remain. I’ve heard this is particularly problematic with their new Little Mermaid dark ride between the dark villainy scene with Ursala and the ‘victory’ scene that immediately follows. Tower of Terror suffers from some of the same deficiencies, which is strange because it’s a highly abstract sci-fi theme and they even have a spoken voice narration running throughout the attraction.

Despite Disney’s alleged mastery of storytelling, what remains unresolved for me is: what motivates the elevator drop? I understand that getting zapped into the twilight zone is the proximate moving cause that’s to account for all of the strange happenings, but why does this happen in the first place? Does it just happen randomly from time to time? Is the setting in the Golden Age of Hollywood a necessary allegorical device to the story, or was it just chosen because it looks cool? Who are the characters we see in the elevator in the preshow video? Why do they appear to be random victims, and why do we see so little of them? Is the drop a moral indictment of these people, or of the times and culture they’re living in? What role do we as spectators have in these events?

Despite Disney’s alleged mastery of storytelling, what remains unresolved for me is: what motivates the elevator drop? I understand that getting zapped into the twilight zone is the proximate moving cause that’s to account for all of the strange happenings, but why does this happen in the first place? Does it just happen randomly from time to time? Is the setting in the Golden Age of Hollywood a necessary allegorical device to the story, or was it just chosen because it looks cool? Who are the characters we see in the elevator in the preshow video? Why do they appear to be random victims, and why do we see so little of them? Is the drop a moral indictment of these people, or of the times and culture they’re living in? What role do we as spectators have in these events?

I want to pull a symbolically meaningful interpretation out of this story. It really feels like there should be some social commentary, as there’s such a strong emphasis on establishing time and place, and holding a mirror up to society’s fears through supernatural symbolism has traditionally been the function of the horror genre in literature and cinema. But no matter how deeply I try to interpret the story told through this ride, by Occam’s razor I always arrive at a conclusion that says, “well, duh, how else is a drop ride going to be explained?” I’d like to think the story necessitated the ride system, but I get the feeling it’s the other way around. Removed of the stylization, all the narration ever says is basically, “we gonna drop yo’ asses ‘cause we the Twilight Zone, bitch.”

I want to pull a symbolically meaningful interpretation out of this story. It really feels like there should be some social commentary, as there’s such a strong emphasis on establishing time and place, and holding a mirror up to society’s fears through supernatural symbolism has traditionally been the function of the horror genre in literature and cinema. But no matter how deeply I try to interpret the story told through this ride, by Occam’s razor I always arrive at a conclusion that says, “well, duh, how else is a drop ride going to be explained?” I’d like to think the story necessitated the ride system, but I get the feeling it’s the other way around. Removed of the stylization, all the narration ever says is basically, “we gonna drop yo’ asses ‘cause we the Twilight Zone, bitch.”

Rant aside, back to the ride. So, even though the preshow room makes it seem like a drop is imminent, we’re next led into a large, two-story boiler room where more queue waiting is necessary. This delay robs the urgency of the preshow somewhat when we finally strap ourselves into the service elevator with a simple seatbelt across the lap. Our vehicle retreats away from the closing doors as the shaft interior fades into a starry night sky, and then we ascend the tower, stopping at several floors for a couple of special effect chambers. One shows our vehicle facing a mirror which turns into a “ghastly” infrared reflection. This effect never seemed totally natural to me, almost more like a funhouse prop. The next scene opens up to a long hallway, with a shutting door at the end that turns the walls into another star field, leaving only the door floating in outer space. I was really impressed by this effect on the Disneyland Paris version, but it didn’t work as well here in California. I could still see the outlines of the hall between the illuminated stars, and the door never started to tumble away in space. It’s possible there were advancements in technology in the three years between debuts.

Rant aside, back to the ride. So, even though the preshow room makes it seem like a drop is imminent, we’re next led into a large, two-story boiler room where more queue waiting is necessary. This delay robs the urgency of the preshow somewhat when we finally strap ourselves into the service elevator with a simple seatbelt across the lap. Our vehicle retreats away from the closing doors as the shaft interior fades into a starry night sky, and then we ascend the tower, stopping at several floors for a couple of special effect chambers. One shows our vehicle facing a mirror which turns into a “ghastly” infrared reflection. This effect never seemed totally natural to me, almost more like a funhouse prop. The next scene opens up to a long hallway, with a shutting door at the end that turns the walls into another star field, leaving only the door floating in outer space. I was really impressed by this effect on the Disneyland Paris version, but it didn’t work as well here in California. I could still see the outlines of the hall between the illuminated stars, and the door never started to tumble away in space. It’s possible there were advancements in technology in the three years between debuts.

The suspense is weakened by the special effects busily distracting us every chance they get, but it’s not totally absent. There’s only one chance to pop the bubble of accumulated tension, and Tower of Terror blows it with a drop cycle that seems like it was programmed by the same computer chip controlling an S&S Frog Hopper. Instead of a single vertical plummet all the way down into Hades’ realm as the preshow video seemed to promise, we get a series of little weightless skips and drops, eventually pulling us back up to an open panoramic view of California Adventure, and then repeating the cycle again. It’s only the first little ten foot plunge that people scream on. After this everyone’s laughing and cheering, taking pictures, making faces for the cameras, or even taking a nap. Alright, so it’s immensely fun, I’ll grant you that.

The suspense is weakened by the special effects busily distracting us every chance they get, but it’s not totally absent. There’s only one chance to pop the bubble of accumulated tension, and Tower of Terror blows it with a drop cycle that seems like it was programmed by the same computer chip controlling an S&S Frog Hopper. Instead of a single vertical plummet all the way down into Hades’ realm as the preshow video seemed to promise, we get a series of little weightless skips and drops, eventually pulling us back up to an open panoramic view of California Adventure, and then repeating the cycle again. It’s only the first little ten foot plunge that people scream on. After this everyone’s laughing and cheering, taking pictures, making faces for the cameras, or even taking a nap. Alright, so it’s immensely fun, I’ll grant you that. But this is the Tower of Terror, not the Twilight Zone: Tower of Shits ‘n Giggles (although I would love to see that attraction name printed on a park map, somewhere). This drop program is incongruous with expectations of the story, never answering the stakes it originally set. What should have happened was that we’d get a full freefall crash to the bottom, only to encounter a plot twist as we’re reanimated from the netherworld, and then start a possessed tug-of-war between heaven and hell. But at the end of the bunny hop cycle, it’s the sound of a hubcap accidentally dropped on the cement floor that’s the most lasting, representative memory of the ride, sounding off on how what was supposed to be the existential dread of an impending cataclysmic disaster resulted in nothing more than a bit of lightweight comic relief. There’s catharsis at the end,

But this is the Tower of Terror, not the Twilight Zone: Tower of Shits ‘n Giggles (although I would love to see that attraction name printed on a park map, somewhere). This drop program is incongruous with expectations of the story, never answering the stakes it originally set. What should have happened was that we’d get a full freefall crash to the bottom, only to encounter a plot twist as we’re reanimated from the netherworld, and then start a possessed tug-of-war between heaven and hell. But at the end of the bunny hop cycle, it’s the sound of a hubcap accidentally dropped on the cement floor that’s the most lasting, representative memory of the ride, sounding off on how what was supposed to be the existential dread of an impending cataclysmic disaster resulted in nothing more than a bit of lightweight comic relief. There’s catharsis at the end, but is it for the right reasons?

but is it for the right reasons?

Perhaps current dramatic theory isn’t quite ready to go hand-in-hand with traditional amusement park ride systems for symbolic storytelling to not be rendered inconsequential once the old-fashioned stomach tickling begins. It appeared that our search for genuinely compelling narrative would lead us back to the basics and into the neighboring Hyperion Theater, where Disney’s Aladdin: A Musical Spectacular was performing this evening. This is an impressive venue unlike the standard auditorium set-ups normally found in theme parks, with double balconies and a massive satin curtain. While it clocks in a bit short of a real Broadway show at 45 minutes, in all other ways the production values are nearly indistinguishable from what you’d get for paying $100 to see The Lion King in New York. Overall I was pleased by the show, if not only because we could sit down in a climate controlled room for the better part of an hour and I could reflect on the fact that I didn’t have to get dressed up and hand over an insanely expensive ticket to see a live rendition of a children’s movie. I remember there was a time when I was six or seven years old when I could (and would) recite all the dialogue for Disney’s Aladdin from memory, so I had a slight affinity for this plot in particular. The show is a slightly abridged version with most of the dialogue unchanged, but the scenery is stylized in a way that’s less in line with the cartoon aesthetic and more approaching the new-agey bullshit of Broadway’s Lion King so they can have ventriloquists controlling the animal characters in full view of the audience.

I was six or seven years old when I could (and would) recite all the dialogue for Disney’s Aladdin from memory, so I had a slight affinity for this plot in particular. The show is a slightly abridged version with most of the dialogue unchanged, but the scenery is stylized in a way that’s less in line with the cartoon aesthetic and more approaching the new-agey bullshit of Broadway’s Lion King so they can have ventriloquists controlling the animal characters in full view of the audience.

The crowd dutifully cheers at the elephant parade down the aisles for the arrival of Prince Ali Ababwa, and they gasp in awe when Aladdin and Jasmine stunt doubles soar overhead on a wire-mounted carpet. But this sometimes too-faithful reproduction of the source material comes to a screeching halt once Genie takes the stage, whose never ceasing flow of pop-culture witticisms (including cracks at World of Color and elecTRONica) seems to belong to a completely different production. At one time, during one of the key dramatic scenes in a confrontation between Jafar and Aladdin, he literally stopped the production and forced the actors to wait frozen in their spots for several minutes so he could make shadow puppets with one of the stage lights. And you know what, that was honestly one of the best parts of the show, because when you’re copying line for line a story everyone in the audience already knows, you need to establish some ironic distance so it doesn’t feel like Disney has elevated their own story to the same level of reverence as Shakespeare. Also because at times it got to be so absurd I wondered if the whole show wasn’t really an elaborate front for an Andy Kaufman style standup routine. The audience loved it, and so did we, so they’ve obviously found a formula that works. Now, if only one of these days Disney can produce a show with an all-original plot and characters, that isn’t a line-for-line aping of their movies, that would be tops. And then after the encore we could all go ice-skating in Hell!

puppets with one of the stage lights. And you know what, that was honestly one of the best parts of the show, because when you’re copying line for line a story everyone in the audience already knows, you need to establish some ironic distance so it doesn’t feel like Disney has elevated their own story to the same level of reverence as Shakespeare. Also because at times it got to be so absurd I wondered if the whole show wasn’t really an elaborate front for an Andy Kaufman style standup routine. The audience loved it, and so did we, so they’ve obviously found a formula that works. Now, if only one of these days Disney can produce a show with an all-original plot and characters, that isn’t a line-for-line aping of their movies, that would be tops. And then after the encore we could all go ice-skating in Hell!

Comments