Valencia, California

Valencia, California

I join the queue for season pass processing. Six Flags still sells season passes online at a rate that’s less than the combined price of two one-day tickets. As I was visiting Saturday and Sunday this deal made the most sense, but I quickly regretted it when I arrived at the entrance fifteen minutes prior to opening and discovered a processing queue winding around the wall of the inner courtyard between the ticket booths and main gates that could easily take an hour or two to complete. My plan was to arrive forty-five minutes early to make sure I could get my print-off voucher exchanged for plastic in time so I wouldn’t be late for the early morning rush and get several of the major rides in before the queues fill (I am told this is an especially wise idea if one is serious about riding X2 and Tatsu as often as possible, which I was), but this queue had thrown a fine monkey wrench into those plans. Of course it was no one’s fault but my own, which made it all the more bitter pill to swallow. The plaza filled with more and more anxious teens and families, making me wonder if this was an offseason day how packed the entrance must be on a prime season weekend morning; it’s not very big. Now five minutes before they let the chain drop, an older African-American gentleman in a neon yellow uniformed shirt approached me, asking if I had already purchased a voucher. I showed him my black-and-white laser print-out I copied that morning, and he handed me a small red ticket.

(I am told this is an especially wise idea if one is serious about riding X2 and Tatsu as often as possible, which I was), but this queue had thrown a fine monkey wrench into those plans. Of course it was no one’s fault but my own, which made it all the more bitter pill to swallow. The plaza filled with more and more anxious teens and families, making me wonder if this was an offseason day how packed the entrance must be on a prime season weekend morning; it’s not very big. Now five minutes before they let the chain drop, an older African-American gentleman in a neon yellow uniformed shirt approached me, asking if I had already purchased a voucher. I showed him my black-and-white laser print-out I copied that morning, and he handed me a small red ticket.

“Well then, if you would like you can show this with your voucher at the gates over there to enter now, and you can come back any time today to get your pass processed up to a half hour after the park closes.”

I am left speechless. Really? Really really? As easy as that? I mean, it’s a simple and obvious policy to relieve unnecessary bottlenecks at the front gate, but this is Six Flags Magic Mountain we’re talking about. The place that has a reputation for closing a third of its rides to perpetual maintenance, queues running multiple hours for attractions operating at less than 50% their theoretical capacity, and a clientele that enjoys the occasional knife fight just to keep from getting bored. The amusement park where customer service is sent to die. The park so forsaken that when the new management took over a couple years ago they considered demolishing the entire premises and selling it off for its real estate rather than to continue attempting to conduct this train wreck. Thankfully, someone on Six Flags’ board decided the Mountain was still salvageable (and with eighteen coasters, had tremendous potential) and so the story I’ve been reading since 2008 or so has been that Six Flags has been making a sincere effort to turn the place around. I needed to see for myself, and lo, before I’m even inside the gates they’ve already earned a shiny gold star sticker. Well done, Magic Mountain…

I am left speechless. Really? Really really? As easy as that? I mean, it’s a simple and obvious policy to relieve unnecessary bottlenecks at the front gate, but this is Six Flags Magic Mountain we’re talking about. The place that has a reputation for closing a third of its rides to perpetual maintenance, queues running multiple hours for attractions operating at less than 50% their theoretical capacity, and a clientele that enjoys the occasional knife fight just to keep from getting bored. The amusement park where customer service is sent to die. The park so forsaken that when the new management took over a couple years ago they considered demolishing the entire premises and selling it off for its real estate rather than to continue attempting to conduct this train wreck. Thankfully, someone on Six Flags’ board decided the Mountain was still salvageable (and with eighteen coasters, had tremendous potential) and so the story I’ve been reading since 2008 or so has been that Six Flags has been making a sincere effort to turn the place around. I needed to see for myself, and lo, before I’m even inside the gates they’ve already earned a shiny gold star sticker. Well done, Magic Mountain…

When the chains drop, there’s a lively hustle to get our tickets scanned as people flood onto the main midways. I notice about 95% of visitors veer left in the direction of X2, Tatsu and Apocalypse, so I make a last second change in plans to go right instead, figuring I’d be wanting to spend the most time with those three anyway, so I shouldn’t rush to check them off my list too quickly and risk anticlimax by going from best to less. I slow my pace down when I realize I have the entire midway nearly to myself.

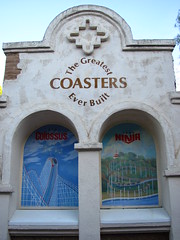

First impressions as I look around seem favorable: the asphalt has recently been power-washed, all the buildings and game pavilions are clean and tidy, and even the roller coasters towering overhead seem to have a glimmer of fresh paint that reflects gorgeously off the southern California late morning sunlight. I’m not certain if it’s just the difference in climate never having to be exposed to the snow, or if Magic Mountain really does expend more cash on repainting projects, but I was quickly reminded of Cedar Point and how many of their steel mountain ranges have a faded, patchy appearance. The axiom is that even though both parks compete for the roller coaster crown, Cedar Point is always the winner in the public’s opinion regardless of whether Magic Mountain gets ahead by a coaster for a year or two. Magic Mountain already stole the coaster crown with Green Lantern. I asked myself based on my initial impressions of how far they’ve come in three years, did I think Magic Mountain had the potential to also steal enthusiast’s hearts in another three years?

Unlikely, if only because some change on a cataclysmic scale is necessary to completely reverse stigmas, even if they can be forgotten with time. Six Flags Magic Mountain is pretty much a playground with some gigantic, modern toys sprinkled around the lawn. Except for Tatsu, nearly all of the major coasters are confined to a square or rectangular lot, lacking in the same presentation that gives some of Cedar Point’s top draws an aura of mysterious grandeur. Furthermore, in the contest that really matters, Cedar Point’s best rides are able to best Magic Mountain’s best rides with relatively little disagreement. Millennium Force vs. Goliath? Win Cedar Point. Top Thrill Dragster vs. Superman? Again, Ohio wins. Raptor vs. Batman? Mantis vs. Riddler? Perhaps more contentious, but if I were voting I’d give the nod to Cedar Point in both cases. And as awesome as X2 and Tatsu are, I personally would claim they don’t come close to touching Magnum and Maverick. Well, not too close.

Then again, that might not be the full story. While the highs at Magic Mountain are not quite as high as in Ohio, neither are the lows quite as low. Compare wooden coasters in the back corner of the park and decide for yourself who’s made better progress. Cedar Point has a handful of attractions that it seems necessary for fans to pick on so that the good stuff seems even better by comparison (even though I like Mantis more than Riddler, I know I’m in the minority to even like Mantis at all). Since Psyclone and Flashback were excised, the derided clown of Magic Mountain seems to have shifted to the fact that their B&M floorless coaster is literally built over a parking lot. True, their classic Schwarzkopf terrain looper has unnecessary restraints everyone hates, and Colossus and Viper don’t always get the most love, but none of these are subject to the same levels of vitriol that Mean Streak is subjected to on an annual basis. In an amusement park with this much stuff, those are not the worst weakest links you could have. Not by a long shot.

Compare wooden coasters in the back corner of the park and decide for yourself who’s made better progress. Cedar Point has a handful of attractions that it seems necessary for fans to pick on so that the good stuff seems even better by comparison (even though I like Mantis more than Riddler, I know I’m in the minority to even like Mantis at all). Since Psyclone and Flashback were excised, the derided clown of Magic Mountain seems to have shifted to the fact that their B&M floorless coaster is literally built over a parking lot. True, their classic Schwarzkopf terrain looper has unnecessary restraints everyone hates, and Colossus and Viper don’t always get the most love, but none of these are subject to the same levels of vitriol that Mean Streak is subjected to on an annual basis. In an amusement park with this much stuff, those are not the worst weakest links you could have. Not by a long shot.

And for the pure thrill factor, Magic Mountain might have the slight edge, at least for the demographic I assume would be reading this website. A larger percentage of Cedar Point’s coaster collection is generally categorized as family coasters, while Six Flags has been investing much more heavily in high-tech scream machines for the past decade, also allowing them to be perceived as more modernized and cutting edge. As of 2011, the median age of a Magic Mountain coaster is 13 while the median age of a Cedar Point coaster is 22. If you ride every roller coaster in the park once, you’ll have gone upside down a total of 35 times at Magic Mountain, and only 15 times at Cedar Point. I won’t conclude anything from these statistics just yet, but they do help paint the picture of the types of entertainment you’ll find at each of these two mega-parks.

heavily in high-tech scream machines for the past decade, also allowing them to be perceived as more modernized and cutting edge. As of 2011, the median age of a Magic Mountain coaster is 13 while the median age of a Cedar Point coaster is 22. If you ride every roller coaster in the park once, you’ll have gone upside down a total of 35 times at Magic Mountain, and only 15 times at Cedar Point. I won’t conclude anything from these statistics just yet, but they do help paint the picture of the types of entertainment you’ll find at each of these two mega-parks.

So ignoring the quality of the playground equipment for now (which I will review in full on the following pages) how did I find the general atmosphere of Magic Mountain? Well, the normal Six Flags style of hyperactive teenage appeal is in full force here, with plenty of meme-culture targeted advertising along the queues and midways, many of the speakers tuned to an endless stream of dance music, and lots of Looney Tune and DC Comics tie-ins which the teens seem to eat up despite conventional wisdom thinking that these would have lost their appeal around ages ten and sixteen (probably the fact that it is against conventional wisdom of what is cool that makes these properties cool to people still in their 20’s).

(probably the fact that it is against conventional wisdom of what is cool that makes these properties cool to people still in their 20’s).

But I’ll be perfectly honest: I sort of liked all of this. At other Six Flags parks that still have themed zones named things like “Yankee Harbor” or “Lickskillet” this can be very off-putting and reeks distinctly of an impersonal, money-hungry marketing department, especially when you’ve got colorful ads tackily pasted on top of old, peeling buildings formerly styled after French-Colonial architecture. Magic Mountain doesn’t have the same Angus Wynne history tie-ins; it always had a more youthful vibrancy since it started with renegade entrepreneur George Millay. In Valencia, the integration of popular culture into the park feels like it’s supposed to: it’s all an organic product of the local youth trends, and the electric flow of pop-culture everywhere becomes an important lifeblood to Magic Mountain. Normally an old snob such as myself would have nothing to do with such riff-raff, but being a few miles from the epicenter

such as myself would have nothing to do with such riff-raff, but being a few miles from the epicenter of the American entertainment machine, in a park filled with shiny, high-tech roller coaster candy (as MTV teaches us, if it ain’t pimped-out and tricked-up it ain’t worth a damn… sorry, I’m terrible at youth lingo), the youthful vibe I got from this place was infectious.

of the American entertainment machine, in a park filled with shiny, high-tech roller coaster candy (as MTV teaches us, if it ain’t pimped-out and tricked-up it ain’t worth a damn… sorry, I’m terrible at youth lingo), the youthful vibe I got from this place was infectious. Certainly a far cry from their rather homely and humble competition in Knott’s Berry Farm. And even then they know not to over-do it, and I got a wider range of cross-generational west-coast cultural influences than I might have expected. At one point I heard music playing in the queue for Goliath that

Certainly a far cry from their rather homely and humble competition in Knott’s Berry Farm. And even then they know not to over-do it, and I got a wider range of cross-generational west-coast cultural influences than I might have expected. At one point I heard music playing in the queue for Goliath that sounded a lot like The Dharma at Big Sur. I wasn’t sure, but if it was I’ll tell you this: I’ve never heard anything that good playing at Cedar Point.

sounded a lot like The Dharma at Big Sur. I wasn’t sure, but if it was I’ll tell you this: I’ve never heard anything that good playing at Cedar Point.

Speaking of Goliath, that was the first queue of the morning I found myself entering, sidestepping around the monolithic “I” that forms part of the name adorning the entry plaza, the cornerstone feature of a tropical-cum-biblical queue design that I wish was extended to the subsequent rides that would borrow its name. I believe this was the last roller coaster that drove an increase in park attendance under the old Burke

Speaking of Goliath, that was the first queue of the morning I found myself entering, sidestepping around the monolithic “I” that forms part of the name adorning the entry plaza, the cornerstone feature of a tropical-cum-biblical queue design that I wish was extended to the subsequent rides that would borrow its name. I believe this was the last roller coaster that drove an increase in park attendance under the old Burke management before the Snyder takeover. This is understandable as it is a pretty nice coaster, smooth, comfortable restraint design, tall, fast and long… and more than a decade later, the only good choice for a mega-coaster on the west coast (not counting launched or looping layouts, the next closest is Desperado on the stateline, after that you’ll be driving for a long ways east).

management before the Snyder takeover. This is understandable as it is a pretty nice coaster, smooth, comfortable restraint design, tall, fast and long… and more than a decade later, the only good choice for a mega-coaster on the west coast (not counting launched or looping layouts, the next closest is Desperado on the stateline, after that you’ll be driving for a long ways east).

Unfortunately, as I have been privileged with extensive travel east of the Mississippi, this Giovanola creation tasted a little flat to me by comparison. It was built to be the defining coaster of the year 2000, a claim that ultimately only mattered as it was the first to open that year thanks to Magic Mountain’s year-round operating season, as Millennium Force opened a few months later showing the Six Flags Corp. how to properly embrace the Y2K craze. Goliath seems even more antiquated as a result. Many of the common criticisms of Millennium Force are also present in Goliath, but without nearly as many positive qualities to mount a defense of the coaster. It’s basically a ride for fans of height and speed, with interesting dynamics a rarity and a nagging feeling that permeates the entire two-minute ride time that this isn’t the giant it once was.

first to open that year thanks to Magic Mountain’s year-round operating season, as Millennium Force opened a few months later showing the Six Flags Corp. how to properly embrace the Y2K craze. Goliath seems even more antiquated as a result. Many of the common criticisms of Millennium Force are also present in Goliath, but without nearly as many positive qualities to mount a defense of the coaster. It’s basically a ride for fans of height and speed, with interesting dynamics a rarity and a nagging feeling that permeates the entire two-minute ride time that this isn’t the giant it once was.

The first drop is symptomatic of this: 255’ is big but it’s not the biggest, and a 61° descent means much of the length of the drop follows a perfect straight line. Sometime I like ‘flat’ drops like this, but now that we’re used to drops approaching or beyond 90° on a hill half the size, it feels shallow and like a wasted opportunity to go steeper and get more airtime out of the drop. It feels more like a drop-weight launch, to be honest.

Giovanola basically copied the opening sequence from the previous year’s B&M-built Raging Bull, with the underground tunnel, elevated right fan turn, and a subsequent camelback zero-G hill crossing over the first drop, but despite having 25% more vertical distance to work with, it comes up short against the B&M effort. Judging from this coaster, the short-lived Swiss design firm Giovanola seemed reluctant to play with any sharp dynamic changes (particularly along the heartline path) or any track orientation that has one side tipped steeply above the other, possibly due to the long, inflexible 3-bench car design, and also possibly a reason they only sold three designs before they went back exclusively to fabrication.

Still, a 255’ drop into a tunnel is never a bad thing, and the following turnaround slows down enough for the banked curve at the top that even if it’s not very extreme à la Millennium Force’s punishing 122° overbank, there’s at least a nice moment to enjoy the vertigo if you’re sitting on the right side and look straight down. The following camelback was where I really got the sense that the old gal wasn’t running quite like she used to. We flirted with floater airtime for a few seconds, when I was expecting the sustained ejector negative-G’s I had once heard raved about. I’m not much a fan of B&M’s 0-G airtime even when they have elevated, tipped backed seats, and now I’m getting the same thing but with back upright and feet flat on the floor. However, I did appreciate that the hill took a different shaping approach to the standard

Still, a 255’ drop into a tunnel is never a bad thing, and the following turnaround slows down enough for the banked curve at the top that even if it’s not very extreme à la Millennium Force’s punishing 122° overbank, there’s at least a nice moment to enjoy the vertigo if you’re sitting on the right side and look straight down. The following camelback was where I really got the sense that the old gal wasn’t running quite like she used to. We flirted with floater airtime for a few seconds, when I was expecting the sustained ejector negative-G’s I had once heard raved about. I’m not much a fan of B&M’s 0-G airtime even when they have elevated, tipped backed seats, and now I’m getting the same thing but with back upright and feet flat on the floor. However, I did appreciate that the hill took a different shaping approach to the standard design favored by B&M and Intamin these days, with a long, low, flat parabola that sustains high speed the entire length. It’s not better, just different. By the time we reach the midcourse brake, I’ve adjusted my judgment criteria for Goliath from “is it better?” down to “is it different?”, hoping it will better survive my opinion as a result. The extremely hard midcourse brakes that bring the train to a near stand-still certainly weren’t doing it many favors by the original criteria.

design favored by B&M and Intamin these days, with a long, low, flat parabola that sustains high speed the entire length. It’s not better, just different. By the time we reach the midcourse brake, I’ve adjusted my judgment criteria for Goliath from “is it better?” down to “is it different?”, hoping it will better survive my opinion as a result. The extremely hard midcourse brakes that bring the train to a near stand-still certainly weren’t doing it many favors by the original criteria.

Goliath is at least different. I can’t think of any other mega-coasters except for its twin in Six Flags Over Texas that don’t even attempt a moment of airtime in the second half, opting instead for a tangled steel spaghetti bowl of helices and fan turns. We slowly slide off the brake run, the coaster exerting the most extreme moment of lateral forces on its riders in the form of hangtime off the side of the car (those in the left side seats: be creative with this moment), and then quickly regain a surprisingly lively clip through the next right fan curve, dipping down through the teal support structure.

of lateral forces on its riders in the form of hangtime off the side of the car (those in the left side seats: be creative with this moment), and then quickly regain a surprisingly lively clip through the next right fan curve, dipping down through the teal support structure.

If you’re familiar with Goliath you probably know what comes next. There’s a flat section of track, great for a moment of silence and anticipation, and then we whip around into a downhill 540° helix. This moment is famous for its dangerously strong positive G-forces that intensify as we carousel around the bend. It was not performing at suck-your-hands-down, black-out levels on my visit, but it was still without question the highlight of the ride, the one moment that really puts the “G” in “Goliath”. And it’s different. Having such a strong, sustained focus on only the positive G’s is not particularly common, at least not to the degree that if an online review were to neglect describing the forces I’d wonder if that’s because the reviewer fainted during the maneuver.

If you’re familiar with Goliath you probably know what comes next. There’s a flat section of track, great for a moment of silence and anticipation, and then we whip around into a downhill 540° helix. This moment is famous for its dangerously strong positive G-forces that intensify as we carousel around the bend. It was not performing at suck-your-hands-down, black-out levels on my visit, but it was still without question the highlight of the ride, the one moment that really puts the “G” in “Goliath”. And it’s different. Having such a strong, sustained focus on only the positive G’s is not particularly common, at least not to the degree that if an online review were to neglect describing the forces I’d wonder if that’s because the reviewer fainted during the maneuver.

My biggest peeve with Goliath is that this helix so clearly should have been the grand finale that it’s actively anti-climatic to have to tool around with another lightweight, swooshy fan and S-curve to get back to the station. Couldn’t they have relocated the centrifuge under the lift hill on the final 180° turnaround? Or better yet, keep the current helix and built another helix there so the second act has double the venom? They actually did bother to add a second helix on Titan a year later, but in the wrong place, high in the air. Well, two ground-level helices for the finale might have been a bit too much for some people. The reason the brakes are on so strongly for the midcourse is because shortly after the debut it became clear that if something weren’t done Goliath would be thinning the gene pool of weak hearts left and right. While the rabid Darwinian theorists might be appreciative of such a ride, the insurance companies I imagine would be much less so.

have been the grand finale that it’s actively anti-climatic to have to tool around with another lightweight, swooshy fan and S-curve to get back to the station. Couldn’t they have relocated the centrifuge under the lift hill on the final 180° turnaround? Or better yet, keep the current helix and built another helix there so the second act has double the venom? They actually did bother to add a second helix on Titan a year later, but in the wrong place, high in the air. Well, two ground-level helices for the finale might have been a bit too much for some people. The reason the brakes are on so strongly for the midcourse is because shortly after the debut it became clear that if something weren’t done Goliath would be thinning the gene pool of weak hearts left and right. While the rabid Darwinian theorists might be appreciative of such a ride, the insurance companies I imagine would be much less so.

Yeah, so despite it all I guess I liked Goliath, it was a change from the normal B&M speed lullabies and it’s at least a fairly long ride. Though I firmly believe it will age better as a historical oddity from an unknown company that was unnecessarily reinventing the wheel (and the traditional mega-coaster layout) without an altogether clear idea of what purpose they were achieving by doing so. Whether by accident or by design, the helix does become a classic coaster moment, and the rest is fast and smooth so it is a highly re-ridable attraction. Something I did much of my second day at Magic Mountain when the station was walk-on throughout the entire afternoon. It is one of the top ‘must rides’ while at Magic Mountain, and the competition is pretty good at this park. But the fact remains that despite the presence of a vague A-B layout sequence pattern with the midcourse brakes cleanly separating the two halves, the deepest level I could think of it by was asking if I was getting as many forces at each moment as I should have. Jesus, I hate ride reviews that are nothing more than an interpretation of the accelerometer read-outs,

without an altogether clear idea of what purpose they were achieving by doing so. Whether by accident or by design, the helix does become a classic coaster moment, and the rest is fast and smooth so it is a highly re-ridable attraction. Something I did much of my second day at Magic Mountain when the station was walk-on throughout the entire afternoon. It is one of the top ‘must rides’ while at Magic Mountain, and the competition is pretty good at this park. But the fact remains that despite the presence of a vague A-B layout sequence pattern with the midcourse brakes cleanly separating the two halves, the deepest level I could think of it by was asking if I was getting as many forces at each moment as I should have. Jesus, I hate ride reviews that are nothing more than an interpretation of the accelerometer read-outs, but that’s the best Goliath could allow me to muster.

but that’s the best Goliath could allow me to muster.

Wanting to stay one step ahead of the crowds (not that they were ever going to be particularly big), I continued downhill into the far corner to Colossus and Scream, only to discover that Colossus was closed for maintenance and Scream would be opening an hour after the rest of the park. Scream I was indifferent towards but Colossus was disappointing news, as I have never been on it and last I heard there was a rumor floating around that it could be scheduled to get a New Texas Giant style make-over in the near future, probably before I’d have a chance to return and sample the original. While I would probably be in favor of some modifications, I’d fear that a full Rocky Mountain Iron Horse make-over would carve into the symmetry of the whitewashed wooden structure, disfiguring Colossus’ best asset: its beauty. Topper track, new rolling stock and a minor reprofiling of some of the hills to improve the pacing (especially where the midcourse block brakes were built over what used to be a double dip) would be more than enough to satisfy me on a return visit. If they want 90°+ turns and flame throwers, ask Rocky Mountain to build a new coaster from scratch in some adjacent lot, it would probably cost about the same amount anyway and would be one more coaster to cement their hold on the coaster crown.

probably be in favor of some modifications, I’d fear that a full Rocky Mountain Iron Horse make-over would carve into the symmetry of the whitewashed wooden structure, disfiguring Colossus’ best asset: its beauty. Topper track, new rolling stock and a minor reprofiling of some of the hills to improve the pacing (especially where the midcourse block brakes were built over what used to be a double dip) would be more than enough to satisfy me on a return visit. If they want 90°+ turns and flame throwers, ask Rocky Mountain to build a new coaster from scratch in some adjacent lot, it would probably cost about the same amount anyway and would be one more coaster to cement their hold on the coaster crown.

None of the new-for-2011 coaster projects had opened yet when I visited, although Superman: Escape From Krypton was close. Later the first Saturday I was at the park I was taking a picture of the tower from over by the X2 bridge, and just before I hit the shutter, I noticed a big blue thing shoot up the tower. Click! Perfect timing. (That shot even made Screamscape the next day!) Apparently this was the first day they tested the launch (at least with the public around), and when I checked the internet that night I saw the fan sites were all abuzz with the same news, particularly over how far up the tower the ride was going. I definitely approve of Six Flags reinvesting in their existing attractions like on Superman, X2, and potentially Colossus to make sure they remain popular and don’t fall into disrepair (even if I’m apprehensive Colossus might be ‘improved’ too much, and have been less than wowed by some of the feedback on the east coast Bizarro transformations). Other regional theme park chains should take note; I’m curious what the return on investment of some of these projects have been. The only question I have to ask about Superman: Escape From Krypton is why didn’t they elect to keep one side of the track facing forward and one facing backward?

None of the new-for-2011 coaster projects had opened yet when I visited, although Superman: Escape From Krypton was close. Later the first Saturday I was at the park I was taking a picture of the tower from over by the X2 bridge, and just before I hit the shutter, I noticed a big blue thing shoot up the tower. Click! Perfect timing. (That shot even made Screamscape the next day!) Apparently this was the first day they tested the launch (at least with the public around), and when I checked the internet that night I saw the fan sites were all abuzz with the same news, particularly over how far up the tower the ride was going. I definitely approve of Six Flags reinvesting in their existing attractions like on Superman, X2, and potentially Colossus to make sure they remain popular and don’t fall into disrepair (even if I’m apprehensive Colossus might be ‘improved’ too much, and have been less than wowed by some of the feedback on the east coast Bizarro transformations). Other regional theme park chains should take note; I’m curious what the return on investment of some of these projects have been. The only question I have to ask about Superman: Escape From Krypton is why didn’t they elect to keep one side of the track facing forward and one facing backward? It seems they’d get double the usage out of it as you’d have to ride it twice to get the complete experience, but I guess it could lead to uneven capacity issues especially when the backwards-facing gimmick is still the exciting new draw in the coaster’s first couple of years. Green Lantern wasn’t even a hole in the ground yet when I was there. It seems this coaster went from dirt pile to media day in almost no time, from what I recall of construction updates over the spring. Personally, if Six Flags Corp wants to spend the next couple years giving aging rides makeovers and installing the occasional ZacSpin, Eurofighter or GCI, I would certainly not complain, though I’m not sure if Al Weber is going to have quite the same business philosophy as Mark Shapiro. Time will tell…

It seems they’d get double the usage out of it as you’d have to ride it twice to get the complete experience, but I guess it could lead to uneven capacity issues especially when the backwards-facing gimmick is still the exciting new draw in the coaster’s first couple of years. Green Lantern wasn’t even a hole in the ground yet when I was there. It seems this coaster went from dirt pile to media day in almost no time, from what I recall of construction updates over the spring. Personally, if Six Flags Corp wants to spend the next couple years giving aging rides makeovers and installing the occasional ZacSpin, Eurofighter or GCI, I would certainly not complain, though I’m not sure if Al Weber is going to have quite the same business philosophy as Mark Shapiro. Time will tell…

After completing the coasters along the back edge of the park with still no wait times, I was winding up the side of the mountain to Samurai Summit. This is a surprisingly pleasant part of the park, with the walkways shaded by an abundance of mature pine trees and a moment to escape from the flashy colors and wide vistas, the nearby roller coasters tantalizingly heard in all their aural magnificence, but only briefly glimpsed through the branches. At the top I joined the queue for the Ninja, which due to one-train operation had accumulated a twenty-five minute wait inside its pagoda station house. I wasn’t entirely pleased with this given the walk-on waits on everything else prior to this;

After completing the coasters along the back edge of the park with still no wait times, I was winding up the side of the mountain to Samurai Summit. This is a surprisingly pleasant part of the park, with the walkways shaded by an abundance of mature pine trees and a moment to escape from the flashy colors and wide vistas, the nearby roller coasters tantalizingly heard in all their aural magnificence, but only briefly glimpsed through the branches. At the top I joined the queue for the Ninja, which due to one-train operation had accumulated a twenty-five minute wait inside its pagoda station house. I wasn’t entirely pleased with this given the walk-on waits on everything else prior to this; heck, even X2 had a shorter line that day.

heck, even X2 had a shorter line that day.

Ninja is a bit of an oddity. It appears Arrow Dynamics were faced with severe space constraints and so they had to get creative with the station and layout. Positioned at the top of the mountain along a narrow ridge of land, the coaster has two lift hills. One at the very beginning, one at the very end, with the transfer tracks way down at the bottom of the hill. The station platform track even has a slight dogleg in the middle of it, which helps it fit into the round pagoda station. The lift hill is pretty short, a nice trick to conceal how long and fast the layout down the hillside that follows will be. The coaster paces itself quite well, much quicker than the ambling, occasionally lethargic coasters at Cedar Point and Chessington, but slower and longer than the five-second whirlwinds at Kings Island and Canada’s Wonderland. We got some reasonably decent swinging action I’m not accustomed to on the Iron Dragon, and the layout was deceptively longer than I had been anticipating. Just as I thought the brakes would be coming up, we turned around for another figure eight. Barring Eagle Fortress, the Ninja probably has the best location of any remaining suspended coaster,

at Kings Island and Canada’s Wonderland. We got some reasonably decent swinging action I’m not accustomed to on the Iron Dragon, and the layout was deceptively longer than I had been anticipating. Just as I thought the brakes would be coming up, we turned around for another figure eight. Barring Eagle Fortress, the Ninja probably has the best location of any remaining suspended coaster, with the previously mentioned uneven terrain and a plethora of vegetation growing around the track producing some close calls and keeping the layout hidden from view so we never

with the previously mentioned uneven terrain and a plethora of vegetation growing around the track producing some close calls and keeping the layout hidden from view so we never knew what was around the next turn. I still can’t memorize the layout even after riding it and viewing the POV videos multiple times.

knew what was around the next turn. I still can’t memorize the layout even after riding it and viewing the POV videos multiple times.

That said, despite how much Ninja gets right that other suspended coasters don’t, I couldn’t help but feel this installation was lacking a certain je ne sais quoi that I’ve come to expect from the genre. Perhaps it’s a sense of storytelling. With its constant direction changes, the layout is ultimately rather directionless and it’s hard to discern what exactly the coaster is about. Iron Dragon, Vampire, and especially the late Big Bad Wolf all have a very clear progression that ends with the ‘big finale’ (the pretzel lagoon turn, the underground tunnel, or the river dive), even if they always remain comparatively tame. Ninja doesn’t have that strong finish after a mid-course lift. It just wanders over and under the log flume until the cars run out of speed, making the last set of curves the weakest point in the ride, not the strongest. And while it has some good moments, it’s not the kind of thrill ride that leaves me breathless and wanting more right away like Flight Deck, Vortex and (I can only imagine!) Eagle Fortress. Ninja is balanced right in the middle of every scale, and that proves to be both a blessing and a curse. I sure as hell hope it never leaves the park anytime soon, however, as Magic Mountain would be losing a truly great (and increasingly rare) family thrill coaster.

to expect from the genre. Perhaps it’s a sense of storytelling. With its constant direction changes, the layout is ultimately rather directionless and it’s hard to discern what exactly the coaster is about. Iron Dragon, Vampire, and especially the late Big Bad Wolf all have a very clear progression that ends with the ‘big finale’ (the pretzel lagoon turn, the underground tunnel, or the river dive), even if they always remain comparatively tame. Ninja doesn’t have that strong finish after a mid-course lift. It just wanders over and under the log flume until the cars run out of speed, making the last set of curves the weakest point in the ride, not the strongest. And while it has some good moments, it’s not the kind of thrill ride that leaves me breathless and wanting more right away like Flight Deck, Vortex and (I can only imagine!) Eagle Fortress. Ninja is balanced right in the middle of every scale, and that proves to be both a blessing and a curse. I sure as hell hope it never leaves the park anytime soon, however, as Magic Mountain would be losing a truly great (and increasingly rare) family thrill coaster.

Tatsu is something of a miracle. How did we end up with such a creative interpretation of the flying roller coaster? It opened in 2006, at the tail end of one of the most loathed management regimes in theme park history. Somehow the people known for parking lot coasters managed to produce a swan song triad consisting of this, New Jersey’s El Toro and Georgia’s Goliath. While those other two rides dominate the respective wood and steel polls today, perhaps Tatsu manages to be the most mature vision of the three. It uses the natural terrain to its advantage. It does not confine its flight path to a square box. The elements are sequenced in a logical progression pattern that escalates to a well-defined climax, and finishes with a clean resolution. It alternates between moments that are serene and featherweight, and powerful and heavy.

Tatsu is something of a miracle. How did we end up with such a creative interpretation of the flying roller coaster? It opened in 2006, at the tail end of one of the most loathed management regimes in theme park history. Somehow the people known for parking lot coasters managed to produce a swan song triad consisting of this, New Jersey’s El Toro and Georgia’s Goliath. While those other two rides dominate the respective wood and steel polls today, perhaps Tatsu manages to be the most mature vision of the three. It uses the natural terrain to its advantage. It does not confine its flight path to a square box. The elements are sequenced in a logical progression pattern that escalates to a well-defined climax, and finishes with a clean resolution. It alternates between moments that are serene and featherweight, and powerful and heavy. With Tatsu, the flying roller coaster finally realized its untapped potential.

With Tatsu, the flying roller coaster finally realized its untapped potential.

This is at least the story I was telling myself before I entered the 40 minute queue for Tatsu. The reality isn’t quite as glamorous as everything stated above, but reality rarely is that way. I have some superficial aesthetic bones to pick with Tatsu’s appearance. A few problems ran deeper but I’ll get to those later. For one thing, the station structure is fugly. It’s basically a giant tin box on a very visible location on the front face of the hillside. Thankfully it’s painted in fairly neutral pastel colors so it doesn’t actively draw attention to itself, but they could have done so much more with the Japanese themed design that it makes me sad they decided to run a tab on sheet metal instead. Similarly I’m not a huge fan of the color scheme. The bright orange supports get to me. They’re too omnipresent to be painted such an sharp color. Something that would blend in with the surrounding trees and hillside better like a spring green or sky blue, would also better highlight against the sky the bright yellows and reds of the elegant, dragon-like twisting track; visually the track gets lost amid all the vertical orange bars. The vehicles at least look cool with their metallic dragon design, and I appreciated the small touches such as how a few of the large footers that came close to the midways were covered with stone mosaics. By the way, one thing I learned from my Japanese class, the ride’s name should be pronounced as “TA-tsu”, not “tat-SU” like the operators were singing into their microphones on each dispatch.

The bright orange supports get to me. They’re too omnipresent to be painted such an sharp color. Something that would blend in with the surrounding trees and hillside better like a spring green or sky blue, would also better highlight against the sky the bright yellows and reds of the elegant, dragon-like twisting track; visually the track gets lost amid all the vertical orange bars. The vehicles at least look cool with their metallic dragon design, and I appreciated the small touches such as how a few of the large footers that came close to the midways were covered with stone mosaics. By the way, one thing I learned from my Japanese class, the ride’s name should be pronounced as “TA-tsu”, not “tat-SU” like the operators were singing into their microphones on each dispatch.

With the all-clear, our seats are raised into the flying position which gets all the teenage girls onboard screaming before the train has even moved an inch forward. The lift hill is absent of any staircase or protective netting like on most inverted coasters, allowing us to face the ground directly without any protection against the vertigo. At 170′ most riders will probably have been on a taller coaster earlier in their day, but it might not feel like it at the top. Observe the strong convergence lines of the supports as your eyes trace them further down to the pathway immediately below, and then look up to witness the horizon miles away, the mountaintop location effectively doubling the altitude of the flyer’s apex.

Sitting in the front row we hang forward in our seats, halfway to upside-down, waiting for gravity to catch up. We feel awkward, and strangely a bit claustrophobic and agoraphobic at once. Wondering if this set-up foreshadows a particularly venomous beast about to strike, the tension is quickly released when we tip to our starboard side and release into smooth freefall. The pull-up at the bottom of the spiraling drop is surprisingly soft (it’s “only” 111’ long), and this curve merges seamlessly as we angle straight up

Sitting in the front row we hang forward in our seats, halfway to upside-down, waiting for gravity to catch up. We feel awkward, and strangely a bit claustrophobic and agoraphobic at once. Wondering if this set-up foreshadows a particularly venomous beast about to strike, the tension is quickly released when we tip to our starboard side and release into smooth freefall. The pull-up at the bottom of the spiraling drop is surprisingly soft (it’s “only” 111’ long), and this curve merges seamlessly as we angle straight up into the first half of the double rollover. It’s such an easy, carefree inversion, and on the exit we’re gliding nearly 100’ above terra firma thanks to the hilly terrain. Again, without any unnatural changes in direction, we turn onto our backs for the second half of the rollover mirroring the first. These first three elements merge seamlessly into one another, flowing as one continuous maneuver with a grace and perfection that only B&M could create.

into the first half of the double rollover. It’s such an easy, carefree inversion, and on the exit we’re gliding nearly 100’ above terra firma thanks to the hilly terrain. Again, without any unnatural changes in direction, we turn onto our backs for the second half of the rollover mirroring the first. These first three elements merge seamlessly into one another, flowing as one continuous maneuver with a grace and perfection that only B&M could create. In fifteen seconds Tatsu has already accomplished a greater sensation of flight than John Wardley managed to convey with his entire layout in Air, and we’ve still got another two-thirds to complete.

In fifteen seconds Tatsu has already accomplished a greater sensation of flight than John Wardley managed to convey with his entire layout in Air, and we’ve still got another two-thirds to complete.

The flow is broken for a brief moment as we charge down the back side of the mountain towards a midway, the forces developing a potential for a sharper edge as we soar up into a tall horseshoe turnaround. This is another moment in which the flying seat design is allowed to show its full strength, as everyone is afforded a front seat view looking across the entire park, the sense of freedom and flight still pure but with a bit more urgency.

as we charge down the back side of the mountain towards a midway, the forces developing a potential for a sharper edge as we soar up into a tall horseshoe turnaround. This is another moment in which the flying seat design is allowed to show its full strength, as everyone is afforded a front seat view looking across the entire park, the sense of freedom and flight still pure but with a bit more urgency. Coming out of this turn over the station and maintenance lot (this scenery could have been improved) the flying beast surprises with an uncharacteristically acute fore-and-aft torque onto our sides as we quickly scoot around a 90° banked turn threaded through bright orange supports. We’re still soaring, but we’re beginning to relinquish

Coming out of this turn over the station and maintenance lot (this scenery could have been improved) the flying beast surprises with an uncharacteristically acute fore-and-aft torque onto our sides as we quickly scoot around a 90° banked turn threaded through bright orange supports. We’re still soaring, but we’re beginning to relinquish control over our flight path as we’re yanked in unexpected directions. We slow, a long moment of uneasy serenity as if our winged beast has caught an updraft and is surveying the land for prey. We’re suddenly about 125’ in the air thanks to the steeply uneven land, looking at the track at the bottom of the signature pretzel loop, and realize we’re dangerously close to the edge of the calm before the storm.

control over our flight path as we’re yanked in unexpected directions. We slow, a long moment of uneasy serenity as if our winged beast has caught an updraft and is surveying the land for prey. We’re suddenly about 125’ in the air thanks to the steeply uneven land, looking at the track at the bottom of the signature pretzel loop, and realize we’re dangerously close to the edge of the calm before the storm.

It’s impossible to prepare for Tatsu’s pretzel loop. Hell, I’ve been on all three of the Supermen: Ultimate Flight clones which each have their own pretzel loop, and I was still unprepared for this one. The scale and force is on an entirely different level from anything I’ve ever experienced on a flying coaster before. Having spent the entire ride up to this point lying on our chests, when the train crests the pretzel loop our situation quickly becomes one of weightlessness as we lift up off our restraints. The dragon dives straight down for the kill, turning our orientation completely upside down as the train dives 90 degrees down. Quite rapidly, that ‘weightless’ force keeps pressing against us as the loop begins to bottom out, morphing back into lung-crushing G-forces along the opposite axis as we’re pulverized into our seat backs at the bottom of the loop. Because the flying position has us oriented to the track differently, traditional concepts such as “positive G-force” and “negative G-force” (at least as they affect the body) become skewed into something very different, and the pretzel loop is where this difference is most clearly highlighted. It’s tough to describe the full range of sensation in words, so I will simply summarize the force analysis to noting that after my first ride,

becomes one of weightlessness as we lift up off our restraints. The dragon dives straight down for the kill, turning our orientation completely upside down as the train dives 90 degrees down. Quite rapidly, that ‘weightless’ force keeps pressing against us as the loop begins to bottom out, morphing back into lung-crushing G-forces along the opposite axis as we’re pulverized into our seat backs at the bottom of the loop. Because the flying position has us oriented to the track differently, traditional concepts such as “positive G-force” and “negative G-force” (at least as they affect the body) become skewed into something very different, and the pretzel loop is where this difference is most clearly highlighted. It’s tough to describe the full range of sensation in words, so I will simply summarize the force analysis to noting that after my first ride, I was sure to empty my pockets before getting on again.

I was sure to empty my pockets before getting on again.

The following zero-G roll is the one element in Tatsu’s oeuvre that I’m not entirely sure if I like. With the short lead-in and fast heartline rotation in a high-altitude setting, this could have been an amazing element on a standard inverted coaster, but with the flying cars the impact seems neutered. Not that it’s a bad element, but coming seconds after the pretzel loop it strikes me as a half-realized idea that was inserted in the wrong place on the wrong coaster, lacking the sense of flow and sequence that the other elements before it all had. However the final maneuver, a slow-paced helix situated high above Magic Mountain plaza, contextualizes these maneuvers to fit as the descending action and then resolution to the layout narrative. I guess it doesn’t help that even in traditional storytelling I’m generally skeptical about the role and importance of descending action, but the resolution is always important. Therefore the helix is more effective by this interpretation, as I genuinely had a sense of calming catharsis in those final moments soaring high over the ants of people watching us from below. There’s a small upward skip into the brakes, which slow us most of the way before a dipped banked turn realigns us with the station and the final set of brakes reigns our winged beast back to earth.

situated high above Magic Mountain plaza, contextualizes these maneuvers to fit as the descending action and then resolution to the layout narrative. I guess it doesn’t help that even in traditional storytelling I’m generally skeptical about the role and importance of descending action, but the resolution is always important. Therefore the helix is more effective by this interpretation, as I genuinely had a sense of calming catharsis in those final moments soaring high over the ants of people watching us from below. There’s a small upward skip into the brakes, which slow us most of the way before a dipped banked turn realigns us with the station and the final set of brakes reigns our winged beast back to earth.

A central reason why I’ve felt every other stateside B&M flyer has failed in some regard is that the pretzel loop is too powerful of an element to put in the beginning of the layout, causing the ride to blow its wad too early and then spend the rest of the layout literally sweeping back and forth to clean up the mess (many apologies for the metaphor). By holding what is clearly the centerpiece element that everyone talks about back two-thirds of the layout, the flying coaster takes on a symphonic quality as it goes through its movements to reach a crescendo and then resolution. It begins with the ominous but ambiguous tones of the prelude (the vertigo-inducing lift hill climb), before the symphony begins with the bright consonant tones of the first drop and rollovers, intensifying development with the horseshoe turn and fast left banked turn, silencing for a brief middle bridge before reaching

B&M flyer has failed in some regard is that the pretzel loop is too powerful of an element to put in the beginning of the layout, causing the ride to blow its wad too early and then spend the rest of the layout literally sweeping back and forth to clean up the mess (many apologies for the metaphor). By holding what is clearly the centerpiece element that everyone talks about back two-thirds of the layout, the flying coaster takes on a symphonic quality as it goes through its movements to reach a crescendo and then resolution. It begins with the ominous but ambiguous tones of the prelude (the vertigo-inducing lift hill climb), before the symphony begins with the bright consonant tones of the first drop and rollovers, intensifying development with the horseshoe turn and fast left banked turn, silencing for a brief middle bridge before reaching the thundering climax of the 124’ pretzel loop, and finishing with a coda that resolves tension and restores harmony. The topographical interplay and resultant variable speeds are absolutely essential to allow for such a progressive structure to prevent a ride that doesn’t just diminuendo the whole way like so many B&M designs tend to do. Although the first drop is 111’ feet deep, the bottom of the pretzel loop is a full 263’ feet below the crest of the lift hill. Personally, I find that statistic to be absolutely incredible.

the thundering climax of the 124’ pretzel loop, and finishing with a coda that resolves tension and restores harmony. The topographical interplay and resultant variable speeds are absolutely essential to allow for such a progressive structure to prevent a ride that doesn’t just diminuendo the whole way like so many B&M designs tend to do. Although the first drop is 111’ feet deep, the bottom of the pretzel loop is a full 263’ feet below the crest of the lift hill. Personally, I find that statistic to be absolutely incredible.

And yet I feel guilty because I’ve been describing a roller coaster that I should conclude to be a top ten ride, but after twelve rides over two days I had to be honest with the fact that it didn’t quite sing top ten to me. Something essential was missing. For as much as I enjoyed comparing it to a symphony, it was a symphony that lasts only 45 seconds from the first movement to the final chord. Roller coasters are able to communicate a lot more in a shorter

And yet I feel guilty because I’ve been describing a roller coaster that I should conclude to be a top ten ride, but after twelve rides over two days I had to be honest with the fact that it didn’t quite sing top ten to me. Something essential was missing. For as much as I enjoyed comparing it to a symphony, it was a symphony that lasts only 45 seconds from the first movement to the final chord. Roller coasters are able to communicate a lot more in a shorter period of time due to the increased brain activity in response to the adrenaline, but especially for a ride that spends at least half the layout toning the adrenaline down in favor of graceful aerobatics, I think that’s simply not enough time to make the full emotional connection this type of ride needs to make. I would still like to see the flying equivalent of the Big Bad Wolf, with a long layout broken between two lift hills and the action spread out over two minutes in length, but given the engineering costs already involved with this technology that gets expensive. Also, after multiple rerides the pretzel loop was becoming the dominating feature in my psychological relationship to the coaster, muting the softer features as I could only think about getting to or coming from that loop. In a weird way, it’s almost too good of an element.

period of time due to the increased brain activity in response to the adrenaline, but especially for a ride that spends at least half the layout toning the adrenaline down in favor of graceful aerobatics, I think that’s simply not enough time to make the full emotional connection this type of ride needs to make. I would still like to see the flying equivalent of the Big Bad Wolf, with a long layout broken between two lift hills and the action spread out over two minutes in length, but given the engineering costs already involved with this technology that gets expensive. Also, after multiple rerides the pretzel loop was becoming the dominating feature in my psychological relationship to the coaster, muting the softer features as I could only think about getting to or coming from that loop. In a weird way, it’s almost too good of an element.

Tatsu was a miracle to have, still in my opinion by far the best flying roller coaster in the world, and easily one of the top three rides at Magic Mountain. It is in no way an unsuccessful ride, as any changes I could make to it if given the chance would nearly all be superficial. It is the first and only flying coaster to actually deliver everything the genre had always promised, and any shortcomings of Tatsu I think are fundamental shortcomings of the flying coaster. They are, nevertheless, shortcomings, and my search for the roller coaster at Six Flags Magic Mountain wasn’t over yet.

Comments