Wisconsin Dells, Wisconsin

Picture this: A family owned and operated amusement park in rural midwestern America, starting from modest means, builds itself into a successful theme park destination for people from all over the region. The theme chosen for the park is one of personal significance, although in many ways it’s a token theme because the park is built in a forested, hilly landscape, which they fill with the best wooden roller coasters their limited funds can buy. Their first 1995-built roller coaster from Custom Coasters is widely praised by enthusiasts despite its small size due to a creative layout that makes full use of the available terrain. Their follow up coaster, although larger, has more conventional thrills that don’t quite better its predecessor but make it a welcomed addition to the park nevertheless. It wasn’t until CCI reformed into the

Picture this: A family owned and operated amusement park in rural midwestern America, starting from modest means, builds itself into a successful theme park destination for people from all over the region. The theme chosen for the park is one of personal significance, although in many ways it’s a token theme because the park is built in a forested, hilly landscape, which they fill with the best wooden roller coasters their limited funds can buy. Their first 1995-built roller coaster from Custom Coasters is widely praised by enthusiasts despite its small size due to a creative layout that makes full use of the available terrain. Their follow up coaster, although larger, has more conventional thrills that don’t quite better its predecessor but make it a welcomed addition to the park nevertheless. It wasn’t until CCI reformed into the Gravity Group that they partnered up to make a record-breaking attraction that could be remembered by enthusiasts for years to come.

Gravity Group that they partnered up to make a record-breaking attraction that could be remembered by enthusiasts for years to come.

Sound familiar? Obviously I speak of Wisconsin’s Mt. Olympus Theme Park (formerly Big Chief Carts and Coaster), but it could easily be mistaken for blood-buddies with the beloved Holiday World in Santa Claus, Indiana. The two parks share much in common, and I would even go so far as to claim that in some ways, Mt. Olympus was better than Holiday World at making a business that could appeal to both families and enthusiasts. While Holiday World only has three thrilling wooden coasters, Mt. Olympus had that number matched a couple years in advance and even added a fourth, family-friendly wooden coaster for younger guests who still didn’t measure up to the 48” restriction on the bigger rides. And while Holiday World complemented their coasters with only a fairly tame, generic collection of traditional flat rides, Mt. Olympus became true innovators in their field with an extensive line-up of elaborate, multi-leveled go-karts all included with admission; carving out a unique niche not equaled anywhere else in the amusement industry. Even the Koch’s Christmas theme was something of an inevitable marketing byproduct given the name of the town and the many disappointed children who visited before 1946, while the Laskaris’s Greek theme was a much more personal proclamation of their familial heritage, proudly asserting an immigrant’s story of the American Dream

Mt. Olympus was better than Holiday World at making a business that could appeal to both families and enthusiasts. While Holiday World only has three thrilling wooden coasters, Mt. Olympus had that number matched a couple years in advance and even added a fourth, family-friendly wooden coaster for younger guests who still didn’t measure up to the 48” restriction on the bigger rides. And while Holiday World complemented their coasters with only a fairly tame, generic collection of traditional flat rides, Mt. Olympus became true innovators in their field with an extensive line-up of elaborate, multi-leveled go-karts all included with admission; carving out a unique niche not equaled anywhere else in the amusement industry. Even the Koch’s Christmas theme was something of an inevitable marketing byproduct given the name of the town and the many disappointed children who visited before 1946, while the Laskaris’s Greek theme was a much more personal proclamation of their familial heritage, proudly asserting an immigrant’s story of the American Dream to a population that otherwise would never have noticed or cared.

to a population that otherwise would never have noticed or cared.

Yet for all the potential each had to be small park treasures within the coaster community during their formative years, if you were to visit both theme parks today it would be clear that somewhere down the road Mt. Olympus split paths from Holiday World and things went very, very wrong.

Many parks get worse with age due to outmoding and neglect. Mt. Olympus is one of the few places I’ve been to which has been actively working to be worse than it was on my previous visit during Hades’ debut year. Of course, even in 2005 it was never an ideal model of hospitality business. Almost every attraction had underserved capacity, low HR standards were generally reflected in their employee’s commitment to their job, and the entire infrastructure was awkward and needed improvement. And they’ve had a few good ideas since 2005 here and there. The Parthenon indoor rides park makes sense to have in an unpredictable climate; you can remotely receive your hotel card from within the park and use it or your wristband as a debit card; and the Night at the Theme Park (basically a nightly upcharge ERT session1 on a few of the major attractions) is an enthusiast-friendly concept and something I’d love to see implemented at Holiday World. (Notice, however, that all of these good ideas are still very clearly profit-motive driven.) But as soon as we entered the parking lot, it was clear that some mistakes had been made since last time. Big mistakes.

Of course, even in 2005 it was never an ideal model of hospitality business. Almost every attraction had underserved capacity, low HR standards were generally reflected in their employee’s commitment to their job, and the entire infrastructure was awkward and needed improvement. And they’ve had a few good ideas since 2005 here and there. The Parthenon indoor rides park makes sense to have in an unpredictable climate; you can remotely receive your hotel card from within the park and use it or your wristband as a debit card; and the Night at the Theme Park (basically a nightly upcharge ERT session1 on a few of the major attractions) is an enthusiast-friendly concept and something I’d love to see implemented at Holiday World. (Notice, however, that all of these good ideas are still very clearly profit-motive driven.) But as soon as we entered the parking lot, it was clear that some mistakes had been made since last time. Big mistakes.

The parking lot is big mistake. Hell, I doubt Cedar Point has as many parking spaces as Mt. Olympus. It was big in 2005, filling the entire infield between Hades’ drop and the turnaround near the Wisconsin Dells Parkway. It has now been expanded to wrap all the way around Zeus’s turnaround, over near the back side of Hades, and past the Poseidon’s Go-Karts. Maybe five rows near the front entrance were filled. This begs several questions. The first is: when on earth does Mt. Olympus get so crowded that they could justify the enormous cost of the overflow parking capacity? Second, supposing they can fill this entire lot on some days,

The parking lot is big mistake. Hell, I doubt Cedar Point has as many parking spaces as Mt. Olympus. It was big in 2005, filling the entire infield between Hades’ drop and the turnaround near the Wisconsin Dells Parkway. It has now been expanded to wrap all the way around Zeus’s turnaround, over near the back side of Hades, and past the Poseidon’s Go-Karts. Maybe five rows near the front entrance were filled. This begs several questions. The first is: when on earth does Mt. Olympus get so crowded that they could justify the enormous cost of the overflow parking capacity? Second, supposing they can fill this entire lot on some days, how do the amusement and water parks not far exceed maximum capacity? All of the roller coasters are four-or-five car, single train operations that don’t exceed 500 people per hour, and the go-karts and upcharge attractions are even worse. Is it all for the water park and hotels (which already have their own parking lots)? And thirdly, how is this not an example of (at best) bad taste and (at worst) bad business ethics? I know tree huggers can be annoying, but when you clear that many acres of forest for nothing of added value, and effectively transform what was once a scenic wooded park into a deserted island amidst a sea of asphalt, I have to think even the biggest “global warming is a lie” Republicans would find something distasteful about that managerial decision.

how do the amusement and water parks not far exceed maximum capacity? All of the roller coasters are four-or-five car, single train operations that don’t exceed 500 people per hour, and the go-karts and upcharge attractions are even worse. Is it all for the water park and hotels (which already have their own parking lots)? And thirdly, how is this not an example of (at best) bad taste and (at worst) bad business ethics? I know tree huggers can be annoying, but when you clear that many acres of forest for nothing of added value, and effectively transform what was once a scenic wooded park into a deserted island amidst a sea of asphalt, I have to think even the biggest “global warming is a lie” Republicans would find something distasteful about that managerial decision.

The wooden coaster Zeus is perhaps the biggest victim. I once considered it a top tier coaster partly because at night it matched the best “fly-thru-the-woods” moments of The Raven or The Beast. The 1997 built CCI coaster has never gotten much love from enthusiasts mostly due to a simple L-shaped out-and-back layout that lacks in originality what it makes up for in brevity. But something about it clicked with me the last time I rode it, and at the end of the trip I had Zeus listed as my second favorite wooden coaster in the Dells. Perhaps in part because of its simplicity, it was one of the first layouts that made me keenly aware of the value of progression patterns and element sequencing in constructing a good coaster. There were two very different sides to Zeus: (1) the inline, airtime filled hills; and (2) the laterally forceful flight through the forest in the turnaround. It followed a clean and effective pattern: 1-2-1. I later realized it could be expanded further as 2-1-2-1-2, with the bookending unbolded 2’s being the weaker swooping turnarounds at the beginning and end of the layout. And what made this alternating pattern work was that both the airtime and the forested turnarounds

turnarounds were immensely fun, although for radically different reasons.2

were immensely fun, although for radically different reasons.2

It was therefore a little bit soul-crushing to see Zeus now more closely resembling Six Flags Magic Mountain’s Scream than the terrain coaster I remembered. The dense woods this coaster once flew through are gone, replaced with empty parking lot. Just a few small patches remain behind the ride and in the center of the turnaround. It already lost a little when Hades and the first phase of the lot were built, but forest around the turnaround was still as dark as a starless summer night ride on the Raven.

Now it’s just decimated. The elegant pattern I outlined above completely falls apart.

falls apart. With no terrain element, the turnarounds become just another device to get us pointed in the opposite direction with a few lateral forces, and the airtime hills dominate the appeal of the ride. Even ignoring any pattern analysis, the ride simply sucks a lot more as a parking lot coaster than it does as a terrain coaster. On full display out in the open, there’s no longer any sense of mystery and the only surprise remaining is a double-dip set in a small ditch on the return run.

With no terrain element, the turnarounds become just another device to get us pointed in the opposite direction with a few lateral forces, and the airtime hills dominate the appeal of the ride. Even ignoring any pattern analysis, the ride simply sucks a lot more as a parking lot coaster than it does as a terrain coaster. On full display out in the open, there’s no longer any sense of mystery and the only surprise remaining is a double-dip set in a small ditch on the return run.

I still retained some hope on the way into the park when I noticed some fresh lumber on the first drop with a dated stamp only a few months old. It was a token prize, but if I couldn’t have my old Zeus back, at least I’d have a coaster that ran fast and smooth. Settled into the rear row, we hurtled down the first 85’ drop effortlessly. Up into the first bunny hill, we caught a magical boost of airtime as we zipped through Hades’ support structure. Hey, the refurbishment seems to be working wonders!

at least I’d have a coaster that ran fast and smooth. Settled into the rear row, we hurtled down the first 85’ drop effortlessly. Up into the first bunny hill, we caught a magical boost of airtime as we zipped through Hades’ support structure. Hey, the refurbishment seems to be working wonders!

Then the wheels made contact with the track bed again, and we quickly – and painfully – discovered it only had a partial refurbishment. I’ve been on some poorly maintained CCI coasters, but I don’t think any had deteriorated as badly as Zeus. For the rest of the layout our internal organs needed defending, which is not logically obvious how to do. Against better judgment we tried it again, where we found that the front row (and only the front row) was still quite smooth and thrilling, while even one or two seats further back were like putting your brain in a paint mixer. Thankfully they are taking some action to repair the track, so maybe once the retracking is complete Zeus will be an enjoyable ride in every seat and not just the very front, but it will never again be the great ride it once was without years of reforestation.

The Dells’ original wooden roller coaster, the 1995 built Cyclops, has aged much better. I’m not sure if it received a retracking project more recently than Zeus, or if the slower average speed and lighter PTCs simply means it doesn’t dig into the track as much. The unrestrictive buzz-bar restraints undoubtedly help our perception of a smooth ride as well, since any jostling absorbed by the cars isn’t then directly transferred into our bodies, as the tighter individual lapbar design tends to do. The ride is legendary for the back-row rides it gives; a legend undoubtedly fueled in part by the eyebrow raising and now infamous “You Must Be 18 or Older to Ride in the Last Car” sign.

The Dells’ original wooden roller coaster, the 1995 built Cyclops, has aged much better. I’m not sure if it received a retracking project more recently than Zeus, or if the slower average speed and lighter PTCs simply means it doesn’t dig into the track as much. The unrestrictive buzz-bar restraints undoubtedly help our perception of a smooth ride as well, since any jostling absorbed by the cars isn’t then directly transferred into our bodies, as the tighter individual lapbar design tends to do. The ride is legendary for the back-row rides it gives; a legend undoubtedly fueled in part by the eyebrow raising and now infamous “You Must Be 18 or Older to Ride in the Last Car” sign. Too bad on our visit the very last row

Too bad on our visit the very last row in the train had its lapbar broken off and was thus out of service. I’m sure there’s a perfectly benign reason for this that fits into Mt. Olympus’ general “we’ll fix it only when we absolutely have to” attitude towards ride maintenance, but it could be fun to believe that this incident fits into the enthusiast mythology surrounding Cyclops’ ejector airtime.

in the train had its lapbar broken off and was thus out of service. I’m sure there’s a perfectly benign reason for this that fits into Mt. Olympus’ general “we’ll fix it only when we absolutely have to” attitude towards ride maintenance, but it could be fun to believe that this incident fits into the enthusiast mythology surrounding Cyclops’ ejector airtime.

When most people talk about Cyclops and its possible justification as a top ten wooden coaster, they talk about the drop. Of course it’s a ride with several drops, but anyone who’s seen it knows instantly which drop we’re talking about. The 75’ midcourse drop off the side of a small hillside in the middle of the park is famous for having some of the strongest sustained negative G-forces of any wooden coaster ever built, intensified by the use of single-position buzz bars on the train that allow for several inches of slack between one’s lap and the restraint.3

negative G-forces of any wooden coaster ever built, intensified by the use of single-position buzz bars on the train that allow for several inches of slack between one’s lap and the restraint.3

However, I’m going to take a couple steps back and argue that what really makes Cyclops succeed is the strong progression of the layout. We must consider the context leading up to the drop that makes it such a psychologically distinctive moment, because if it is only the raw force that matters then Cyclops would not be particularly distinguishable in quality from certain bungee or tower rides that can be commonly found throughout the country. Consider: would the drop be as effective if it was also the layout’s first drop, instead of being positioned near the end?

Whereas Zeus has (had) a balanced and elliptical progression structure that I once might have described as elegant, Cyclops has a very uneven, brash, and dramatic layout progression that’s all about building tension to a singular climatic moment. The coaster starts with a series of small curving drops and hills that wrap under Zeus’ lift. The forces in this section are already pretty strong, with a couple hills that will make your lap connect with the safety bar and some hard laterals around the underbanked swooping curves. The timing between elements is fairly short (corresponding with the small scale of these elements) giving it an “aggressive but playful” personality, like an adolescent dog that hasn’t learned his teeth are sharper and his jaw is stronger than when he was a puppy. We know what this beast is capable of, the question is: does it know?

We know what this beast is capable of, the question is: does it know?

As we start to cross back under the lift, the pacing suddenly slows and the unpredictable forces disappear. There’s an extended moment of silence as we round a couple of flat curves and shallow upward climbs. Instead of the small scale, lumber and tree dodging first act, the vista opens up to a wide panoramic high over the rest of the park. We become palpably anxious, not just because there’s violent force approaching, but because we’ve internalized the knowledge that violent force is approaching and yet we’re experiencing a moment of relative calm and serenity. The drop is not just an act of violence; it’s a premeditated act of violence.

I do not use the word “violence” metaphorically. I think all roller coasters can be considered “violent” in a very real and tangible way (and not just the uncomfortably rough ones like Zeus). This might sound odd because we consider them voluntary and purposely for fun, but the structure of our experience of a roller coaster is more or less the same as any other experience of violence. It is force exerting power over the human body. That’s pretty much the shared definition of violence and roller coaster experiences.4 It’s only the fact that we still retain some control and autonomy over our bodies (even if we momentarily surrender that control to the coaster, it was our choice to be here in the first place and we feel assured nothing permanently bad will happen to us) that makes this violence entertaining; similar in nature to how good jokes

I do not use the word “violence” metaphorically. I think all roller coasters can be considered “violent” in a very real and tangible way (and not just the uncomfortably rough ones like Zeus). This might sound odd because we consider them voluntary and purposely for fun, but the structure of our experience of a roller coaster is more or less the same as any other experience of violence. It is force exerting power over the human body. That’s pretty much the shared definition of violence and roller coaster experiences.4 It’s only the fact that we still retain some control and autonomy over our bodies (even if we momentarily surrender that control to the coaster, it was our choice to be here in the first place and we feel assured nothing permanently bad will happen to us) that makes this violence entertaining; similar in nature to how good jokes about the tragic reality of the world can also be some of the funniest.

about the tragic reality of the world can also be some of the funniest.

If the progression of Cyclops can be characterized as slowly teasing out psychological tension through a combination of two methods in the opening act, and then pulls the floor out from under us (literally and figuratively) at the start of the second, we might wonder how the final couple of curves fit into the layout’s narrative structure beyond simply functioning as a way to get us back to the station after the climax. I think this is a case where declining action and denouement serves a very important purpose for coaster narratology. If the ride simply ended at the bottom of the drop, it would feel incomplete and our bodies would be burning with a sudden shot of adrenaline and no place to expend it. These curves, technically the fastest part of the ride, are visceral without being forceful (although a banked hill between the two right hand curves creates some odd sensations), and the high speeds are a satisfactory conclusion to the slow build-up of tension in the first act without becoming too much for us physically. The layout still feels a bit too short and incomplete regardless (the progression is extremely compact, with each “act” lasting no longer

after the climax. I think this is a case where declining action and denouement serves a very important purpose for coaster narratology. If the ride simply ended at the bottom of the drop, it would feel incomplete and our bodies would be burning with a sudden shot of adrenaline and no place to expend it. These curves, technically the fastest part of the ride, are visceral without being forceful (although a banked hill between the two right hand curves creates some odd sensations), and the high speeds are a satisfactory conclusion to the slow build-up of tension in the first act without becoming too much for us physically. The layout still feels a bit too short and incomplete regardless (the progression is extremely compact, with each “act” lasting no longer than ten to fifteen seconds), but by the end of the ride there’s no mistaking that it makes the most out of every foot of its 1900 feet of track.

than ten to fifteen seconds), but by the end of the ride there’s no mistaking that it makes the most out of every foot of its 1900 feet of track.

If Cyclops is an exemplar of how to efficiently establish dramatic progression in a coaster layout, then Pegasus might seem to be an example of how coaster layouts can just kind of randomly dick around until it’s over. The family coaster, opened in 1996 and positioned near the front of the park along the Wisconsin Dells Parkway and over several go-kart tracks, can be tough to describe. The first drop is only about two-thirds the height of the lift, and then it goes into a long elevated section of apparently arbitrary dips and box curves taken at less than 20mph. It’s not until the return run when it drops most of the way to ground level, and then finishes with a couple of hills that fail to provide anything resembling airtime. Capping it all off, just before the brakes there’s a little right-hand shimmy that, depending on how the guide wheels catch it (there’s always a bit of slack that results in the typical wooden coaster feel), can significantly rattle the front car

Wisconsin Dells Parkway and over several go-kart tracks, can be tough to describe. The first drop is only about two-thirds the height of the lift, and then it goes into a long elevated section of apparently arbitrary dips and box curves taken at less than 20mph. It’s not until the return run when it drops most of the way to ground level, and then finishes with a couple of hills that fail to provide anything resembling airtime. Capping it all off, just before the brakes there’s a little right-hand shimmy that, depending on how the guide wheels catch it (there’s always a bit of slack that results in the typical wooden coaster feel), can significantly rattle the front car or glide through as if it wasn’t even there. Even having ridden it several times I still can’t quite trace the layout in my mind despite the fact that it’s composed of very simple elements and takes about thirty-five seconds to complete from top of the lift to the brakes.

or glide through as if it wasn’t even there. Even having ridden it several times I still can’t quite trace the layout in my mind despite the fact that it’s composed of very simple elements and takes about thirty-five seconds to complete from top of the lift to the brakes.

Nevertheless I now think there’s a bit more purpose to the layout beyond just randomly wandering over the nearby go-kart tracks. There are two distinct flavors to the experience: the faster, hilly sections at the beginning and end, and the slower elevated section with box turns and little dips. And that elevated section even kind of resembles the sensation of a horse galloping through the air. It seems entirely possible that might have been an intentional design feature inspired by the coaster’s proposed name; although even if true, who knows if I might have been the first customer to have ever consciously made that association? Worse, some of that purpose of the elevated layout is missing now that the Medusa Drop Track is removed and part of the ride is just circling over an empty grass lot.

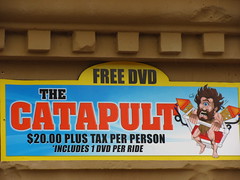

Yes, I was surprised to find that instead of expanding the park to match the extra capacity suggested by the parking lot, they’ve spent money to whittle it down. There are fewer worthwhile attractions at Mt. Olympus than there was when the Parthenon was built in 2006. The Medusa’s Drop Track, the famous airtime filled go-karts; Dive to Atlantis, the admittedly kind of lousy watercoaster; the Zamperla Disk’O, the park’s only adult flat ride included with admission… all of these are gone without replacement. The only things that have been added are a small Zamperla children’s ride package in part of the area once covered by Medusa’s Drop, and several upcharge attractions that are essentially expensive lawn ornaments, as no one was willing to pay $15 to $20 (plus tax) for a two minute ride. Once famed for their diverse collection of 16 go-kart tracks,

Yes, I was surprised to find that instead of expanding the park to match the extra capacity suggested by the parking lot, they’ve spent money to whittle it down. There are fewer worthwhile attractions at Mt. Olympus than there was when the Parthenon was built in 2006. The Medusa’s Drop Track, the famous airtime filled go-karts; Dive to Atlantis, the admittedly kind of lousy watercoaster; the Zamperla Disk’O, the park’s only adult flat ride included with admission… all of these are gone without replacement. The only things that have been added are a small Zamperla children’s ride package in part of the area once covered by Medusa’s Drop, and several upcharge attractions that are essentially expensive lawn ornaments, as no one was willing to pay $15 to $20 (plus tax) for a two minute ride. Once famed for their diverse collection of 16 go-kart tracks, only five adult tracks remain, two of which were closed for no apparent reason. The Helios and Poseidon tracks were both deserted for the entire length of our visit; did all the individual go-karts break down at once, I wonder? I can’t speculate if the closure of certain tracks is the exception or the norm.

only five adult tracks remain, two of which were closed for no apparent reason. The Helios and Poseidon tracks were both deserted for the entire length of our visit; did all the individual go-karts break down at once, I wonder? I can’t speculate if the closure of certain tracks is the exception or the norm.

This left us with a meager three go-kart tracks we could try. The biggest and best was quite handily the Trojan Horse Track, with its huge multi-level helices that lead three stories up to the belly of a Trojan horse replica. It could have been a great racetrack as well, if only we had halfway decent cars to race with. As I recall this has been a problem since the days of Big Chief’s Carts and Coasters; they use a standardized fleet of small, black plastic exterior vehicles that I’m guessing must have been selected for their cheapness and interchangeability rather than for any certification of quality.

black plastic exterior vehicles that I’m guessing must have been selected for their cheapness and interchangeability rather than for any certification of quality.

The biggest problem is that they’re slow, making it almost impossible to get exciting races going. Pretty much as soon as you take off you can press the gas pedal all the way to the floor, and you’ll never need to lift off for the entire race unless you’re somehow forcing an extreme hairpin turn. The winner, therefore, is usually decided either by who gets a cart at the front of the station, or who gets a cart that’s recently been refurbished and runs a hair faster than all the others. The ergonomics aren’t great either, and I don’t think these carts are equipped with shock absorbers intended for the elevated wood plank tracks. They vibrate so much that my butt and back would go partially numb by the end of the race, and it makes maneuvering with the steering wheel a helluva lot more difficult than it should be. Although there was one occasion when I drove over a small puddle of water that had collected at the top of the Trojan Horse Track, which caused my poor, underperforming vehicle to suddenly loose all traction and crash into the nearest carts and barriers, continuing to fishtail wildly around the first part of the descending helix… and all the while as I tried to get it under control I still kept my foot flat down on the gas pedal! And that honestly was some of the most fun and excitement I’ve ever had on go-karts.

that my butt and back would go partially numb by the end of the race, and it makes maneuvering with the steering wheel a helluva lot more difficult than it should be. Although there was one occasion when I drove over a small puddle of water that had collected at the top of the Trojan Horse Track, which caused my poor, underperforming vehicle to suddenly loose all traction and crash into the nearest carts and barriers, continuing to fishtail wildly around the first part of the descending helix… and all the while as I tried to get it under control I still kept my foot flat down on the gas pedal! And that honestly was some of the most fun and excitement I’ve ever had on go-karts.

The Titan’s Tower track, despite its name, remains close to the ground for most of the layout with a couple of small figure eights thrown in underneath the Pegasus structure. Supposedly this is the longest track in the park, although I can’t imagine it’s much longer than the Trojan Horse or Poseidon tracks and it’s certainly not as memorable except for a few points along the track where a small sharp ledge in the transition between pavements and

of small figure eights thrown in underneath the Pegasus structure. Supposedly this is the longest track in the park, although I can’t imagine it’s much longer than the Trojan Horse or Poseidon tracks and it’s certainly not as memorable except for a few points along the track where a small sharp ledge in the transition between pavements and elevated track convinced me I was going to blow a tire and dent the undercarriage. The last adult-sized track was Hermes’ Turbo Track. This one was advertised as being the park’s “speed track”, but as it uses the exact same carts as the others (possibly tuned to go a few mph faster) I wouldn’t go far out of my way for it. Nevertheless, replacing the wooden plank track with a series of sweeping ground-level s-curves made it much more comfortable and even allowed for a bit of racing, not that it was anything you couldn’t find in an average FEC. Not having to pay an upcharge continues to be the most welcomed feature of the remaining tracks at Mt. Olympus (I rarely do go-karts anymore mostly for that reason, they’re just not worth the upcharge), but they would need to upgrade their fleet of cars before I’d consider returning to the Dells just to ride the go-karts.

elevated track convinced me I was going to blow a tire and dent the undercarriage. The last adult-sized track was Hermes’ Turbo Track. This one was advertised as being the park’s “speed track”, but as it uses the exact same carts as the others (possibly tuned to go a few mph faster) I wouldn’t go far out of my way for it. Nevertheless, replacing the wooden plank track with a series of sweeping ground-level s-curves made it much more comfortable and even allowed for a bit of racing, not that it was anything you couldn’t find in an average FEC. Not having to pay an upcharge continues to be the most welcomed feature of the remaining tracks at Mt. Olympus (I rarely do go-karts anymore mostly for that reason, they’re just not worth the upcharge), but they would need to upgrade their fleet of cars before I’d consider returning to the Dells just to ride the go-karts.

But, no. Instead of spending capital investments to improve or build new attractions, one of the major cash projects from the last couple years was to arbitrarily relocate the main ticket booths by several hundred yards. While the original location near Cyclops’ big drop was maybe a bit awkwardly integrated with the rest of the park, the current entrance on the far side of Hades’ drop is quite baffling. On the immediate opposite side of the ticket gates you run into a chain link fence protecting Zeus’ out run. To get into the park you have to turn left and take a narrow pathway under Hades’ drop, through a gift shop squeezed inside Zeus’ lift supports, and then wind between Cyclops and Zeus’ structures to reach what used to be the far back of the park connecting the wooden coasters. There’s not a tremendous amount of protection from the coaster structures which lets you get very close to the onrushing trains, which I sort of liked as a coaster geek and photographer. But I can’t imagine the logistical thinking that went into making the entrance thoroughfare such an awkward and unintuitive design, and would fear this pathway at the beginning or end of a busy summer day.

There’s not a tremendous amount of protection from the coaster structures which lets you get very close to the onrushing trains, which I sort of liked as a coaster geek and photographer. But I can’t imagine the logistical thinking that went into making the entrance thoroughfare such an awkward and unintuitive design, and would fear this pathway at the beginning or end of a busy summer day.

The rest of the infrastructure continues to be a bit of a mess, probably partly a result of a long history of merging and combining different resorts and attractions into one. While we never used it, the indoor/outdoor water park in particular seems to suffer from a scattered, illogical placement. Walking from one end of the property to the other can be extremely tiring, yet despite the labyrinthine abundance of pathways there’s a conspicuous lack of attractions they lead to. Thankfully the major coasters are all clustered together, although even within this small area I’d sometimes get turned around, not sure which forks led to the queues and which to the ride exits, the park exit, or various service and maintenance roads. Guide maps, as well as fences, lamp posts, and other common midway ornamentations are a rarity along these walkways, but there’s no shortage of loudspeakers blaring an endless loop of pop and hip-hop songs everywhere except the most remote corners of the park. While themed styrofoam has been scattered throughout the park, a lot of shade trees have been removed which can make a summer day quite brutal.

yet despite the labyrinthine abundance of pathways there’s a conspicuous lack of attractions they lead to. Thankfully the major coasters are all clustered together, although even within this small area I’d sometimes get turned around, not sure which forks led to the queues and which to the ride exits, the park exit, or various service and maintenance roads. Guide maps, as well as fences, lamp posts, and other common midway ornamentations are a rarity along these walkways, but there’s no shortage of loudspeakers blaring an endless loop of pop and hip-hop songs everywhere except the most remote corners of the park. While themed styrofoam has been scattered throughout the park, a lot of shade trees have been removed which can make a summer day quite brutal.

The Parthenon is one escape from the weather (in our case, light rain showers instead of oppressive sun) although after more than twenty minutes it might begin to feel more like an imprisonment than a retreat. The exterior had a very impressive (and very styrofoam) colonnade adorning the front which seemed to promise greatness (or at least, not mediocrity) inside. However, the actual structure behind this façade is basically just a gigantic beige tent. Inside, it is filled with a collection of mostly Zamperla children’s rides, none of which are even remotely themed to Ancient Greece, and a Zamperla spinning wild mouse coaster called Opa!. An almost-attempt at a custom theme, apart from the name this ride still retains its carny colors and whacked-out rainbow mouse vehicles. It was still decent fun for a couple of laps,

The Parthenon is one escape from the weather (in our case, light rain showers instead of oppressive sun) although after more than twenty minutes it might begin to feel more like an imprisonment than a retreat. The exterior had a very impressive (and very styrofoam) colonnade adorning the front which seemed to promise greatness (or at least, not mediocrity) inside. However, the actual structure behind this façade is basically just a gigantic beige tent. Inside, it is filled with a collection of mostly Zamperla children’s rides, none of which are even remotely themed to Ancient Greece, and a Zamperla spinning wild mouse coaster called Opa!. An almost-attempt at a custom theme, apart from the name this ride still retains its carny colors and whacked-out rainbow mouse vehicles. It was still decent fun for a couple of laps, in part because as the only semi-major steel coaster in the Wisconsin Dells

in part because as the only semi-major steel coaster in the Wisconsin Dells it didn’t try to rattle more of our brain cells out of our ears, and because if you pile your party into the right-hand side you can get some really good spinning in the second half. But after two or three laps we had run out of activities to do inside and, in the absence of natural light and with the fumes and noises of the kiddie go-karts trapped inside the tent, we became quickly anxious for the rain to stop enough that we could continue riding the wooden coasters. As previously noted, the Zamperla Disk’O once featured as the secondary adult ride in the Parthenon has been inexplicably banished, which left the biggest additional amusement found inside for us to be a vending machine selling exclusively socks.

it didn’t try to rattle more of our brain cells out of our ears, and because if you pile your party into the right-hand side you can get some really good spinning in the second half. But after two or three laps we had run out of activities to do inside and, in the absence of natural light and with the fumes and noises of the kiddie go-karts trapped inside the tent, we became quickly anxious for the rain to stop enough that we could continue riding the wooden coasters. As previously noted, the Zamperla Disk’O once featured as the secondary adult ride in the Parthenon has been inexplicably banished, which left the biggest additional amusement found inside for us to be a vending machine selling exclusively socks.

If there’s only one thing that Mt. Olympus has figured out how to do really well, it’s how to make deals. Once you’re on their property, there’s a ceaseless stream of offers and promotions that try to get you to shell out just a little bit more.

If there’s only one thing that Mt. Olympus has figured out how to do really well, it’s how to make deals. Once you’re on their property, there’s a ceaseless stream of offers and promotions that try to get you to shell out just a little bit more.

It’s when you first arrive: pay a $5.00 parking fee to cover the parking fee attendant’s wage and the cost of building several acres of unused overflow parking lots, although if you have the right ticket receipt then it doesn’t matter.

It’s at the admission booth: Night at the Theme Park is $22.00 for three hours of time in the park, which is only $3.00 less than a normal park admission ticket valid from 10:00am to 9:00pm. But if you buy a one-day ticket, then the value of Night at the Theme Park is magically reduced to only $5.00.

But if you buy a one-day ticket, then the value of Night at the Theme Park is magically reduced to only $5.00.

It’s on the rides: $15 to $20 to have the ride operator to take two minutes of their time to strap you into a swing or catapult and press the dispatch button, but a physical commodity in the form of an on-ride DVD is complementary.

It’s in the gift shops and game booths: buy one for $7.00 or buy two for $10.00! Play twice at an exorbitant price, get the third game free! Trigger random discounts of up to 90% for doing nothing but spend money in the right places!

Even when you book your hotel: a family of four can pay $150 for one day of water and theme park admission and no hotels, or they can pay $100 for on-site accommodations and get two days of unlimited park admissions (a $300 value) for nothing at all!

Even when you book your hotel: a family of four can pay $150 for one day of water and theme park admission and no hotels, or they can pay $100 for on-site accommodations and get two days of unlimited park admissions (a $300 value) for nothing at all!

Some of these practices may lead you to feel you’re being nickeled-and-dimed, others may make you to believe you’ve just made the steal of a lifetime. But what they all have in common is that arbitrarily inconsistent pricing destroys a customer’s perceptions of the value of a dollar. We are told over and over again that nothing Mt. Olympus is selling has any intrinsic or fixed worth. We know it costs money to run the place, but nothing we spend is actually pegged to that commodity’s marginal value; the contents of our wallet are emptied into the mysterious money pile in the sky, and then by incident Mt. Olympus decides what we get for our donations. Ultimately this practice only leads to a competitive relationship between the park and its guests, and it results in reduced spending overall. Aware of all the little extras I could buy or receive and their relative (un)worth to everything else I had already spent money on, I felt the constant need to guard my wallet and calculate the real cost-benefit of every penny I put down that Mt. Olympus was intent to deceive me of its actual value. Yet at the end of the trip when I finally sat down to count out what had been spent on what, I found that with the various hotel deals and so on I had actually spent less than I probably would have at a “normally priced” regional amusement park.5

or receive and their relative (un)worth to everything else I had already spent money on, I felt the constant need to guard my wallet and calculate the real cost-benefit of every penny I put down that Mt. Olympus was intent to deceive me of its actual value. Yet at the end of the trip when I finally sat down to count out what had been spent on what, I found that with the various hotel deals and so on I had actually spent less than I probably would have at a “normally priced” regional amusement park.5

To summarize: I think Mt. Olympus has made some poor managerial decisions uncharacteristic of most “family owned and operated” businesses, and I’m not sure I like the trend I’m seeing for the future of the park. For a place that has so much potential (or, at least, had the potential several years ago), they’ve shown a knack for chasing after some of the wrong investments and putting customer satisfaction inside their core theme park business at a lower priority to other non-value-added interests, like buying out pre-existing local hotels or holding a personal grudge against the nearby trees.

Perhaps it’s just the rampant, superficial commercialism of the Dells that’s toxified the air and water Mt. Olympus uses. But there’s something a little despicable, maybe even pathological, about a business that’s willing to destroy huge quantities of trees to boost the theoretical number of customers they can shove through the gates without ever spending a dime to increase capacity or improve guest experience once they’ve paid for their tickets, all the while openly and notoriously showing interest in easy profits and gimmicks before demonstrating any pride in running a respectable, fair business that treats all of their customers as if they’re actually intelligent human beings.6

There’s one last fallen angel to be found in the park, and it is called Hades. When it opened in 2005 it created a furor, once the Gravity Group’s very first roller coaster seemed to exceed the scale and ambition of nearly anything previously produced by Custom Coasters International or Great Coasters International in all their prior years of business. With the world’s longest underground tunnel on a roller coaster as well as the first ever 90° banked turn on wooden coaster, the future looked bright for the Gravity Group.

There’s one last fallen angel to be found in the park, and it is called Hades. When it opened in 2005 it created a furor, once the Gravity Group’s very first roller coaster seemed to exceed the scale and ambition of nearly anything previously produced by Custom Coasters International or Great Coasters International in all their prior years of business. With the world’s longest underground tunnel on a roller coaster as well as the first ever 90° banked turn on wooden coaster, the future looked bright for the Gravity Group.

Yet the future for Hades, in spite of its powerful and innovative layout, was perhaps destined for eventual mediocrity from the very start, given who would be tasked with upkeep of the ride. A single 5-car train operation was suspicious from the very moment it started making test runs. That’s the sort of capacity that’s okay for a short, mid-sized wooden coaster at a rural go-kart park in 1995, not a nearly mile long headlining monster at a rapidly growing regional theme park in 2005. Still, if you could put up with the long lines or visit on a lightly attended day, the ride that awaited you that initial year was nothing short of world-class. Today, its status as the best of the best is less certain. Like Zeus, the wooden track has taken a bit of a beating from the PTC trains. The front row is still smooth, but the other cars (especially in the rear wheel seats) can pick up a vibration that is at best distracting and at worst painful.

the very moment it started making test runs. That’s the sort of capacity that’s okay for a short, mid-sized wooden coaster at a rural go-kart park in 1995, not a nearly mile long headlining monster at a rapidly growing regional theme park in 2005. Still, if you could put up with the long lines or visit on a lightly attended day, the ride that awaited you that initial year was nothing short of world-class. Today, its status as the best of the best is less certain. Like Zeus, the wooden track has taken a bit of a beating from the PTC trains. The front row is still smooth, but the other cars (especially in the rear wheel seats) can pick up a vibration that is at best distracting and at worst painful.

Also, while expanding the ride’s capacity is out of the cards for Mt. Olympus (not even the addition of a sixth car even though the station is already equipped with the gates for one) they did take it upon themselves to add these weird high walls to the inside of the coaster seats. I’m guessing they must have had an incident with someone sticking their hands out of the car and are there to protect the stupid people from themselves, but for everyone else with even a moderate body build we’re forced to keep knocking shoulders with our riding partner and the wall padding throughout the ride. It’s still possible to get some really good front row night rides on Hades, but Mt. Olympus does what it can to make that as difficult as possible. Who knows what they’ll come up with in a few more years?

the station is already equipped with the gates for one) they did take it upon themselves to add these weird high walls to the inside of the coaster seats. I’m guessing they must have had an incident with someone sticking their hands out of the car and are there to protect the stupid people from themselves, but for everyone else with even a moderate body build we’re forced to keep knocking shoulders with our riding partner and the wall padding throughout the ride. It’s still possible to get some really good front row night rides on Hades, but Mt. Olympus does what it can to make that as difficult as possible. Who knows what they’ll come up with in a few more years?

Although the layout lacks the elegantly elliptical or dramatically climatic progression of its smaller predecessors, there is still something unique about the ride’s narrative that’s worth noting. While most good roller coasters progress from large, fast elements with drawn-out forces to smaller, fleeter maneuvers with rapid bursts of force and direction changes (mostly necessitated by the loss of speed from friction), Hades turns this ‘standard’ progression on its head.

or dramatically climatic progression of its smaller predecessors, there is still something unique about the ride’s narrative that’s worth noting. While most good roller coasters progress from large, fast elements with drawn-out forces to smaller, fleeter maneuvers with rapid bursts of force and direction changes (mostly necessitated by the loss of speed from friction), Hades turns this ‘standard’ progression on its head. It places the sharp pops of airtime

It places the sharp pops of airtime and laterals with fast transitions at the very beginning, thanks to the elevated station and pre-lift section. The section after the main drop is more typical of a midcourse progression, with agile bunny hops in the tunnels and a slow pause at the top of the far turn around. It isn’t until the end of the ride when the coaster opens up to viscerally high speeds and drawn out element timing, rampaging through the woods (what’s left of them) over wide, steeply banked curves and shallow drops, crashing into the brakes with plenty of fury to spare. Subtle but unique, it’s a progression that can’t quite be boxed in using any simple linear or circular pattern analyses. Hades is a roller coaster that has an epic story to tell, and there are developments, lulls,

and laterals with fast transitions at the very beginning, thanks to the elevated station and pre-lift section. The section after the main drop is more typical of a midcourse progression, with agile bunny hops in the tunnels and a slow pause at the top of the far turn around. It isn’t until the end of the ride when the coaster opens up to viscerally high speeds and drawn out element timing, rampaging through the woods (what’s left of them) over wide, steeply banked curves and shallow drops, crashing into the brakes with plenty of fury to spare. Subtle but unique, it’s a progression that can’t quite be boxed in using any simple linear or circular pattern analyses. Hades is a roller coaster that has an epic story to tell, and there are developments, lulls, and climatic action sequences that all fit together into an extremely satisfying narrative arc.

and climatic action sequences that all fit together into an extremely satisfying narrative arc.

Nevertheless, the highlight of the Hades is ironically when it’s at its lowest and darkest, found inside the double underground tunnel that spans the length of Mt. Olympus’ formidable parking lot. This is an incredible piece of engineering by the Gravity Group in the way that it completely engulfs you and, even at high speeds, holds you in the dark for longer than seems natural. The only downside is that it completely upstages the other big record breaking feature, the 90° banked turn that’s found along the first leg of the tunnel.

the length of Mt. Olympus’ formidable parking lot. This is an incredible piece of engineering by the Gravity Group in the way that it completely engulfs you and, even at high speeds, holds you in the dark for longer than seems natural. The only downside is that it completely upstages the other big record breaking feature, the 90° banked turn that’s found along the first leg of the tunnel.

Perhaps they were a little too eager to demonstrate their mastery of physics and advanced track calculus, but the extreme banked turn is maneuvered too perfectly. We can’t feel anything in the way of unexpected or even expected forces along this turn, and since we obviously can’t see anything, probably 95% of riders come back to the station not even aware that at one point underground they were turned completely on their sides. This was a big problem in its opening year; it was virtually indistinguishable from a flat stretch of track. However, now that the track has degraded somewhat and the precision engineering has more interference with the wheels jostling around, I could kind of make sense that something felt askew during that turn. I actually like the return leg inside the tunnel better. It doesn’t matter that we’re not going as fast on the way back because we don’t have any points of reference to judge our speed, so the darkness lasts longer. And as soon as you can see the light at the end of the tunnel, the designers throw a curveball at us and send us over a slightly reverse-banked curved bunny hop;

Perhaps they were a little too eager to demonstrate their mastery of physics and advanced track calculus, but the extreme banked turn is maneuvered too perfectly. We can’t feel anything in the way of unexpected or even expected forces along this turn, and since we obviously can’t see anything, probably 95% of riders come back to the station not even aware that at one point underground they were turned completely on their sides. This was a big problem in its opening year; it was virtually indistinguishable from a flat stretch of track. However, now that the track has degraded somewhat and the precision engineering has more interference with the wheels jostling around, I could kind of make sense that something felt askew during that turn. I actually like the return leg inside the tunnel better. It doesn’t matter that we’re not going as fast on the way back because we don’t have any points of reference to judge our speed, so the darkness lasts longer. And as soon as you can see the light at the end of the tunnel, the designers throw a curveball at us and send us over a slightly reverse-banked curved bunny hop; this is a trick we can feel and see.

this is a trick we can feel and see.

More than the placement of 90° banking underground, the biggest drawback of Hades’ layout is that a few of the hills feel like they were designed expecting that the train would retain more speed than it actually does. The big steep incline after the first tunnel is particularly problematic in this regard, as the train usually feels like it’s going to stall out on this part (and it sometimes randomly does). That’s not a huge loss since it works well as a contemplative pause in the middle of the underground madness, but the camelback hill that runs parallel to the lift after the second tunnel always seems to underdeliver on a promise of big airtime, and I don’t see any way to justify that. The only decent negative G-forces along the layout that are not underground are on the speed hill before the second tunnel and a few of the sharp bunny hops on the pre-lift section (including the drop out of the station if you’re in the last row).

are on the speed hill before the second tunnel and a few of the sharp bunny hops on the pre-lift section (including the drop out of the station if you’re in the last row). Underground there are a ton of pops of airtime mixed with a few laterals (except for where 90° banked track is involved), which helps solidify those tunnels as the reason to make Mt. Olympus a coaster enthusiast’s destination.

Underground there are a ton of pops of airtime mixed with a few laterals (except for where 90° banked track is involved), which helps solidify those tunnels as the reason to make Mt. Olympus a coaster enthusiast’s destination.

I’m at the point where trying to describe the ways in which Hades is a very good coaster seems pointless. Watch a video of the ride and you’ll understand (with apologies to Michael Mann) that I don’t have to sell you this shit and you know it, because this kind of shit here sells itself. What I would like to do is propose constructively how Mt. Olympus management can once again appear as an agent for improving the park instead of conspiring against it as the past couple years have suggested.

I’m at the point where trying to describe the ways in which Hades is a very good coaster seems pointless. Watch a video of the ride and you’ll understand (with apologies to Michael Mann) that I don’t have to sell you this shit and you know it, because this kind of shit here sells itself. What I would like to do is propose constructively how Mt. Olympus management can once again appear as an agent for improving the park instead of conspiring against it as the past couple years have suggested.

Here’s what I would do for Hades: call in the Gravity Group to do major rehab on Hades (but after they fix Zeus so it doesn’t cause any lawsuits, of course). Aside from retracking, completely rebuild the final helix and lower the brake run down to station level. This would eliminate the dip into the station and allow for enough extra safety braking room to accommodate a second train and a transfer track. Replace the existing train with two 24-passenger Timberliners; one burgundy and one charcoal black. I’ve also always wanted a bigger finish to Hades. The upward spiral starts strong but it loses too much speed so it finishes on a dull note. Lowering the brake would give it more speed at the finish, and I would also propose that while this area is being reconstructed, to add a second layer to the track so it has a strong double helix finale similar to the Beast or Shivering Timbers. (With two trains the ride can last a little longer without sacrificing capacity.)

to do major rehab on Hades (but after they fix Zeus so it doesn’t cause any lawsuits, of course). Aside from retracking, completely rebuild the final helix and lower the brake run down to station level. This would eliminate the dip into the station and allow for enough extra safety braking room to accommodate a second train and a transfer track. Replace the existing train with two 24-passenger Timberliners; one burgundy and one charcoal black. I’ve also always wanted a bigger finish to Hades. The upward spiral starts strong but it loses too much speed so it finishes on a dull note. Lowering the brake would give it more speed at the finish, and I would also propose that while this area is being reconstructed, to add a second layer to the track so it has a strong double helix finale similar to the Beast or Shivering Timbers. (With two trains the ride can last a little longer without sacrificing capacity.)

Then, take Hades’ current five-car PTC train and put it on Zeus. Maybe do a similar reprofiling and transfer track addition so it can run two trains, or at the very least put one of the new cars onto the existing train so it can run with six cars (I think the Zeus station was also originally designed for six). Maybe another donor car can go to Pegasus, since one four-car train is also a bit short on capacity on days that are able to fill the entire parking lot. Cyclops can stay the way it is as long as it receives the required amount of TLC, since it’s a short layout that’s easy to load and dispatch quickly with the buzzbars. By the way, I’d like to see some of the parking lot around Zeus bulldozed and replanted with trees, but that’s probably wishful thinking.

and replanted with trees, but that’s probably wishful thinking.

While we’re in Fantasyland, I’d also like it if the Medusa Drop Track could be resurrected from the dead, and if the go-karts could all be upgraded to a faster design with better shock absorbers, and if the convoluted path infrastructure could be consolidated into one easy to follow central midway with a direct route to the main entrance, and place thematically consistent non-up-charge flat rides and secondary attractions in the new space that will free up, and if they could get a more competitive, professional HR department, and if only I could crap thunder and piss lightning… but, let’s be realistic, none of that will happen until the day Hades’ realm freezes over.

Then again, Wisconsin does get pretty cold in the winter, and I can’t imagine that asphalt parking lot doesn’t occasionally form a thick layer of ice…

Comments