Valencia, California_________________________

After two full days of light crowds and unlimited roller coasters, I concluded that my time at Magic Mountain had gone far better than I would have set even my highest expectations. This mostly was accounted by the fair California weather that contrasted heavily with the snow and ice I left behind only three days prior, and being granted the freedom to ride whatever I wanted whenever I wanted without needing to plonk down $100 on a Flash Pass. I suspect if the crowds or climes were less ideal (apparently Magic Mountain was coated with snow only a few weeks prior to my arrival) this story could have had a very different tone. But I was lucky, and if there is a moral in all of it, it’s that Magic Mountain in the off-season has the potential to be quite satisfying for the lonely coaster geek.

this story could have had a very different tone. But I was lucky, and if there is a moral in all of it, it’s that Magic Mountain in the off-season has the potential to be quite satisfying for the lonely coaster geek.

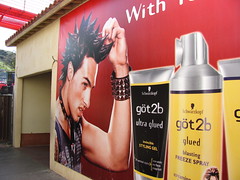

As a park it’s still very much flawed. Efficiency is not ideal in many of the coaster operations, parts of the park are rather derelict and run-down, and beyond the eighteen roller coasters there are extremely few additional attractions of interest; between two days I rode exactly one (1) non-roller coaster ride. I hear the two log flumes are nice and you can even find a couple of flat rides if you squint really hard, but apart from the children’s areas (which included the Canyon Blaster, coaster #417 for me) there’s virtually no divertissement that’s not gravity-based. (Oh, there are also these gawdawful “coaster wrap” advertisements that have raised the ire of more than one enthusiast. The full banner ads festooned in the Viper station and all over one of the operating trains… for a hair product featuring a dood with a look on his face that says “uh oh, this junk is going to be harder to wash out than a bucket of Sherwin Williams”… was all much too much. Mercifully Viper was the only casualty.)

children’s areas (which included the Canyon Blaster, coaster #417 for me) there’s virtually no divertissement that’s not gravity-based. (Oh, there are also these gawdawful “coaster wrap” advertisements that have raised the ire of more than one enthusiast. The full banner ads festooned in the Viper station and all over one of the operating trains… for a hair product featuring a dood with a look on his face that says “uh oh, this junk is going to be harder to wash out than a bucket of Sherwin Williams”… was all much too much. Mercifully Viper was the only casualty.)

The reason I could tell that Magic Mountain is a park on the rise was by looking at what they did to the 384’ Sky Tower. No, it’s not that they finally resuscitated a park landmark that had been shuttered for over half a decade. It’s not that they took the time and effort to install Magic of the Mountain, a museum of park history on the observation deck… or even that management was receptive enough to take the idea from an employee’s suggestion. It’s the evidence that Six Flags feels comfortable enough with the quality of their product that they can risk to evoke present day comparison against rose-tinted nostalgia. Ten years ago such a museum might have been downright depressing; the carefree times of the fuzzy trolls and Revolution movie cameos contrasted with the cold reality of retina-frying parking lot coasters with three hours worth of hooligans standing in front… particularly embarrassing as the place was known in its nostalgia-saturated early years as “Tragic Mountain”. Upon stepping out of the claustrophobic, slightly vertigo-inducing elevator, the sights on display make this observation deck part satellite and part time machine. Well worth a trip up there, even if you didn’t bring your camera.

The reason I could tell that Magic Mountain is a park on the rise was by looking at what they did to the 384’ Sky Tower. No, it’s not that they finally resuscitated a park landmark that had been shuttered for over half a decade. It’s not that they took the time and effort to install Magic of the Mountain, a museum of park history on the observation deck… or even that management was receptive enough to take the idea from an employee’s suggestion. It’s the evidence that Six Flags feels comfortable enough with the quality of their product that they can risk to evoke present day comparison against rose-tinted nostalgia. Ten years ago such a museum might have been downright depressing; the carefree times of the fuzzy trolls and Revolution movie cameos contrasted with the cold reality of retina-frying parking lot coasters with three hours worth of hooligans standing in front… particularly embarrassing as the place was known in its nostalgia-saturated early years as “Tragic Mountain”. Upon stepping out of the claustrophobic, slightly vertigo-inducing elevator, the sights on display make this observation deck part satellite and part time machine. Well worth a trip up there, even if you didn’t bring your camera.

As a roller coaster reviewer, Revolution leaves me facing a paradox. One that catches me in the conflict between evaluating a ride based on the fundamental constitutive properties or on accidental one-time experience, between intent and results, between the universal and the specific. One that makes me glad I don’t give numeric scores and instead just focus on providing a written analysis that allows for dialogue between viewpoints.

As a roller coaster reviewer, Revolution leaves me facing a paradox. One that catches me in the conflict between evaluating a ride based on the fundamental constitutive properties or on accidental one-time experience, between intent and results, between the universal and the specific. One that makes me glad I don’t give numeric scores and instead just focus on providing a written analysis that allows for dialogue between viewpoints.

I happen to really love Revolution. That’s doubtlessly owing to my well-documented affinity for classic parks and attractions, and here is a classic attraction that was a real revolutionary in its time, being the first modern vertical looping roller coaster in 1976.

I love the California Mission architecture of the station, the way you enter under and then cross over the beige stucco arch bearing the ride’s emblem.

I love the California Mission architecture of the station, the way you enter under and then cross over the beige stucco arch bearing the ride’s emblem.

I love the retro-streamlined look of the cars, especially the newly redecorated stars and stripes train that was regrettably out of service on my visit.

I love the simple but elegant craftsmanship that Schwarzkopf and Intamin used to construct it, the way the minimalist white track and supports disappears into the trees, and not reappearing again until it arrives at the singular, iconic vertical loop staged front and center over Valencia Falls.

I love the use of terrain and vegetation that conceals the layout from view even while riding in the front row, with the compromised tree line from Tatsu’s installation not as bad as I might have imagined. You crest the lift cast in the shadows of California pines, and the first drop down the hillside is veritably an enclosed tunnel of bark and chlorophyll.

Most of all, I love the dramatic structure of the layout itself. Schwarzkopf, heavily directed by Randall Duell, designed a roller coaster in which every moment is predicated by the others, with not one curve or drop random or happenstance. The narrative utilized is of a very conservative aesthetic that can be clearly (and, I think, deliberately) articulated using conventional story telling terms, starting with the rising action, turning point, climax, falling action and resolution. The layout starts with a series of three curving dives that mirror each other (rising action), a sequence that establishes a pattern while slowly raising the stakes on each iteration: the second two drop further than the first, and the last curve has a stronger lateral whip than the previous two. There is then a pause with a mini block brake that sets up a long descending ramp

Most of all, I love the dramatic structure of the layout itself. Schwarzkopf, heavily directed by Randall Duell, designed a roller coaster in which every moment is predicated by the others, with not one curve or drop random or happenstance. The narrative utilized is of a very conservative aesthetic that can be clearly (and, I think, deliberately) articulated using conventional story telling terms, starting with the rising action, turning point, climax, falling action and resolution. The layout starts with a series of three curving dives that mirror each other (rising action), a sequence that establishes a pattern while slowly raising the stakes on each iteration: the second two drop further than the first, and the last curve has a stronger lateral whip than the previous two. There is then a pause with a mini block brake that sets up a long descending ramp (turning point) that provides a crisp sense of acceleration and hence emotional anticipation of the centerpiece vertical loop (climax). It’s such an effective build-up that by the time I’m inverted 180° I’m thinking “this is soooo cool!”, even though I’ve already been turned upside down 34 times on all the other coasters at Magic Mountain and didn’t think half as much of any of Scream’s gargantuan somersaults. The difference is particularly striking when compared to its east coast sibling the Sooperdooperlooper, which although shares a great deal of the same characteristics, comes off as feeling like a goofy, fun lark with the loop placed right at the beginning of the ride and followed by a grab-bag layout content to wander around the landscape, rather than the disciplined

(turning point) that provides a crisp sense of acceleration and hence emotional anticipation of the centerpiece vertical loop (climax). It’s such an effective build-up that by the time I’m inverted 180° I’m thinking “this is soooo cool!”, even though I’ve already been turned upside down 34 times on all the other coasters at Magic Mountain and didn’t think half as much of any of Scream’s gargantuan somersaults. The difference is particularly striking when compared to its east coast sibling the Sooperdooperlooper, which although shares a great deal of the same characteristics, comes off as feeling like a goofy, fun lark with the loop placed right at the beginning of the ride and followed by a grab-bag layout content to wander around the landscape, rather than the disciplined tone-poem of Revolution. This is followed by a couple

tone-poem of Revolution. This is followed by a couple more swooping terrain curves echoing on a smaller scale the first, plus a tunnel (falling action). The train emerges to a long straight away threaded through the loop, allowing ample time to witness what we achieved, and then concluding with a helix finale (resolution). The resolving powers of the helix are literally manifest in the geometry itself, representing the return of a full circle. It’s such a classic and subliminal roller coaster metaphor that the idea of a ‘helix finale’ now risks overexposure and redundancy in most layouts I ride these days that feature it. And now that that has all been said, my paradox…

more swooping terrain curves echoing on a smaller scale the first, plus a tunnel (falling action). The train emerges to a long straight away threaded through the loop, allowing ample time to witness what we achieved, and then concluding with a helix finale (resolution). The resolving powers of the helix are literally manifest in the geometry itself, representing the return of a full circle. It’s such a classic and subliminal roller coaster metaphor that the idea of a ‘helix finale’ now risks overexposure and redundancy in most layouts I ride these days that feature it. And now that that has all been said, my paradox…

I hated, hated, hated, hated my individual experiences on the Revolution. The three rides I took over two days at the park were the three worst I would have out of any at Magic Mountain. The fact that I rode it three times and didn’t walk away after the first is either a testament to my faith in Schwarzkopf that it was a fluke, or to my latent sadomasochism. It all came down to one thing: those retrofitted over-the-shoulder restraints. I’ve never had as much of a problem with OTSRs as I have on the Revolution’s unnecessary add-ons to the original lapbar-only design. It’s quite clear they were added as a secondary restraining device spurred by a nervous management or insurer after they reasoned that it goes upside down and the laws of centrifugal force are unlikely to be observed by the rowdy teenage crowd. But because they’re an ad-hoc extension to a vehicle body never designed for shoulder harnesses, they’re fitted much higher than a normal restraint would be and come down nowhere near any actual shoulders unless an NBA player is visiting the park. Instead the bar come right over my ears and the top part of my head, and whenever the cars enter or exit a turn (we’re still dealing with 1970’s design techniques here, before heartlining concepts were fully developed by Stengel) the rock hard foam would knock right into my temple area, sometimes violently. No matter how much I tried to guard against it with defensive riding positions, there was no avoiding it: I would be taking a cranial beating if I wanted to ride the Revolution. The bottom part of the restraints also feature these weird inward spikes

are unlikely to be observed by the rowdy teenage crowd. But because they’re an ad-hoc extension to a vehicle body never designed for shoulder harnesses, they’re fitted much higher than a normal restraint would be and come down nowhere near any actual shoulders unless an NBA player is visiting the park. Instead the bar come right over my ears and the top part of my head, and whenever the cars enter or exit a turn (we’re still dealing with 1970’s design techniques here, before heartlining concepts were fully developed by Stengel) the rock hard foam would knock right into my temple area, sometimes violently. No matter how much I tried to guard against it with defensive riding positions, there was no avoiding it: I would be taking a cranial beating if I wanted to ride the Revolution. The bottom part of the restraints also feature these weird inward spikes that come down right about at nipple height, which taken altogether made me wonder if the restraints were designed by a dominatrix.

that come down right about at nipple height, which taken altogether made me wonder if the restraints were designed by a dominatrix.

There’s no rational reason for this. The only thing they protect against is the nuclear failure of someone falling out completely should the lapbars fail and the train stalls upside down, an incident that has occurred precisely zero times on any of Schwarzkopf’s some 30 looping installations that combined carry millions of passengers per year and have an operating record of 35 years. There’s another version right in Los Angeles with a lapbar only design, two inversions forward and backward, and an artificial, variable acceleration method to achieve the necessary centrifugal force, if the lawyers need a working demonstration with a long running history and under the same state’s amusement safety legislation. It protects against an imaginary danger. But they actively inflict some lesser form of real injury on nearly every passenger that rides, and because none of these minor injuries could ever be causally linked to any potential litigation, nothing will be done. As long as Six Flags has no motivation to invest in a correction they don’t perceive it as an issue harmful to business, we should be writing them letters letting our feelings be known… or better yet, figure out whoever covers Magic Mountain’s insurance and write them a letter alerting them to the ‘possibility’ of injury. Coaster geeks of the world, unite! Together we are strong… except for in the presence of uncomfortable restraints, and then we’re a cowering coalition of crybabies.

with a long running history and under the same state’s amusement safety legislation. It protects against an imaginary danger. But they actively inflict some lesser form of real injury on nearly every passenger that rides, and because none of these minor injuries could ever be causally linked to any potential litigation, nothing will be done. As long as Six Flags has no motivation to invest in a correction they don’t perceive it as an issue harmful to business, we should be writing them letters letting our feelings be known… or better yet, figure out whoever covers Magic Mountain’s insurance and write them a letter alerting them to the ‘possibility’ of injury. Coaster geeks of the world, unite! Together we are strong… except for in the presence of uncomfortable restraints, and then we’re a cowering coalition of crybabies.

I don’t have anywhere near the same problem with Arrow’s horsecollar restraints. At 5’10” they fit perfectly on me, above the shoulders but below the earlobes, allowing me to enjoy the beautifully awful transitions without any risk of injury or discomfort. Nevertheless I approached Viper slightly apprehensive, though I did admire the presence of the spotless white support structure and vibrant red track looming over the rugged desert landscape. The coaster looks like the year is still 1990, but the empty queue line betrays its true age. Was it really that long ago when the Viper was still a landmark amongst the nation’s thrill rides, especially thanks to its leading role in the old “America’s Greatest Roller Coaster Thrills in 3D” VHS tapes? Did anyone else grow up with those? With the fake speed countdowns on the first drops, poorly dubbed scream track recycled on every video, and Ron Toomer’s infamous interview during which he explained that he designs his roller coasters by fiddling with a wire left on his desk? Viper owned that video. For so many years Viper was one of those unattainable dream coasters cruelly constructed on the opposite side of the country from myself. Now I have nearly the entire station platform to myself and it seems so ordinary, but I keep my unique affinity for the Viper over all other Magic Mountain coasters in the back of my mind as I pull down the orange horsecollar and start the intimidating 188’ tall climb skywards, unsure if the ride would live up to its past reputation or if I had reason to fear for my health over the next minute or so.

With the fake speed countdowns on the first drops, poorly dubbed scream track recycled on every video, and Ron Toomer’s infamous interview during which he explained that he designs his roller coasters by fiddling with a wire left on his desk? Viper owned that video. For so many years Viper was one of those unattainable dream coasters cruelly constructed on the opposite side of the country from myself. Now I have nearly the entire station platform to myself and it seems so ordinary, but I keep my unique affinity for the Viper over all other Magic Mountain coasters in the back of my mind as I pull down the orange horsecollar and start the intimidating 188’ tall climb skywards, unsure if the ride would live up to its past reputation or if I had reason to fear for my health over the next minute or so.

The curving first drop suggests the Arrow mega-coaster has aged fairly well, the wheels all aligned and rolling smoothly, although the physical track still suffers from some hard jolts that indicates Arrow still hadn’t figured out how to calculate variable banking before the end of the 80’s. The first maneuver has the famous profile of the long upward ramp terminating in a vertical loop of roughly the same radius

The curving first drop suggests the Arrow mega-coaster has aged fairly well, the wheels all aligned and rolling smoothly, although the physical track still suffers from some hard jolts that indicates Arrow still hadn’t figured out how to calculate variable banking before the end of the 80’s. The first maneuver has the famous profile of the long upward ramp terminating in a vertical loop of roughly the same radius as every other vertical loop Arrow ever built (principles of geometric scaling also being a crippling weakness of Toomer’s). It’s a profile I sort of like as the inversion is much more disorienting force-wise than it would have been if long and drawn out as they finally figured out on the Tennessee Tornado. That’s good for me as there’s two more of these loops just around the lightning elevated turnaround. All good fun, although the third loop has a rather bad bump at the top as if Ron pinched a point too hard when forming his coat hangers.

as every other vertical loop Arrow ever built (principles of geometric scaling also being a crippling weakness of Toomer’s). It’s a profile I sort of like as the inversion is much more disorienting force-wise than it would have been if long and drawn out as they finally figured out on the Tennessee Tornado. That’s good for me as there’s two more of these loops just around the lightning elevated turnaround. All good fun, although the third loop has a rather bad bump at the top as if Ron pinched a point too hard when forming his coat hangers.

Aside from the hair product advertisements that jolt is the most offensive moment on the entire ride. The momentum is halted for a midcourse brake run, and then it slowly picks up speed again on a shallow serpentine descent that sets up the double-inversion batwing element quite nicely. This element can be a little bit jarring but it’s also my favorite of the ride if only for the increasing rarity. There’s then a cactus-clipping ground level curve that feeds into the barrel of the double corkscrew, copied and pasted directly from the blueprints of Knott’s miniscule corkscrew originator. That’s the principle setback with the Arrow mega-looping coaster designs. Since they don’t adjust the scale of the inversions from the standard issue, the ride feels progressively smaller until a 70 mph monster is imitating verbatim a 70 foot tall compact production model. Although smaller and older, King’s Island’s Vortex manages this better with the aerial corkscrews threading the loops and then rapidly descending into a partly subterranean batwing as a grand climax. There’s no such rush to the finish line on Viper; after the corkscrews there’s an extemporaneous stretch

directly from the blueprints of Knott’s miniscule corkscrew originator. That’s the principle setback with the Arrow mega-looping coaster designs. Since they don’t adjust the scale of the inversions from the standard issue, the ride feels progressively smaller until a 70 mph monster is imitating verbatim a 70 foot tall compact production model. Although smaller and older, King’s Island’s Vortex manages this better with the aerial corkscrews threading the loops and then rapidly descending into a partly subterranean batwing as a grand climax. There’s no such rush to the finish line on Viper; after the corkscrews there’s an extemporaneous stretch of track over some uneven desert terrain (which I actually liked just for being a different pace) back to the station. As much as I like

of track over some uneven desert terrain (which I actually liked just for being a different pace) back to the station. As much as I like to champion classic Arrow Dynamic roller coasters, I’d be lying if I said this ride were an underrated gem that lived up to my childhood day dreams. But it’s still an indomitable thrill machine, and when I found an empty set of air gates upon my return I stayed seated, even enjoying it enough to repeat thrice more. And of all the coasters in the park with seven inversions, Viper is the best.

to champion classic Arrow Dynamic roller coasters, I’d be lying if I said this ride were an underrated gem that lived up to my childhood day dreams. But it’s still an indomitable thrill machine, and when I found an empty set of air gates upon my return I stayed seated, even enjoying it enough to repeat thrice more. And of all the coasters in the park with seven inversions, Viper is the best.

I will, however, be championing the modern Arrow Dynamic roller coaster that’s situated directly to the left: the dark, sinister complement to Viper’s bright white dexterity, X2. The 2008 re-launch of the original 4D prototype saw new and improved trains, paint, soundtrack, flamethrowers and an overarching philosophy to tie it all together. I interpreted it to be this: More than just a roller coaster, X2 is a kinetic metaphor of our simultaneous terror of and attraction to the unstoppable behemoth that is popular culture. As a hypermasculine Beelzebub incarnate that inhales sulfur and exhales rock ‘n’ roll, it dwarfs anyone who dares not to surrender to its awesome but horrible power. God is not dead, the ancient deities are still alive today in the faces of mass media, controlling human destiny with the electric bolts pulsing through the information superhighway, and Los Angeles is the modern Pop Pantheon from which the Gods reign supreme. But is it these Pop Gods that have created us, or did we create these Gods? We recognize that this culture is entirely mortal-produced; in fact I am responsible for its creation, participants all of us in the market economy and all of its destructive tendencies. But what is destruction but another form of creation?

I will, however, be championing the modern Arrow Dynamic roller coaster that’s situated directly to the left: the dark, sinister complement to Viper’s bright white dexterity, X2. The 2008 re-launch of the original 4D prototype saw new and improved trains, paint, soundtrack, flamethrowers and an overarching philosophy to tie it all together. I interpreted it to be this: More than just a roller coaster, X2 is a kinetic metaphor of our simultaneous terror of and attraction to the unstoppable behemoth that is popular culture. As a hypermasculine Beelzebub incarnate that inhales sulfur and exhales rock ‘n’ roll, it dwarfs anyone who dares not to surrender to its awesome but horrible power. God is not dead, the ancient deities are still alive today in the faces of mass media, controlling human destiny with the electric bolts pulsing through the information superhighway, and Los Angeles is the modern Pop Pantheon from which the Gods reign supreme. But is it these Pop Gods that have created us, or did we create these Gods? We recognize that this culture is entirely mortal-produced; in fact I am responsible for its creation, participants all of us in the market economy and all of its destructive tendencies. But what is destruction but another form of creation?

At the heart of this terror, when confronting X2 one is made to feel insignificant. It’s impossible to comprehend that which encompasses our entire constitutive being. The towering blood red and charcoal gray Olympus is unfathomably massive, in scale, technology and expense; all flowing with a pop-synergy that’s built from exabytes of cultural discourse which no one player controls. And yet as the banner hanging in this “Coliseum of Thrill” reminds: “here you stand”. This reality is all your experience. No one else, not even God, can take that away from you. You were born alone, you will die alone, and you will ride X2 alone. Although the ride operators will do their best to pair single riders.

The station is an impressive sight to behold: the giant air-hangar-like structure built to encompass the massive, 20-foot wide trains. Overhead is an enormous LED screen replaying the animated promotional video of the coaster which depicts the ride in an even darker and epic nature than it already is, while meanwhile the speakers play a creepily ambient mix of an echoing female voice whispering “X2”, a male voice repeating (each time a tone lower) “Is everybody in? Is everybody in? The ceremony is about to begin…” The one place where Six Flags messed up was in the lighting. For some reason all the lights in the station are a flat white, when I would have expected at least red or ultraviolet filters, if not an expensive show-lighting package. Such a simple change would have made such a dramatic improvement in the

The station is an impressive sight to behold: the giant air-hangar-like structure built to encompass the massive, 20-foot wide trains. Overhead is an enormous LED screen replaying the animated promotional video of the coaster which depicts the ride in an even darker and epic nature than it already is, while meanwhile the speakers play a creepily ambient mix of an echoing female voice whispering “X2”, a male voice repeating (each time a tone lower) “Is everybody in? Is everybody in? The ceremony is about to begin…” The one place where Six Flags messed up was in the lighting. For some reason all the lights in the station are a flat white, when I would have expected at least red or ultraviolet filters, if not an expensive show-lighting package. Such a simple change would have made such a dramatic improvement in the ominous ambiance. The fact that the pre-ride atmosphere is still fairly tense is a testament to how effective the presentation has been so far; basically it just has to look really freakin’ expensive for the subliminal aesthetic to take hold, something Magic Mountain did quite well. The new trains, in a bid to keep weight to a minimum for a smoother ride, have far less ornamentation than the old ones (with the big purple fiberglass “X” casings) but to greater visual effect. Not hiding the technology behind the ride is another psychological mindgame X2 plays before we’re ready to depart, the complicated inner workings teasing us to put it in a perspective we can understand. The restraints are an unusual but effective design, with two halves of “butterfly wings” folding around the sides and sliding downward on a vertical accordion spring

ominous ambiance. The fact that the pre-ride atmosphere is still fairly tense is a testament to how effective the presentation has been so far; basically it just has to look really freakin’ expensive for the subliminal aesthetic to take hold, something Magic Mountain did quite well. The new trains, in a bid to keep weight to a minimum for a smoother ride, have far less ornamentation than the old ones (with the big purple fiberglass “X” casings) but to greater visual effect. Not hiding the technology behind the ride is another psychological mindgame X2 plays before we’re ready to depart, the complicated inner workings teasing us to put it in a perspective we can understand. The restraints are an unusual but effective design, with two halves of “butterfly wings” folding around the sides and sliding downward on a vertical accordion spring to rest at the perfect height, ensuring a secure fit that’s minimally intrusive to the ragdoll flailing of hands, legs and neck that we’ll be doing. On my first ride I found myself fumbling for a seatbelt or something to go over my lap. There wasn’t any. While your chest is secure, the lower part of your body remains surprisingly vulnerable, a sensation more discomforting than freeing as we’re released from the station and sent around the first curve in reverse.

to rest at the perfect height, ensuring a secure fit that’s minimally intrusive to the ragdoll flailing of hands, legs and neck that we’ll be doing. On my first ride I found myself fumbling for a seatbelt or something to go over my lap. There wasn’t any. While your chest is secure, the lower part of your body remains surprisingly vulnerable, a sensation more discomforting than freeing as we’re released from the station and sent around the first curve in reverse.

The mark of a truly great ride is that it provides a complete experience before the meaty visceral action has even begun. X2 is the grand champion of this strategy, marrying an excellent, multi-stage introduction that teases out even the slightest of psychological anxieties to a main sequence that genuinely does bite as loud as it barks. On my first ride I was a bit nervous anyway as I had no idea what a 4D coaster experience would feel like, while knowing that X2 had a love-it-or-hate-it reputation but not yet knowing which camp I would fall into. Once on the first curve when it’s time to do-or-die, the on-board soundtrack rings in a tinny recording of “It Had To Be You”, of all things. The seats seem to nervously swivel onto their backs, demonstrating the forth-rail technology for us a bit, and then it’s into the lift hill. Sinatra’s voice gives way to an electronic crackle, a voice rhetorically questions “are you ready?”,

The mark of a truly great ride is that it provides a complete experience before the meaty visceral action has even begun. X2 is the grand champion of this strategy, marrying an excellent, multi-stage introduction that teases out even the slightest of psychological anxieties to a main sequence that genuinely does bite as loud as it barks. On my first ride I was a bit nervous anyway as I had no idea what a 4D coaster experience would feel like, while knowing that X2 had a love-it-or-hate-it reputation but not yet knowing which camp I would fall into. Once on the first curve when it’s time to do-or-die, the on-board soundtrack rings in a tinny recording of “It Had To Be You”, of all things. The seats seem to nervously swivel onto their backs, demonstrating the forth-rail technology for us a bit, and then it’s into the lift hill. Sinatra’s voice gives way to an electronic crackle, a voice rhetorically questions “are you ready?”, and then the real rock-and-roll begins.

and then the real rock-and-roll begins.

The brilliance of this beginning is partly inherent in the ride’s design: we’re traveling backwards so there’s no way to see how much farther there is to go before we’re at the precipice of a sheer vertical dive. Instead we get to watch the earth move farther away below us, the coaster is situated on top of a hill so we can see the entire postmodern steel landscape of Magic Mountain laid out in front of us, the parallax slowly shrinking it into miniature as we inch further up and away (everyone gets a clear view no matter the seat). The serene, God-like perspective is contrasted with the rock music overlaid with a hyperactive collage of movie quotes, notably from R. Lee Ermey’s intense drill sergeant from Full Metal Jacket (Featured: “I’ve got your name! You will not laugh, you will not cry!” Not Featured: “Do you suck dicks? I bet you could suck a golf ball through a garden hose!”). It is here where that philosophy espoused in the review’s opening paragraphs is most immediate; the panoptic scale of the physical and pop-cultural environment simultaneously highlights while rendering infinitesimal the weight of individual experience.

It comes to a head when we crest the 215’ lift hill, the world (both visual and audible) abruptly disappears from view, and all that remains is the sound of a heartbeat. We know we’re sitting on a razor’s edge, and our 5-ton train has just now been released to the influence of gravity alone, but the enormous bubble of tension can’t be popped just yet. There’s a small fake-out drop and rise before getting to the main drop, during which our seats rotate us forward so we’re now in a backwards flying position staring straight down at the ground over 200 feet below. Holy crap. I’m staring down a vertical red column that I realize is our track, and suddenly Aerosmith cuts in with “goooooing down” and our train plummets 90°. The seats flip us a further 90° so we’re falling head first upside down. We flip onto our backs just before hitting the bottom, a smooth 76 mph pullout that demonstrates an unbelievable amount of force and power. Just as smoothly we surge straight upward and over into the first raven turn, a vertical half-loop of sorts that the rotating seats keep us upright over the entire arc. This produces some spectacular airtime over the crest (remember, there’s nothing over your lap so you are out of your seat), and as the entire twisted metal salad of track comes into view with nothing above or below me, I can only yell out one thing: “FUCK YEAH!!!”

first upside down. We flip onto our backs just before hitting the bottom, a smooth 76 mph pullout that demonstrates an unbelievable amount of force and power. Just as smoothly we surge straight upward and over into the first raven turn, a vertical half-loop of sorts that the rotating seats keep us upright over the entire arc. This produces some spectacular airtime over the crest (remember, there’s nothing over your lap so you are out of your seat), and as the entire twisted metal salad of track comes into view with nothing above or below me, I can only yell out one thing: “FUCK YEAH!!!”

From the station to the first raven turn is probably about the most mind-blowing start to a roller coaster I’ve ever come across. After this it lets off the gas a bit (the music is all but inaudible by this point, not that anyone could remember to listen for it), although the next element is still keeping in the spirit. There’s a small, low camelback hill similar in profile to nearby Goliath’s, only the trains take advantage of the near-weightlessness to do a breezy backward somersault courtesy of the secondary set of rails. This is probably the best moment to savor the 4D selling point; at other times when it’s in use it can be hard to tell exactly what’s going on. The next maneuver, a “luge turn” (sort of a shallow fan curve with the rotating seats tipped on their backs so riders glide through it luge-style) slows the pace down for a moment’s breather, although it’s also the point where Arrow most messed up their analysis by trying to build a heartlined transition into the banking with trains that can’t heartline due to the 20-foot span, so there’s a bit

by this point, not that anyone could remember to listen for it), although the next element is still keeping in the spirit. There’s a small, low camelback hill similar in profile to nearby Goliath’s, only the trains take advantage of the near-weightlessness to do a breezy backward somersault courtesy of the secondary set of rails. This is probably the best moment to savor the 4D selling point; at other times when it’s in use it can be hard to tell exactly what’s going on. The next maneuver, a “luge turn” (sort of a shallow fan curve with the rotating seats tipped on their backs so riders glide through it luge-style) slows the pace down for a moment’s breather, although it’s also the point where Arrow most messed up their analysis by trying to build a heartlined transition into the banking with trains that can’t heartline due to the 20-foot span, so there’s a bit of a lurch on the entry and exit of this turn. There’s also an odd moment where I realize, “weren’t we going backward at the beginning of the ride?” That’s explained by the inverted track with the seats technically rotated upside down as well. It pays off with the half barrel roll that follows. This is not as extreme a maneuver as it could be imagined to be. Since we’re kept upright through the whole thing, it feels more like a simple 90° banked turn than anything else, albeit one in the geometric space of an M.C. Escher drawing. At the bottom are a set of flame throwers which were the only special

of a lurch on the entry and exit of this turn. There’s also an odd moment where I realize, “weren’t we going backward at the beginning of the ride?” That’s explained by the inverted track with the seats technically rotated upside down as well. It pays off with the half barrel roll that follows. This is not as extreme a maneuver as it could be imagined to be. Since we’re kept upright through the whole thing, it feels more like a simple 90° banked turn than anything else, albeit one in the geometric space of an M.C. Escher drawing. At the bottom are a set of flame throwers which were the only special effect from the original make-over announcement to actually get installed (fog and tunnels were also promised but never materialized), and generally only improve the ride experience at night. During the day you’re looking up at the sun anyway so they’re easy to miss especially if they’re not timed right. There’s one more raven turn, not as epic as the big brother next to it but features some strong G-forces due to the tight circumference, and then a second half barrel roll, also smaller (but not more forceful) than the first. The train slides into the brakes and the ride is over, Rage Against The Machine pounding over the speakers to congratulate our accomplishment. In some respects it is a silly and overly macho tone for a ride, perpetuating the unfortunately one-sided gender preference of the roller coaster hobby, but it still hit a nerve in me and I was grinning ear to ear when we got back.

effect from the original make-over announcement to actually get installed (fog and tunnels were also promised but never materialized), and generally only improve the ride experience at night. During the day you’re looking up at the sun anyway so they’re easy to miss especially if they’re not timed right. There’s one more raven turn, not as epic as the big brother next to it but features some strong G-forces due to the tight circumference, and then a second half barrel roll, also smaller (but not more forceful) than the first. The train slides into the brakes and the ride is over, Rage Against The Machine pounding over the speakers to congratulate our accomplishment. In some respects it is a silly and overly macho tone for a ride, perpetuating the unfortunately one-sided gender preference of the roller coaster hobby, but it still hit a nerve in me and I was grinning ear to ear when we got back.

Yet if I sound a bit less enthused about the rest of the ride after the first raven turn, that’s because I am less enthused. The first drop is where all the really imaginative uses of the 4D technology are put to use, and as the scale diminishes so does the ambition to really experiment with the technology. As crazy as the independent axis seats sound on paper, the truth is that for the majority of the layout they’re used to neutralize and control the experience, not to add anything more to it. There are only two times when riders are upside down, both happen within the first half of the ride action. I feel like the second raven turn and/or one of the half rolls are crying out for a 540° seat rotation rather than a simple 180°. This isn’t even much of a criticism in itself –  there’s only so much you can take in a single ride before some riders will reach their threshold and need it to slow down for the remainder in order to enjoy it – but the second half of the layout was also marred by some rather unpleasant vibrations in the winged seating arrangement (particularly through the half-roll and into the second raven turn), strangely not present on the high-speed sections early in the ride. That brings up one of the primary points of contention regarding X2: Is it rough?

there’s only so much you can take in a single ride before some riders will reach their threshold and need it to slow down for the remainder in order to enjoy it – but the second half of the layout was also marred by some rather unpleasant vibrations in the winged seating arrangement (particularly through the half-roll and into the second raven turn), strangely not present on the high-speed sections early in the ride. That brings up one of the primary points of contention regarding X2: Is it rough?

In a word, yes. However, even before I ever rode it myself I was surprised by how many enthusiasts wrote that they found it extremely rough but still loved it anyway and put it near the top of their lists of best roller coasters. Normally that sort of reception is unheard of amidst enthusiast circles – if it’s rough, the ride is flat out of luck – so I knew I had to be dealing with something pretty awesome (and as my review indicates, I agree). I’m even uncomfortable using the term ‘rough’ to describe X2 since I think that leaves out a bit of color as to exactly what sort of experience you get. It’s certainly not rough in the loose wheel grip notion that many older Arrow coasters encounter, nor is it from a coat hanger trackwork quality (except for the transitions in the luge-turn

of reception is unheard of amidst enthusiast circles – if it’s rough, the ride is flat out of luck – so I knew I had to be dealing with something pretty awesome (and as my review indicates, I agree). I’m even uncomfortable using the term ‘rough’ to describe X2 since I think that leaves out a bit of color as to exactly what sort of experience you get. It’s certainly not rough in the loose wheel grip notion that many older Arrow coasters encounter, nor is it from a coat hanger trackwork quality (except for the transitions in the luge-turn as already noted, something S&S Arrow would figure out a solution for on their next coaster, Eejanaika). It’s at its worst during the vertical oscillation

as already noted, something S&S Arrow would figure out a solution for on their next coaster, Eejanaika). It’s at its worst during the vertical oscillation of the winged seating when it can kinda hurt the base of your neck, and when it’s running well that roughness really just implies a much higher than average level of intensity and aggressiveness, which I wouldn’t categorize as roughness but rather a deliberate design feature. There do seem to be some issues with the double rail, rack-and-pinion gear system that allows the seats

of the winged seating when it can kinda hurt the base of your neck, and when it’s running well that roughness really just implies a much higher than average level of intensity and aggressiveness, which I wouldn’t categorize as roughness but rather a deliberate design feature. There do seem to be some issues with the double rail, rack-and-pinion gear system that allows the seats to rotate, like the tolerances are too loose allowing for some unpredicted drift in the seat rotation. This was mostly observed in the low-speed zones, particularly the turn out of the station when the seats shuttered back and forth a bit, though once it picked up speed this ceased to be as much of a problem (contrary to expectations, as I would think high speeds would magnify such issues rather than tone them down) . Perhaps this also relates to why the section of track along the far back run was rougher than the rest. However, the last ride I would take between my two days at Magic Mountain at night was in the back row of X2, and our vehicles whistled through the course like it was the easiest thing in the world, a final encounter in which everything played out so perfectly that my appetite was well-whetted for a return to Valencia’s iron playground before I had even stepped off the exit platform for the very last time. It was a wild, crazy, insane experience… like Jekyll and Hyde.

to rotate, like the tolerances are too loose allowing for some unpredicted drift in the seat rotation. This was mostly observed in the low-speed zones, particularly the turn out of the station when the seats shuttered back and forth a bit, though once it picked up speed this ceased to be as much of a problem (contrary to expectations, as I would think high speeds would magnify such issues rather than tone them down) . Perhaps this also relates to why the section of track along the far back run was rougher than the rest. However, the last ride I would take between my two days at Magic Mountain at night was in the back row of X2, and our vehicles whistled through the course like it was the easiest thing in the world, a final encounter in which everything played out so perfectly that my appetite was well-whetted for a return to Valencia’s iron playground before I had even stepped off the exit platform for the very last time. It was a wild, crazy, insane experience… like Jekyll and Hyde.

Next: Knott’s Berry Farm and Adventure City.

Comments