Alton, Staffordshire, England, UK – Thursday, June 24th, 2010

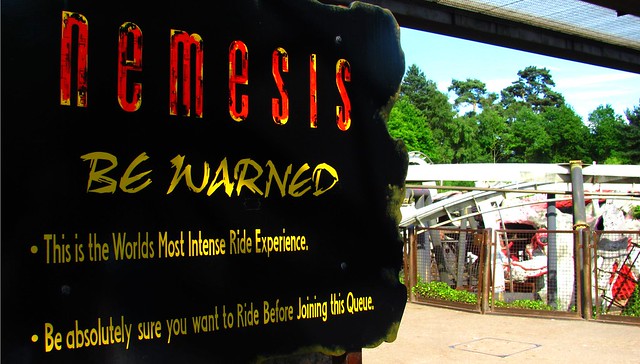

Nemesis is a bloody brilliant roller coaster.

This review could end here. For those that have already been on it I have nothing further to add that they won’t already know; and for those who haven’t, then the single-sentence review above will be as much persuasion as I can manage to get them to join the first group as soon as possible. I don’t believe a more universally praised roller coaster has ever been built. Every other ‘Great Roller Coaster’ has its faction of doubters somewhere, but not so much for Nemesis. It has the smoothness and grace to please the established B&M devotees but with a forcefulness and freneticism that will convert even the most hardened “B&M R Boring” naysayers. It has the setting and storyline that Disney diehards go gaga over, yet never neglects the raw, unfettered thrills the adrenaline junkies are craving. And for those world travelers that have already seen everything under the sun, Nemesis will still offer a unique sequence of elements in a never before-or-again attempted location that can’t be found anywhere else. That’s not to say it’s in everyone’s top ten, in fact it’s relatively few people’s singular all-time favorite attraction, and some may claim that it was overhyped by an aggressively loyal fanbase, others might find it over too quickly or have ridden it on a slow or rough day. But for those forty-five seconds or so from the crest of the lift to the brake run, no matter what your judgment criteria are (unless you’re a wimp), you will at least enjoy your ride on Nemesis. By how much, I can’t say. For me, it’s in my top five.

yet never neglects the raw, unfettered thrills the adrenaline junkies are craving. And for those world travelers that have already seen everything under the sun, Nemesis will still offer a unique sequence of elements in a never before-or-again attempted location that can’t be found anywhere else. That’s not to say it’s in everyone’s top ten, in fact it’s relatively few people’s singular all-time favorite attraction, and some may claim that it was overhyped by an aggressively loyal fanbase, others might find it over too quickly or have ridden it on a slow or rough day. But for those forty-five seconds or so from the crest of the lift to the brake run, no matter what your judgment criteria are (unless you’re a wimp), you will at least enjoy your ride on Nemesis. By how much, I can’t say. For me, it’s in my top five.

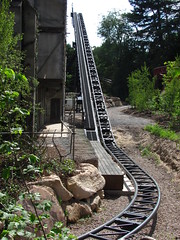

The story behind how Nemesis came to be is well-told amid enthusiast circles. Originally it was to be an Arrow Dynamics pipeline coaster (the proposed projects known as Secret Weapons 1 & 2), but technical delays with the concept at Arrow delayed things long enough for coaster auteur John Wardley to get a taste of the brand-new Batman at Six Flags Great America, after which he said to Arrow, “Sod this, we’re buying from Walter and Claude.” Of course there are height limitations against the park so rather than build upwards they had to build downwards into the ground. Given that Alton Towers as a theme park was still in its relative infancy with only a few compact production model rides, the imagination staggers in conceiving how the newly in-charge Tussauds Group managed to approve a budget requiring this much canyon sculpting and tunnel blasting when the successfully well-established Alton of today is barely able to get approval to build more than one shed for their major new attractions. The extensive terrain interaction is undoubtedly at the core of Nemesis’ success, and the park and its fans are proud to claim that it’s because of these strict limitations that forced creative solutions to result in an attraction that’s far better than it would have otherwise been at an unrestricted American-style park; something that I think was also true for maybe one or two other attractions in the decade and a half since (the rest all have an air of ‘compromisation’ rather than ‘creative solution’), but even then Nemesis alone would be enough to compensate for nearly any of the Tower’s other shortcomings.

in-charge Tussauds Group managed to approve a budget requiring this much canyon sculpting and tunnel blasting when the successfully well-established Alton of today is barely able to get approval to build more than one shed for their major new attractions. The extensive terrain interaction is undoubtedly at the core of Nemesis’ success, and the park and its fans are proud to claim that it’s because of these strict limitations that forced creative solutions to result in an attraction that’s far better than it would have otherwise been at an unrestricted American-style park; something that I think was also true for maybe one or two other attractions in the decade and a half since (the rest all have an air of ‘compromisation’ rather than ‘creative solution’), but even then Nemesis alone would be enough to compensate for nearly any of the Tower’s other shortcomings.

The storyline behind Nemesis’ plot is not as well told, seeming to only remain as part of fansite literature and no longer part of the actual guest experience. I was disappointed to learn the ‘official’ plot tries to be too literal, claiming that the alien creature (never mind that it’s really just a giant fiddler crab) was buried underground for millennia only to be discovered when excavation work was done, and after a battle with the military they wrangled the creature down with the steel represented by the ride’s track. This seems incongruous to the actual design of the monster station which suggests the track is actually the creature’s tendrilous legs. That was my favorite detail as it indicates self awareness that the monster theme is only an abstract metaphor for the roller coaster experience, and allows one to appreciate the stand-alone aesthetic qualities without having to indulge in some silly, self-serious story for it all to have any meaning. I’m all for themeing but only when it makes the rider’s experience more real, not less. Rusted metal, craggy shoals and the red rivers (which we don’t need to suppose is actual blood, just that there’s a unique aesthetic significance to the color) are evocative just as emotional queues, in the same way as a visit to an art gallery to view impressionistic paintings. I don’t need the gallery curator standing over my shoulder whispering the backstory that explains why this ‘window into hell’ is located in a museum. Nemesis is an interactive sculpture depicting our simultaneous terror and fascination with alien evils; there’s all my fan-fiction needs to explain Nemesis’ wonderfully conceived visual appearance.

as it indicates self awareness that the monster theme is only an abstract metaphor for the roller coaster experience, and allows one to appreciate the stand-alone aesthetic qualities without having to indulge in some silly, self-serious story for it all to have any meaning. I’m all for themeing but only when it makes the rider’s experience more real, not less. Rusted metal, craggy shoals and the red rivers (which we don’t need to suppose is actual blood, just that there’s a unique aesthetic significance to the color) are evocative just as emotional queues, in the same way as a visit to an art gallery to view impressionistic paintings. I don’t need the gallery curator standing over my shoulder whispering the backstory that explains why this ‘window into hell’ is located in a museum. Nemesis is an interactive sculpture depicting our simultaneous terror and fascination with alien evils; there’s all my fan-fiction needs to explain Nemesis’ wonderfully conceived visual appearance.

That’s enough about the visual, let’s discuss what Nemesis is really all about: the sensual. It’s a very basic, simple roller coaster to analyze, which is why I could have ended this review after the first sentence. In its most simplified form, Nemesis is about being as amazing and intense as it can be at every moment of the layout. “Non-stop action from start to finish, breathlessly paced, never a dull moment, etc.” Anyone that ranks this ride as a favorite can tell you that. No wonder its appeal is broad and instantly recognized by many different enthusiasts. However, that probably simplifies things too much and is missing some nuance that its biggest fans would cry foul if I forgot to mention. Here’s a broader analysis:

That’s enough about the visual, let’s discuss what Nemesis is really all about: the sensual. It’s a very basic, simple roller coaster to analyze, which is why I could have ended this review after the first sentence. In its most simplified form, Nemesis is about being as amazing and intense as it can be at every moment of the layout. “Non-stop action from start to finish, breathlessly paced, never a dull moment, etc.” Anyone that ranks this ride as a favorite can tell you that. No wonder its appeal is broad and instantly recognized by many different enthusiasts. However, that probably simplifies things too much and is missing some nuance that its biggest fans would cry foul if I forgot to mention. Here’s a broader analysis:

Nemesis consists of nine separate ‘beats’ wherein the first four progressively ratchet up the level of visceral excitement, and the remaining five sustain near that maximum level for the rest of the ride duration. (Although numbers seven and nine are exceptions which will be further explicated upon later).

wherein the first four progressively ratchet up the level of visceral excitement, and the remaining five sustain near that maximum level for the rest of the ride duration. (Although numbers seven and nine are exceptions which will be further explicated upon later). Even non-stop intensity can grow monotonous so this distinction about the crescendo nature of the first half is important to note for dramaturgic reasons. The benefits are two-fold, as afforded the ability to delay the fastest point in the layout for several elements by the sharply uneven terrain, it also allows the track to remain perilously close to the rocky landscape which is a vital element to the perceived danger of each moment. The fact that elements take place over a waterfall or through a canyon is fundamental to how the mind understands these maneuvers, i.e. how the setting affects their perception of speed, orientation in space, or if it just makes the rider think “wow, cool!” Although it may be tempting to focus on the pattern of forces applied to the body as if it were designed in a vacuum, Nemesis is working proof that to adequately describe a ride every sight, sound or even smell the rider is expected to experience must be accounted for;

Even non-stop intensity can grow monotonous so this distinction about the crescendo nature of the first half is important to note for dramaturgic reasons. The benefits are two-fold, as afforded the ability to delay the fastest point in the layout for several elements by the sharply uneven terrain, it also allows the track to remain perilously close to the rocky landscape which is a vital element to the perceived danger of each moment. The fact that elements take place over a waterfall or through a canyon is fundamental to how the mind understands these maneuvers, i.e. how the setting affects their perception of speed, orientation in space, or if it just makes the rider think “wow, cool!” Although it may be tempting to focus on the pattern of forces applied to the body as if it were designed in a vacuum, Nemesis is working proof that to adequately describe a ride every sight, sound or even smell the rider is expected to experience must be accounted for; these are just as much sensations as anything the inner ear registers, and as such the roller coaster must be evaluated holistically. The sensorial assault

these are just as much sensations as anything the inner ear registers, and as such the roller coaster must be evaluated holistically. The sensorial assault occurs on all fronts, physical, temporal, perceptual, even tactile. If you catch it on a really slick day, it can all contribute to overstimulation, our synapses racing through so much information that when we get back our hands can’t be kept from trembling. The last reason in favor of Nemesis was simply the non-standard sequence of elements. After riding more Beemers than I’d care to count, it was refreshing to get a totally unique flight path (something Black Mamba can’t lay claim to). It was like rediscovering for the first time the surprise of the company’s formula which had otherwise gone stale.

occurs on all fronts, physical, temporal, perceptual, even tactile. If you catch it on a really slick day, it can all contribute to overstimulation, our synapses racing through so much information that when we get back our hands can’t be kept from trembling. The last reason in favor of Nemesis was simply the non-standard sequence of elements. After riding more Beemers than I’d care to count, it was refreshing to get a totally unique flight path (something Black Mamba can’t lay claim to). It was like rediscovering for the first time the surprise of the company’s formula which had otherwise gone stale.

Now, to outline those nine beats that pack so much punch:

One: The first drop, which is really two separate elements fused together, starting with a 180° left curve, leveling out momentarily to gently dip the rest of the way down the hillside, it’s a deceptively toothless opener never exceeding 20° in angle of descent that nevertheless ranks as one of B&M’s most inspired. Starting at nearly ground-level prevents us from adequately sizing-up the experience that awaits us so we’re left relatively unprepared for when the venom does strike, and the second half squeezed between trees over and through a small rock canyon with bloody waterfall is genius, plain and simple. Gentle and playful, the rider is made curious, drawn into the ride’s narrative, rather than blasted back unprepared like every other big first drop out there.

One: The first drop, which is really two separate elements fused together, starting with a 180° left curve, leveling out momentarily to gently dip the rest of the way down the hillside, it’s a deceptively toothless opener never exceeding 20° in angle of descent that nevertheless ranks as one of B&M’s most inspired. Starting at nearly ground-level prevents us from adequately sizing-up the experience that awaits us so we’re left relatively unprepared for when the venom does strike, and the second half squeezed between trees over and through a small rock canyon with bloody waterfall is genius, plain and simple. Gentle and playful, the rider is made curious, drawn into the ride’s narrative, rather than blasted back unprepared like every other big first drop out there.

Two: A corkscrew, which seems to appear from nowhere (hidden from sight by the vegetated hillside and overhead track until we start flipping into the inversion) and all the more unexpected by the apparent insufficient momentum from the shallow first drop to make inversions feasible just yet. The thrill factor is now present, but most of us are having fun as we’re acclimated to inversions such as this (mostly out in the open) from other similar rides.

Two: A corkscrew, which seems to appear from nowhere (hidden from sight by the vegetated hillside and overhead track until we start flipping into the inversion) and all the more unexpected by the apparent insufficient momentum from the shallow first drop to make inversions feasible just yet. The thrill factor is now present, but most of us are having fun as we’re acclimated to inversions such as this (mostly out in the open) from other similar rides.

Three: A 370° downward helix, this brings the right side of the train very close to ground level while a spectator fence acts as a foot chopper around the first half of its carousel. The ‘attack’ of this maneuver quickly intensifies as the last part dives down a trench, all of it pulling significant positive g-forces that momentarily rivals the helices on Goliath or Raptor. I was told the track around this corner has actually been replaced on multiple occasions due to the heavy stress it takes from the force of the trains.

momentarily rivals the helices on Goliath or Raptor. I was told the track around this corner has actually been replaced on multiple occasions due to the heavy stress it takes from the force of the trains.

Four: The heartline roll reaches the zenith of intensity that Nemesis will serve during its layout. The timing between beats has shortened to the point that changes in dynamics can occur within milliseconds. Unlike similar elements this one has an extremely short and shallow upward ramp so that the instant the train has finished rotating out of the previous helix before it begins to torque riders around again through the inversion. If there even is the slightest pause between moments our attention is only distracted by the startlingly close proximity of the monster station structure beneath our feet. Sitting on the left side of the car watching my shoes hurtling directly towards the creature corpus only to have the lightning rotation of the barrel roll save them by seemingly inches is close of a footchopper as I’ve ever gotten from a B&M product. The right side also comes very close to the protruding eyeball. It’s all such a breathtaking setup that the rollover that follows at the top, one of the fastest and most aggressive I’ve ever experienced, seems like a foregone conclusion.

beneath our feet. Sitting on the left side of the car watching my shoes hurtling directly towards the creature corpus only to have the lightning rotation of the barrel roll save them by seemingly inches is close of a footchopper as I’ve ever gotten from a B&M product. The right side also comes very close to the protruding eyeball. It’s all such a breathtaking setup that the rollover that follows at the top, one of the fastest and most aggressive I’ve ever experienced, seems like a foregone conclusion.

Five: The first so-called “stall turn”, this curve has an oblong shape with a long uphill banked lead-in, a tight radius at the top that quickly whips passengers around 180°, and then another long straight descent back down the canyon. Although the previous heartline roll was arguably the coaster’s climax, this one sustains the excitement mostly by its ingenious use of terrain. A pink waterfall traces very close to the vehicles pathway for the entire length of the banking lead-in, and riders on the right side of the train can feel the spray of the water kicking up from the rocks against their legs (provided they’re not wearing long pants, of course). Like Blue Tornado’s hedge-trimming helix, this tactic is particularly effective because it mentally destroys the invisible barrier safeguarding the rider’s enclosed subjective experience from the objective world they see whizzing around them. To reach out and feel that ‘external world’ (in this case, outside the ride carriage) is to reaffirm that, yes, we’re not in a videogame, these canyon wall and waterfall are very real

Although the previous heartline roll was arguably the coaster’s climax, this one sustains the excitement mostly by its ingenious use of terrain. A pink waterfall traces very close to the vehicles pathway for the entire length of the banking lead-in, and riders on the right side of the train can feel the spray of the water kicking up from the rocks against their legs (provided they’re not wearing long pants, of course). Like Blue Tornado’s hedge-trimming helix, this tactic is particularly effective because it mentally destroys the invisible barrier safeguarding the rider’s enclosed subjective experience from the objective world they see whizzing around them. To reach out and feel that ‘external world’ (in this case, outside the ride carriage) is to reaffirm that, yes, we’re not in a videogame, these canyon wall and waterfall are very real and potentially very lethal if they get any closer. The return leg of the turn drops near the rocks beneath the opposing track where it reaches the lowest point of the

and potentially very lethal if they get any closer. The return leg of the turn drops near the rocks beneath the opposing track where it reaches the lowest point of the layout some 120 feet below the lift hill.

layout some 120 feet below the lift hill.

Six: The vertical loop, which I’ve heard described as a bit of a dead moment, but if a vertical loop is considered a ‘let down’ then it’s a testament to the sheer insanity of the track that preceded it. I personally thing that this inversion is a logical successor to the previous stall turn and doesn’t let the ride down at all, continuing to hold the adrenaline levels at a consistent level not too far beneath that generated by the centerpiece barrel roll. It does go a little slow around the top but I see this as a benefit as I like my inversions to make me feel like I’m genuinely upside down, and very little achieves that better than an old-fashioned loop-de-loop.

Seven: The second stall turn. Okay, Nemesis had an excellent run of six maneuvers but here’s where it finally starts to sputter out of gas. After the vertical loop the train rushes through a short tunnel, a promising progression that leads to relatively little when it emerges to a long, slow turnaround over the midway, for the first time with plenty of clearance between legs and landscape. A little bit of back and forth banking trickery isn’t enough to save us from the fact that for the first time we’re consciously aware that the current element isn’t to the same standard of quality as the one preceding it. It could have been established as an ‘eye of the storm’ tactic that allows us to savor the moment’s tranquility before diving into an even more hellbending second half, but as we will see there’s not enough post-stall turn for this to work on repeat rides; instead it effectively signals the end of Nemesis’ main sequence we paid our admission and waited in line for, not that we’ll demand it end early. On any other coaster this would have been an acceptable pause, but Nemesis didn’t spend the first 2/3 of its layout establishing itself to be like any other coaster.

there’s not enough post-stall turn for this to work on repeat rides; instead it effectively signals the end of Nemesis’ main sequence we paid our admission and waited in line for, not that we’ll demand it end early. On any other coaster this would have been an acceptable pause, but Nemesis didn’t spend the first 2/3 of its layout establishing itself to be like any other coaster.

Eight: The final flatspin; this corkscrewing inversion again kicks major ass, carved along a narrow trench of land between two underground tunnels and a near-collision with the Mushroom Cloud Tour Bus, it’s much faster paced and inline than the first corkscrew and possibly the second meanest and grittiest moment of the layout after the helix/twist combo. However, it’s still just an isolated element sandwiched between two missed beats, and so the sense of rapidly increasing pacing and tempo between elements that made the main sequence so dynamic is also missing.

it’s still just an isolated element sandwiched between two missed beats, and so the sense of rapidly increasing pacing and tempo between elements that made the main sequence so dynamic is also missing.

Nine: Should I even count this as its own beat, or just conclude that the ride finished with the flatspin? There’s a final right hand turn under Air’s lift hill that abruptly transitions out into the brake run. Altogether nothing spectacular but still a part of the layout so it deserves some consideration.

the layout so it deserves some consideration.

Even if it falters a bit in its last three moments I’m still impressed by Nemesis through and through. Without question this would be considered a high point of nearly every career involved in this attraction. For myself, the principle question that I would wrestle with for some time was whether it would replace Raptor as my most favored B&M attraction. For a while I thought I would continue to give the nod to Raptor, appearances of home-park fanboyism be damned. The main thing that was leaving a bad taste in my mouth in regards to Nemesis was that it too fell victim to B&M’s inability to maintain pace and make the second half of the layout as good as the first. Granted, this wasn’t due to a boring or repetitive finale, just because the first half was so amazing that it would have taken a lot to pull this off. However, I do think that version of Nemesis could have existed, if the second stall turn had been kept underground at high speeds for the entire span from the vertical loop to the flat spin. Extending the final turn into a Raptor-like double helix (providing a bold positive-G punctuation) would have beyond question cemented Nemesis’ status as immortal legend, but given what I imagine would have already been difficult budget and planning constraints, the ride as it exists today is still something of a miracle to behold. (They probably could have lowered the second stall turn closer to the pathway, though, that would have improved it to very little if any additional expense.)

have taken a lot to pull this off. However, I do think that version of Nemesis could have existed, if the second stall turn had been kept underground at high speeds for the entire span from the vertical loop to the flat spin. Extending the final turn into a Raptor-like double helix (providing a bold positive-G punctuation) would have beyond question cemented Nemesis’ status as immortal legend, but given what I imagine would have already been difficult budget and planning constraints, the ride as it exists today is still something of a miracle to behold. (They probably could have lowered the second stall turn closer to the pathway, though, that would have improved it to very little if any additional expense.)

I realize that lamenting against these rather insignificant ‘dull’ moments may seem hypocritical when Raptor has many more slow or meandering parts to it, but the point is that Nemesis establishes itself as a ride that succeeds based on its no-holds-barred fury so every second that fails on this promise is a second that doesn’t belong. Raptor, on the other hand, I thought was much more artful in its progression, altering between the intense and the elegant, holding back just enough so that when it does dive in for the kill in the grand finale, every moment before seems in harmony with each other. Raptor had the substance that Nemesis’ short lift-to-brake ride time simply could not offer, especially in light of the relatively weak finale.

But after a month or two of thinking it over, I came to a logical conclusion: at least two-thirds of Nemesis is better than even the best part of Raptor. How can it possibly add up that Raptor is better if there are no moments that I’m as elated as on the best parts of Nemesis? Nemesis is the better roller coaster. It is one of the best roller coasters. Quod erat demonstrandum.

Thirteen is located in a themed area monikered the “Dark Forest”. Because Alton Towers is located on the 53rd degree of latitude where the summer sun doesn’t set until after 9:30pm and zoning and noise ordinances require that guests exit the park several hours before that time, not a single visitor during the peak season months will ever actually see a forest that is dark. This summarizes everything else there is to be said about the new-for-2010 roller coaster in a nutshell. Which is to say: Thirteen is a failure.

Much discourse has been had over Thirteen’s merits and shortcomings. After the initial debut generated a whirlwind of emotions from long-anxious fans, the dust soon settled to a consensus that Thirteen had been overhyped for thrill seekers and was in fact the tamest of the Tower’s headlining coaster. Then the dialectic swung in the opposite direction, with many voicing their support for the coaster as a return to form for Alton Towers and John Wardley, only to swing back with the observation that it was too short and failed to deliver on many of the aspirations the concept promised. A vague consensus was later reached that, if approached as a family ride, it’s actually a good, fun little coaster with some nice surprises along the way; even this statement is unlikely to go without controversy. If there was one clear consensus out of all of this, it seemed to be that one’s opinion of Thirteen was less dictated by the actual quality of the ride itself than it was by where one set their own expectations prior to boarding.

for thrill seekers and was in fact the tamest of the Tower’s headlining coaster. Then the dialectic swung in the opposite direction, with many voicing their support for the coaster as a return to form for Alton Towers and John Wardley, only to swing back with the observation that it was too short and failed to deliver on many of the aspirations the concept promised. A vague consensus was later reached that, if approached as a family ride, it’s actually a good, fun little coaster with some nice surprises along the way; even this statement is unlikely to go without controversy. If there was one clear consensus out of all of this, it seemed to be that one’s opinion of Thirteen was less dictated by the actual quality of the ride itself than it was by where one set their own expectations prior to boarding.

It’s perhaps unsurprising that so much of the discussion on Thirteen requires justifying expectations in light of the marketing campaign that surrounded it, which has possibly more notoriety than the attraction itself. Apparently Alton Towers’ marketing department never actually sat down with the rides designers to figure out what sort of attraction they would be promoting, or were unfamiliar with the general formula that says “happiness = reality / expectations”, or didn’t care when they launched one of the most shamelessly over-the-top hype campaigns that would make a snake oil salesman turn red with embarrassment. Most agree that the plan backfired when the ride failed to live up to expectations, unless they maintain that even bad publicity is good publicity; this would at least explain the sheer quantities of stupid publicity that I was told most Americans don’t understand the humor in. I’m sympathetic to the humorous dimensions but not when they did nothing to truly engage fans of the park, instead sitting back and giving everyone a big wink every couple weeks in reference to information that had already been leaked for months in the blueprints submitted to the town council while critics began attracting an ever-larger audience to their online podiums before an announcement had even been made. During this time I recall seeing a wireframe animation that showed the dropping mechanism raising the front of track up diagonally after the plunge so the train released backwards at a downhill angle (somewhat like if you merged it with a Vekoma Tilt Coaster). I thought, “Well, at least that’s cool enough to be worthy some of the hype,” but then it turned out that it was just a piece of fan art that was better than the official design. Some of Thirteen’s failures would have been evident regardless of if you approached it having lived in a cave during its development, but another part of it was simply because the idea was far bigger than the coaster itself.

unless they maintain that even bad publicity is good publicity; this would at least explain the sheer quantities of stupid publicity that I was told most Americans don’t understand the humor in. I’m sympathetic to the humorous dimensions but not when they did nothing to truly engage fans of the park, instead sitting back and giving everyone a big wink every couple weeks in reference to information that had already been leaked for months in the blueprints submitted to the town council while critics began attracting an ever-larger audience to their online podiums before an announcement had even been made. During this time I recall seeing a wireframe animation that showed the dropping mechanism raising the front of track up diagonally after the plunge so the train released backwards at a downhill angle (somewhat like if you merged it with a Vekoma Tilt Coaster). I thought, “Well, at least that’s cool enough to be worthy some of the hype,” but then it turned out that it was just a piece of fan art that was better than the official design. Some of Thirteen’s failures would have been evident regardless of if you approached it having lived in a cave during its development, but another part of it was simply because the idea was far bigger than the coaster itself.

Just to get this out of the way now, I enjoyed Thirteen. I realize that must sound blatantly contradictory after declaring Thirteen a failure a few paragraphs above. A ride can be fun but still considered a failure. Everything we encounter in day to day life automatically forms a like/dislike reaction, generally based on arbitrary psychological forces, after which we then try to use rationality to justify these opinions (that sums up this website pretty well). Although given the high degree of intersubjective agreement between riders who all disembark with claims of having had fun, such a reaction is unlikely to be wholly arbitrary. Thus, ignoring as much as I can the presupposed opinions I had before I even arrived in Alton Towers, here’s the very first ride I experienced:

We had to wait over ninety minutes in the queue, which may have been a good time to generate eagerness and/or apprehension over the ride to come but most of the queue is away from the ride in a simple wooden corral. The last indoor ‘themed’ section of the queue is rather brief, a large tesla coil inside that never activated when we went by. The station area is rather square and boxy with a lot of scaffolding on the outside, I couldn’t tell how much of this look was deliberate or not. On the plus side, three 5-car trains cycle through with rapid efficiency every minute or so (thanks to the elimination of all seatbelts and a simple lapbar in a roomy, standard sit-down vehicle) so hopefully once the excitement as the big new ride wears out it will become the most easily accessible and reridable roller coaster in the park. This was also aided by a nice loose items system, which are collected in a free bin just before reaching the station platform, receiving a rubber wrist band with a number on it to recollect your items at the opposing window along the exit ramp, although the biggest downside is chavs have a tendency to cut behind you while you’re handing your stuff over.

Electing the front seat as the mandatory first ride experience (they assign seats but are lenient towards requests, especially if you’re accompanied by a local who’s friends with the attendant on duty) the train is quickly (too quickly?) loaded, checked and dispatched. We immediately enter the bright daylight, making a small dip around a wide left turn in a trench to approach the lift hill. This is possibly the quietest lift I’ve ever been on, the tire drive mechanisms chosen for that very quality (they even trigger in small ‘blocks’ as the train approaches and shut off as soon as we pass by so they aren’t unnecessarily wasting energy). It does appear more appropriate on a children’s attraction and I do wonder how tires render the anti-rollback mechanism dispensable when one would imagine them more susceptible to backwards slippage, but it gets the job done well. We crest the top of the 60 foot apex and we hang over the edge, us leading the plummet straight down with hands in the air.

would imagine them more susceptible to backwards slippage, but it gets the job done well. We crest the top of the 60 foot apex and we hang over the edge, us leading the plummet straight down with hands in the air.

“Hey, we’re on Intimidator 305!” I excitedly exclaim as the magnetic trim brakes grab at our vehicle on the entire length of the first drop, which leads into a ground-level, right-hand 270° turn and then up into an airtime camelback hill crossing the lift hill. I would later find out these trim brakes were added not because Thirteen was causing grey-outs and evaporating the wheels from the high G’s, but because the computers were getting their timing sequences thrown off when the vehicles were clocking in faster than expected. (facepalm.) Somehow I don’t believe that older, ‘technologically inferior’ roller coasters would have ever even had the imagination to use that as a reason to neuter their guest experience.

brakes were added not because Thirteen was causing grey-outs and evaporating the wheels from the high G’s, but because the computers were getting their timing sequences thrown off when the vehicles were clocking in faster than expected. (facepalm.) Somehow I don’t believe that older, ‘technologically inferior’ roller coasters would have ever even had the imagination to use that as a reason to neuter their guest experience.

There’s a somewhat random series of hills and banked turns that follows, with aspirations to imitate a Mega-Lite in the woods (how awesome would that be?) but, either because of the trim brakes or just using a conservative design from the get-go, is almost completely forceless. The first airless hill leads into a second straight, airless bunny hill, into a slightly more interesting-to-look-at banked non-airtime crest, a little switchback near ground level that leads into a much more heavily banked switchback over a larger hill, which maybe gets some nice back-and-forth dynamics going if it didn’t nearly run out of momentum at the top. This actually generates the most significant force on the ride, as we travel so slow out of this curve that there’s not nearly enough

in the woods (how awesome would that be?) but, either because of the trim brakes or just using a conservative design from the get-go, is almost completely forceless. The first airless hill leads into a second straight, airless bunny hill, into a slightly more interesting-to-look-at banked non-airtime crest, a little switchback near ground level that leads into a much more heavily banked switchback over a larger hill, which maybe gets some nice back-and-forth dynamics going if it didn’t nearly run out of momentum at the top. This actually generates the most significant force on the ride, as we travel so slow out of this curve that there’s not nearly enough

centripetal force to keep us firm in our seats and so we all tend to fall out towards the left side of the train. One last little curve and we’re led into a second tire drive lift hill (although it’s so short and the tires kick fast enough that it feels little more than an extended midcourse brake). The forest is also sparser than I thought the tree huggers on Alton’s council would have allowed, as there were none of the near-hit tree branches that a ride carefully designed to prevent the removal of

centripetal force to keep us firm in our seats and so we all tend to fall out towards the left side of the train. One last little curve and we’re led into a second tire drive lift hill (although it’s so short and the tires kick fast enough that it feels little more than an extended midcourse brake). The forest is also sparser than I thought the tree huggers on Alton’s council would have allowed, as there were none of the near-hit tree branches that a ride carefully designed to prevent the removal of as many trees as possible would have had.

as many trees as possible would have had.

We enter the ‘crypt’, where the big surprise that everyone knew about awaited us. The tires waste no time in moving us directly into position on the drop track. The room is fairly barren with some scaffolding and work lights on the walls, and a dead end directly in front of us. Unlike on Oblivion, where they hold you for as long as they can to generate the suspense, Thirteen’s drop surprises because it launches so quickly after we come to a final stop. I would have expected some sort of dark ride show, but instead the door just closes behind us as soon as we pass through, you hear some wooden creaking for a second or two, and then the ride drops.

I’m not sure if a spoiler warning will be useful to many at this point in Thirteen’s history, but there are one or two things that were still small surprises to me that I wouldn’t have liked to have had revealed prematurely, so if you find yourself in the same circumstance, skip the rest of this paragraph, and maybe the one after it, too (I know some people are really gung-ho about their spoiler warnings). There’s a fake-out drop of a few inches accompanied by a blast of compressed air; the first time I rode I couldn’t tell if we had fallen or if it was just the air that I felt, on later rides farther away from the air canons I could indeed tell there was a downward jolt of about two inches. The elevator then drops the remaining distance in pure freefall, by far the most thrilling part of the coaster so far. The lower crypt level appears much like the upper, but with more ominous, green lighting and the stone statue replaced with a ‘real’ wraith, the scaffolding also now filled with wraiths. So the curse has come true, very Hex-esque. It’s a nice little bit of atmosphere change for the second or two that it lasts. The other surprise was the launch backwards out of the lower crypt (not too fast, mind, but hastier than a normal tire drive transport section), which again takes place in a very brief amount of time. Surely it’s an engineering feat to get clearance to launch barely a second after landing but does it make theatrical sense? I guess the absence of enough time to soak in the details allows for an ‘impressionistic’ memory of the crypt.

by far the most thrilling part of the coaster so far. The lower crypt level appears much like the upper, but with more ominous, green lighting and the stone statue replaced with a ‘real’ wraith, the scaffolding also now filled with wraiths. So the curse has come true, very Hex-esque. It’s a nice little bit of atmosphere change for the second or two that it lasts. The other surprise was the launch backwards out of the lower crypt (not too fast, mind, but hastier than a normal tire drive transport section), which again takes place in a very brief amount of time. Surely it’s an engineering feat to get clearance to launch barely a second after landing but does it make theatrical sense? I guess the absence of enough time to soak in the details allows for an ‘impressionistic’ memory of the crypt.

My favorite part was the backwards helix in the tunnel; for one thing, it really is dark in there. Normally there’s always something that catches my eye (small gaps in the seams of the walls or a sensor light) but any light rays still bouncing around in this tunnel were beyond the scope of my retinas to detect, and this lasts for several long seconds. There’s also a wavy back-and-forth motion to the track that, combined with the darkness, caused me serious consternation over how it was achieved. Was the banking pitch tipping in and out, was the helix rising and falling over small moguls, or was the radius an uneven ‘octagon’ shape? I could not be sure.

We exit the tunnel, finishing the last part of the curve and come to a stop just past the transfer track. It switches, and then we get a final ‘surprise’ tire launch rush back to the station, where the train ahead of us is efficiently clearing out of the station. Ahh… that was, indeed, fun. At the risk of becoming redundant, I would like to confirm that the other reviewers are correct: it’s no ultimate thrill ride but it is an enjoyable splash, and unique in Alton Towers’ catalog as their first progressively structured, multi-part roller coaster. I think it will probably mature nicely with the park once its appearance becomes more worn, the forest begins to reclaim some of the cleared out construction site, and its identity firmly becomes that of the imaginative family mine train with a unique ending and unusual theme that you can always count on to have the shortest queue in the park of the big coasters.

curve and come to a stop just past the transfer track. It switches, and then we get a final ‘surprise’ tire launch rush back to the station, where the train ahead of us is efficiently clearing out of the station. Ahh… that was, indeed, fun. At the risk of becoming redundant, I would like to confirm that the other reviewers are correct: it’s no ultimate thrill ride but it is an enjoyable splash, and unique in Alton Towers’ catalog as their first progressively structured, multi-part roller coaster. I think it will probably mature nicely with the park once its appearance becomes more worn, the forest begins to reclaim some of the cleared out construction site, and its identity firmly becomes that of the imaginative family mine train with a unique ending and unusual theme that you can always count on to have the shortest queue in the park of the big coasters.

And yet, I still have the issue of mentioning the F-word at the beginning of the review which to this point remains unresolved. Despite the faux-controversial significance that statement might incite, I don’t find calling Thirteen a failure to be all that interesting or even that important in my overall impression of the ride, and as indicated in the paragraphs above had little effect on my personal enjoyment of the ride. What I’m much more intrigued by is in the way that it failed, not by the usual route of being an uninspired or unimaginative concept, but because it had too much imaginative concept that wasn’t grounded in the reality of its situation. I think most people involved genuinely wanted to accomplish something special and unique with this ride, and observing why that didn’t happen could be just as important as if it did live up to their expectations.

I don’t think this is entirely an issue of Thirteen failing to meet expectations, because as it’s already been shown that when defined this way the resolution comes from changing expectations rather than changing the ride. I still believe there’s an absolute scale to the quality of a work that cannot be adjusted in any direction we wish simply by changing the way the viewer approaches that work; in other words, a work can be a failure from as early as the conceptual level. And furthermore, simply ‘liking’ a work might not be enough to prevent failure, provided we believe that a creative work has the power to accomplish something more than ‘merely’ entertainment (distant sounds of the slightly elitist-timbred drum beat of “Coasters Are [or could be] Art”).

Sifting through all the exaggerated marketing claims, one thing that caught my eye was the proclamation that this was to be “the world’s first psychoaster”. Never minding a near identical claim made by Universal back in 2004, this phrase struck me as coming from someplace deeper than the astronomical promises made, likely an idea from one of the few dialogues marketing director Morwenna Angove had with the creative heads of the project Candy Holland and John Wardley, whom I can imagine saying something to the effect of, “this ride will have a theatrical and dramatic element to it that will allow us to use psychology to manipulate passenger’s emotions even when they are standing still.” This sounds like a wonderful proposal, one that furthers the experimentation with new ways to craft rider’s subjective on-ride viewpoints that led to some successes with the vertigo/anxiety inducing Oblivion and freeform aesthetic nuance of Air by digging straight into the messy psychological mechanics that most ride engineers schooled in physics and mathematics are reluctant to fully acknowledge as being a vital component to their work. So why doesn’t it work?

We first run into the (admittedly rather pedantic) problem with the coaster’s name, Thirteen (or “Th13teen”, depending on how much of a nerd you are), which I cannot in good conscious accept as anything other than the results of a poorly run focus group that recommended it based on the average maturity level of the tossers who would frequent this attraction. As a noun it lacks concreteness, and it’s never clear if the first thing we should associate with the term is a superstitious roller coaster or any of the other thousands of uses numbers play in our daily life. I understand there’s supposed to be an intangible mystique surrounding the theme, but there are still so many better options out there to choose from. “Surrender”, for one, at least is a verb that allows for the vagueness of application that doesn’t work as well with a hard object reference noun. Or, if we want a noun that captures the essence of that unnerving (but also alluring) feel of being alone in the woods at night, the Germans already have a name contained in a single word: “Waldeinsamkeit”. Okay, the marketing department would probably be foaming at the mouth if they had to try to sell that pronunciation on print and media, but my philosophy when it comes to naming things is that the more difficult it is to remember, the more difficult it is to forget.

of uses numbers play in our daily life. I understand there’s supposed to be an intangible mystique surrounding the theme, but there are still so many better options out there to choose from. “Surrender”, for one, at least is a verb that allows for the vagueness of application that doesn’t work as well with a hard object reference noun. Or, if we want a noun that captures the essence of that unnerving (but also alluring) feel of being alone in the woods at night, the Germans already have a name contained in a single word: “Waldeinsamkeit”. Okay, the marketing department would probably be foaming at the mouth if they had to try to sell that pronunciation on print and media, but my philosophy when it comes to naming things is that the more difficult it is to remember, the more difficult it is to forget.

But we can be more audacious than that. Imagine this: The 2010 roller coaster’s announcement comes with a fancy webpage and announcement ceremony, but there are no direct references to the ride’s name. Questions are asked regarding this detail and they just refer to the ride in generic terms. Probably they’re still formulating that or they may announce a ‘name the coaster’ contest at a later date. Weeks go by and still nothing to call the hotly anticipated attraction by. Maybe they’re saving it for the official debut, as part of whatever the big surprise in the crypt is? It opens, and an elaborately haunting entryway can’t conceal the fact that no signage beyond the normal safety and height markers can be found anywhere. All the guides and brochures refer to it as “our newest roller coaster”, “Alton Tower’s eighth roller coaster”, “the ride in the Dark Forest”. Online debate rages over what to call it. Some call it “The 8th Roller Coaster” or “The Dark Forest Roller Coaster” because that’s the closest the park has ever come to naming it. Others say it should be “Intamin Family Roller Coaster” because that’s what it said on one of the shipment plates. Many call it “Unknown” because that’s how it’s still filed under the RCDb. But the rest merely murmur “that ride”, the one in the back of the park whose name cannot be uttered. Everyone knows what it is and what it looks like, yet this knowledge becomes strangely alienating because there’s no common communal label that can automatically identify this amalgamation of feelings and fears we have of this ride in our minds when discussing it with others. I think my “that ride” means the same thing to me as it does to you, but how can we ever be sure?

But we can be more audacious than that. Imagine this: The 2010 roller coaster’s announcement comes with a fancy webpage and announcement ceremony, but there are no direct references to the ride’s name. Questions are asked regarding this detail and they just refer to the ride in generic terms. Probably they’re still formulating that or they may announce a ‘name the coaster’ contest at a later date. Weeks go by and still nothing to call the hotly anticipated attraction by. Maybe they’re saving it for the official debut, as part of whatever the big surprise in the crypt is? It opens, and an elaborately haunting entryway can’t conceal the fact that no signage beyond the normal safety and height markers can be found anywhere. All the guides and brochures refer to it as “our newest roller coaster”, “Alton Tower’s eighth roller coaster”, “the ride in the Dark Forest”. Online debate rages over what to call it. Some call it “The 8th Roller Coaster” or “The Dark Forest Roller Coaster” because that’s the closest the park has ever come to naming it. Others say it should be “Intamin Family Roller Coaster” because that’s what it said on one of the shipment plates. Many call it “Unknown” because that’s how it’s still filed under the RCDb. But the rest merely murmur “that ride”, the one in the back of the park whose name cannot be uttered. Everyone knows what it is and what it looks like, yet this knowledge becomes strangely alienating because there’s no common communal label that can automatically identify this amalgamation of feelings and fears we have of this ride in our minds when discussing it with others. I think my “that ride” means the same thing to me as it does to you, but how can we ever be sure?

A press release described Thirteen as “combining elements of physical and psychological thrills,” which seems to indicate that they regard these are completely separate elements. At first this may sound reasonable, but unpack it a little bit and you come up against a hard barrier. Namely, what’s the difference between the two? It seems to want us to associate objectivity with one and subjectivity with the other, but then you’d be making the mistake of the naïve realist and claiming that some things we have direct knowledgeable access to, that circumvents the subjectivity of our sensation-based perspectives. Besides, I don’t see how the drop track isn’t categorized as a physical thrill anyway. Ah, but “psychological thrills” means thinking about things that have not yet happened, rather than responding to that which already has!

between the two? It seems to want us to associate objectivity with one and subjectivity with the other, but then you’d be making the mistake of the naïve realist and claiming that some things we have direct knowledgeable access to, that circumvents the subjectivity of our sensation-based perspectives. Besides, I don’t see how the drop track isn’t categorized as a physical thrill anyway. Ah, but “psychological thrills” means thinking about things that have not yet happened, rather than responding to that which already has!

That almost makes sense… but if that’s the definition we want to use, then Thirteen utterly fails. Apart from the absence of any drama or theatrics anywhere throughout the ride’s presentation, Wardley himself has claimed that the whole ‘psychological’ aspect of the ride was supposed to remain a complete surprise (hence Tony Adkins). But how can there possibly be any psychological element involved if we don’t know what’s coming and therefore can’t think about it before hand? Unless you use a really weak definition of the word to simply include any form of surprise, which would necessarily also posit today’s stupid shock-horror teen movies as “psychologically challenging”, and even I’m not that jaded towards the potential of pop-culture. And even if we were, it still can’t be considered a world’s first because there are plenty of other thrill rides throughout history that have had a moment of surprise hidden along their course. Fixating on the drop alone isn’t getting us anywhere; let’s look at the draaaaaama that leads up to it.

‘psychological’ aspect of the ride was supposed to remain a complete surprise (hence Tony Adkins). But how can there possibly be any psychological element involved if we don’t know what’s coming and therefore can’t think about it before hand? Unless you use a really weak definition of the word to simply include any form of surprise, which would necessarily also posit today’s stupid shock-horror teen movies as “psychologically challenging”, and even I’m not that jaded towards the potential of pop-culture. And even if we were, it still can’t be considered a world’s first because there are plenty of other thrill rides throughout history that have had a moment of surprise hidden along their course. Fixating on the drop alone isn’t getting us anywhere; let’s look at the draaaaaama that leads up to it.

At first Thirteen seemed to be on the right track, with an emphasis on mystery and darkness to provide a suitably chilling atmosphere. I am certainly in agreement with Wardley when he says that for most amusement attractions the story is wasted on the majority of guests, as the emotional connection is dependent upon finding those states of awareness that are always real (i.e. one’s awareness and orientation towards time, anxiety towards a particular end, the pure visual sensation of complete darkness), while literal storytelling requires a fictitious relationship with guests. Now, in the case of Thirteen the theatrical elements could still be put to great effect provided they’re used ambiguously enough remain metaphors for those real experiences. This actually works quite wonderfully with the technology, as the drop track into the dark seems to be the perfect embodiment of our fear of death… which at a fundamental level is what all roller coasters are really about, right?

At first Thirteen seemed to be on the right track, with an emphasis on mystery and darkness to provide a suitably chilling atmosphere. I am certainly in agreement with Wardley when he says that for most amusement attractions the story is wasted on the majority of guests, as the emotional connection is dependent upon finding those states of awareness that are always real (i.e. one’s awareness and orientation towards time, anxiety towards a particular end, the pure visual sensation of complete darkness), while literal storytelling requires a fictitious relationship with guests. Now, in the case of Thirteen the theatrical elements could still be put to great effect provided they’re used ambiguously enough remain metaphors for those real experiences. This actually works quite wonderfully with the technology, as the drop track into the dark seems to be the perfect embodiment of our fear of death… which at a fundamental level is what all roller coasters are really about, right?

Then why is it that the dramatic storytelling is so curiously minimized in Thirteen? It seems in the interests of maximizing capacity the attraction has a rather sterile, utilitarian aura to it that seems to conflict with the dark, brooding theme. There’s almost no backstory presented in the queue (a few half-baked items of junk ‘reclaimed by the forest’ but not enough to establish the right tonal connection with patrons who probably have other things on their mind), the time spent in the station house to take in the atmosphere is almost negligible (and the dark and gloomy interior just creates cognitive dissonance with the bright daylight outside), the time it takes to go from sitting down to cresting the lift must be less than a third that of the other coasters (was any attempt made to engage our psyches before sending us on “just another roller coaster ride”?), and the entire drop sequence barely registers as much different from any other coaster with a big midcourse drop (the timing and sensation is about the same as on the new B&M dive coasters, so I’m not sure how this drop is differentiated as being “psychological” just because the technology is different and you’re in the dark).

brooding theme. There’s almost no backstory presented in the queue (a few half-baked items of junk ‘reclaimed by the forest’ but not enough to establish the right tonal connection with patrons who probably have other things on their mind), the time spent in the station house to take in the atmosphere is almost negligible (and the dark and gloomy interior just creates cognitive dissonance with the bright daylight outside), the time it takes to go from sitting down to cresting the lift must be less than a third that of the other coasters (was any attempt made to engage our psyches before sending us on “just another roller coaster ride”?), and the entire drop sequence barely registers as much different from any other coaster with a big midcourse drop (the timing and sensation is about the same as on the new B&M dive coasters, so I’m not sure how this drop is differentiated as being “psychological” just because the technology is different and you’re in the dark).

Slowing down the first turn to the lift hill and adding a showroom to it would have been enough to generate some feeling of suspense to initiate the ride before blasting riders dazed back into the sunlight to start what otherwise appears to be just another normal roller coaster. An onboard soundtrack would have been able to add weight to the necessary emotional cues and lend the rather disjointed first and second halves of the layout greater coherence. And even though I sort of mocked it in part one, a preshow similar to Hex’s would have worked wonders before Thirteen. Simply before letting them into the final queue zone, you hold guests back in a room similar to those Six Flags used on the Dark Knight coasters, and then you just tell a simple fable that doesn’t force a story unnaturally upon them but gives them time to reflect on the significance of the ride ahead of them while establishing a proper atmosphere and providing few humanist themes to give the arty intellectual snobs something to regard. Here’s just one possible story:

Long ago a princess awoke from a dream in which she heard an old woman whispering in her ear, “Do not fear the unknown. Your destiny awaits you in the dark forest.” The sound of the voice echoed inside her mind for weeks, and eventually decided to ask her father the king what this could possibly mean. He assured her that there was no reason for her to be afraid, as she was the princess and therefore was safe from any such harm. Nevertheless, he warned her against entering the dark forest.

One day her puppy when running off into the woods behind her castle while they were playing, and so she reluctantly went off alone in search of him. She eventually found him with an old crone sitting on a rotted log. As the lady spoke to her she realized the voice was the same as in her dream. “Welcome, my child, we’ve been expecting you.” At that moment several wraiths appeared, watching her silently through the trees. “Who are you? What do you want from me?” the princess nervously enquired.

“Do not be afraid,” said the old lady, “we are but merely your fate. Many have come before you and many have yet to come.” She indicated one of the wraiths. “One day, one of my sisters will come to collect your soul. There is no pain or humility involved, and you are allowed to decide when and in what form my sister will greet you in. Take as long as you need, and in the meantime go back to your home and lead a prosperous life.”

“But no, you are mistaken,” said the princess. “I was not supposed to come here. As the princess I am protected from my fate. It was never my choice to meet you.”

“My dear,” laughed the crone, “What makes you think you are so special that you can avoid the inevitable? A silly crown? There is only choice that is yours to make: you may accept today your fate and decide its form so when the time comes you are prepared; or you may leave in blissful ignorance, falsely believing for the rest of your life that you are the exception to fate, only to be surprised when we arrive in a form you were not expecting.”

The princess thought long and hard before she made her decision. After it was made she bid farewell to the crone and her sisters, and returned home just before nightfall. As she fell asleep that night, she wondered how she could face her next day in the comfort of her castle.

Okay, so maybe that’s a bit long-winded and pretentious but it’s just to give an example of how a simple narrative can provide to set the right tone for a ride experience. Obviously I devised this story to provide a means to interpret the roller coaster in an existential light as a metaphor for being-towards-death (the ‘unknown’ drop track), freewill (it is our choice that has brought us to ride), and fatalism (once strapped in there’s no avoiding the inevitable). The ambition of all of this is to find new ways to transcend the boundaries of how riders encounter themed entertainment so that some, even if only a minority, will have the pleasure of discovering something uniquely artistic about the attraction. It doesn’t have to be the world’s ultimate thrill ride to be a success just as long as the experiment results in something new.

Granted, even with all these bullshit dramatic suggestions, that artistry would only be achieved by pasting pre-existing theatrical, musical or cinematic aesthetics over a thrill ride that remains fundamentally no different from any other rather than developing the roller coaster as its own artistic canon with unique aesthetic properties. But the narrative I’ve been crafting for nearly two years on these web pages has since its inception been alluding to the industry’s movement in that direction, and Thirteen was one of the few rides I can think of where those ambitions were more explicitly stated. Yet the ride that I found not only failed to achieve any psychological ambitions, it seems as though it didn’t even try; whatever enjoyment I did derive being precisely equal to the sum of its “physical thrill” parts. Rides like Oblivion, Air and Hex, for whatever their flaws, at least had an ideal in mind and the physical hardware in place would be a working demonstration of that ideal. Thirteen started the same way, yet missed its mark so completely that one would have to look elsewhere for an example of even a bad “psychoaster”.

The final irony of all this revisionist criticism is that Thirteen was still quite possibly as good as the ride could have been within its broad conceptual outline. Everything I suggested in the preceding paragraphs I am quite confident were not beyond the creative scope of the development team (quite hopefully there was much more discussed that I never even thought of), but was shelved due to tremendous restrictions bordering all sides of the project. A preshow room or a dark ride enclosure of portions of low-speed track would have both required expanding the footprint of the station structure, an action that would have required additional building permits that are unlikely to be granted. In the showdown between an onboard soundtrack and local noise ordinances, guess which one would win? Is the outdoor layout through the woods too short? We should consider ourselves lucky to have gotten it at all. Even if a few of these items could have won approval from the city council, they almost surely would have been halted at the next step of getting approval from Merlin, whom I’m guessing would have been watching every pence that went over their £15 million budget to get a ‘world’s first’ element. Thirteen is a recession-era ride, after all, quite different from the Go-Go Nineties when they had the financial wherewithal capable of reshaping the planet to get Nemesis and Oblivion to fit within bounds.

This doesn’t quite excuse Thirteen. This all goes back to the very beginning, about why one would choose to theme a ride to the “Dark Forest” when the forest would never actually be dark. It’s certainly no one’s fault that the proper outdoor lighting (or lack thereof) would be forever untenable given the length of a summer day and the restrictions against late-night communal disturbances. Yet they still decided to call it the Dark Forest. It’s not their responsibility to perform tasks that rest beyond the reach of practicality just to please the fan’s extravagant expectations, but it is their responsibility to know where those limitations are so visitors aren’t left feeling like they were encouraged to make those high expectations only to be revealed a ride that’s an empty promise. Perhaps in the perfect world there would have been philosophical preshows, long eerie corridors of the industry’s most exquisite thematic design, a sinister soundtrack that grips us with icy fear as we rampage all the way down the valley, slowing down just long enough for us to consider our fates before a Tower of Terror-esque sequence in an abandoned, burnt-out cathedral leads to a 100 foot vertical plunge, culminating in a transcendental climax of being shot backwards at 50 miles per hour through a quarter mile tunnel in the black abyss of the nether realm. But all of that clearly would have been impossible. Rather than formulate new plans that would have fit without compromise within the necessary limitations, we got a compromised version of the ideal; and so thoroughly compromised that the ideal could no longer stand on its own legs. The result was that the fans had to be the ones pay for the gulf between the vision and the reality; they could either bridge the missing parts with their own imagination, forcing themselves to believe that deeper emotional reactions were authentic which the overambitious experience could not provide… or they could pretend that the lofty vision had never even been there at all. I’m not sure which is worse.

Next: Drayton Manor

Previous: Alton Towers (Part 1)

(Credit for all interior and backstage photos of Thirteen to Timothy Cox. Used with permission.)

Comments