It took me long enough, but I finally made it to the Magic Kingdom. I’ve been to Disneyland in California, Disneyland Paris, Tokyo Disneyland, and even held a season pass for Hong Kong Disneyland, but somehow it took until 2012 to check off my list the most popular theme park in the world, even though it’s the only Disney resort located in the same time zone as my hometown. My Magic Kingdom abstinence even turned into something I was oddly proud of, since there was nothing unique to claim from being counted among the millions of Disney World customers that can make the hobby of tracking down obscure parks and coasters so addictive, but I could claim something unique about the chronology through which I would eventually visit the parks. Before taking off for Florida I joked that being a theme park critic and having never been to the Magic Kingdom is a bit like being a film critic and having never seen Star Wars. It was finally time that I rectified this oversight. And now that I have, this begs the question: how does the Magic Kingdom fare against its counterparts, and did it serve as a suitable finale to my two-and-a-half year, round-the-world tour of Disney parks and resorts?

To answer: not that well; and no, I visited the Disney parks in the opposite order I probably should have. This isn’t to say that the Magic Kingdom is a bad park, or even bad for a Disney park. It’s probably the best overall introduction for newcomers to the (Not-Always) Wonderful World of Disney. It summarizes the best aspects of each of the Disneylands in Anaheim, Tokyo, Paris, and Hong Kong, without actually doing better in any category than what each of those other parks specializes in. Anaheim has the best overall collection of rides, Paris has the most detailed and beautiful landscapes, Tokyo has a scale and tech advantage in many of its attractions and entertainment, Hong Kong has much more intimacy and (more recently) originality, and the Magic Kingdom has…? Truth be told I had a hard time coming up with any aspect of the Magic Kingdom that I liked more than at any of the other parks, and the short list that I could manage are only the exceptions that prove the rule. It might have the best Haunted Mansion version in the world, although this win is slight in comparison to the landslide victories that Anaheim’s Pirates of the Caribbean, Tokyo’s Splash Mountain, or Paris’ Big Thunder Mountain have over the Floridian versions (among many others). The Carousel

To answer: not that well; and no, I visited the Disney parks in the opposite order I probably should have. This isn’t to say that the Magic Kingdom is a bad park, or even bad for a Disney park. It’s probably the best overall introduction for newcomers to the (Not-Always) Wonderful World of Disney. It summarizes the best aspects of each of the Disneylands in Anaheim, Tokyo, Paris, and Hong Kong, without actually doing better in any category than what each of those other parks specializes in. Anaheim has the best overall collection of rides, Paris has the most detailed and beautiful landscapes, Tokyo has a scale and tech advantage in many of its attractions and entertainment, Hong Kong has much more intimacy and (more recently) originality, and the Magic Kingdom has…? Truth be told I had a hard time coming up with any aspect of the Magic Kingdom that I liked more than at any of the other parks, and the short list that I could manage are only the exceptions that prove the rule. It might have the best Haunted Mansion version in the world, although this win is slight in comparison to the landslide victories that Anaheim’s Pirates of the Caribbean, Tokyo’s Splash Mountain, or Paris’ Big Thunder Mountain have over the Floridian versions (among many others). The Carousel of Progress, PeopleMover, and Country Bear Jamboree are three charming curios from an earlier era that can no longer be found at Disneyland, and thus are some of the only “Only in Florida” attractions that the Kingdom can lay claim to. (Tokyo also has a Jamboree, but that’s the better version only if your first language is Japanese.) And I suppose there will be a few good things to say about the additions in New Fantasyland once that’s completed, however I didn’t find the dress rehearsal that fantastic, and Shanghai Disneyland might very well steal the land’s thunder in a couple of years anyway.

of Progress, PeopleMover, and Country Bear Jamboree are three charming curios from an earlier era that can no longer be found at Disneyland, and thus are some of the only “Only in Florida” attractions that the Kingdom can lay claim to. (Tokyo also has a Jamboree, but that’s the better version only if your first language is Japanese.) And I suppose there will be a few good things to say about the additions in New Fantasyland once that’s completed, however I didn’t find the dress rehearsal that fantastic, and Shanghai Disneyland might very well steal the land’s thunder in a couple of years anyway.

Come to think of it, the biggest distinguishing characteristic that sets the Magic Kingdom apart from other theme parks is located outside the park boundaries. To reach the front gates from either the parking lot or Ticket & Transportation Center you have to cross the Seven Seas Lagoon by ferryboat. The intended effect of this nautical journey is most likely to create a sense of removal from the outside world by crossing over a (meta)physical barrier into a separate magical realm. Disney’s design philosophy has long placed tremendous value on barriers and gateways, for the way that they help us realize the exact point at which we change cognitive paradigms. Possibly the most famous is the railway tunnel separating the ticket booths and Main Street, U.S.A. with a plaque indicating “Here you leave today and enter the world of yesterday, tomorrow, and fantasy”, but you’ll also notice tunnels, bridges, special doorways, or bodies of water in the queues or at the start of the layout of most attractions in the park. The Seven Seas Lagoon ferry ride is by far the largest scale example of this design theory put into practice at a Disney park, making it a perfect example of how important this feature is to Disney’s design philosophy, especially since the ferry ride comes at the expense of the practicality. Arriving early in the morning a half hour before the gates are set to open while the mist is still hovering above the water’s surface: that’s Disney magic, and it’s achieved just through placement and timing, without needing any expensive themed props to dress it up. Trying to get back to the TTC after a long, tiring day and ten minutes before the bus is scheduled to depart: that’s Disney frustration, the kind that has given many stand-up comedians fodder for a routine about the toils and contradictions of taking the family on vacation.

famous is the railway tunnel separating the ticket booths and Main Street, U.S.A. with a plaque indicating “Here you leave today and enter the world of yesterday, tomorrow, and fantasy”, but you’ll also notice tunnels, bridges, special doorways, or bodies of water in the queues or at the start of the layout of most attractions in the park. The Seven Seas Lagoon ferry ride is by far the largest scale example of this design theory put into practice at a Disney park, making it a perfect example of how important this feature is to Disney’s design philosophy, especially since the ferry ride comes at the expense of the practicality. Arriving early in the morning a half hour before the gates are set to open while the mist is still hovering above the water’s surface: that’s Disney magic, and it’s achieved just through placement and timing, without needing any expensive themed props to dress it up. Trying to get back to the TTC after a long, tiring day and ten minutes before the bus is scheduled to depart: that’s Disney frustration, the kind that has given many stand-up comedians fodder for a routine about the toils and contradictions of taking the family on vacation.

Yet there’s no denying that, for whatever its faults (and there are many), the Magic Kingdom is a cultural experience of nearly unrivaled magnitude. It singularly reassures more people than anywhere else in the world that the American dream can come true, and it’s nothing if not fascinating to watch others have a minor spiritual revelation in the presence of such sublime kitsch. While people used to travel just to see the image of the Madonna, or even as recently as a film society screening of Carl Theodor Dreyer’s “La passion de Jeanne d’Arc” before the introduction of VHS, now theme parks like the Magic Kingdom fill the role of the irreplicable work of art that becomes a pilgrimage site for the masses. Immersing an audience for twelve consecutive hours in an environment where every perception is controlled by the artist is a degree of creative control that the avant-gardes of the 1920’s could only fantasize about, and especially as other media become increasingly digitized and oversaturated in their channels of mass distribution, in the coming decades the Magic Kingdom could become one of the last vestiges of society where the artist’s message is received as a postmodern “holy experience.”

Yet there’s no denying that, for whatever its faults (and there are many), the Magic Kingdom is a cultural experience of nearly unrivaled magnitude. It singularly reassures more people than anywhere else in the world that the American dream can come true, and it’s nothing if not fascinating to watch others have a minor spiritual revelation in the presence of such sublime kitsch. While people used to travel just to see the image of the Madonna, or even as recently as a film society screening of Carl Theodor Dreyer’s “La passion de Jeanne d’Arc” before the introduction of VHS, now theme parks like the Magic Kingdom fill the role of the irreplicable work of art that becomes a pilgrimage site for the masses. Immersing an audience for twelve consecutive hours in an environment where every perception is controlled by the artist is a degree of creative control that the avant-gardes of the 1920’s could only fantasize about, and especially as other media become increasingly digitized and oversaturated in their channels of mass distribution, in the coming decades the Magic Kingdom could become one of the last vestiges of society where the artist’s message is received as a postmodern “holy experience.”

Main Street, U.S.A.

Main Street, U.S.A.

The “opening credits” for the Magic Kingdom are found in Main Street U.S.A. Literally. The names painted on the second floor windows are all for Disney Imagineers, although I was too thick to notice this until I read about it after I returned home. The concept of public authorship is strangely absent from theme parks when compared to other creative arts and entertainments,1 so I appreciate the effort Disney puts into it even though their idea of title cards is still my idea of Easter Eggs for fans. I suspect this goes back to the distinction between art and hyperreality. If we recognize something as art we demand that an artist is presented along with it (even if that name is unrecognized to us; “who directed this”, “who painted that”, etc), but a hyperreal theme park environment demands that its makers remain hidden behind the curtain of conscious thought, lest the illusion of hyperreality is destroyed. Thus I think Main Street is probably better categorized as the “prologue” or “introduction” to the Magic Kingdom. It’s the “once upon a time” origins story for Disney: a familiar everyday setting (although still a little fantastical) which inspires the daydreams of the fantastical worlds we’re about to springboard off to, either by foot or by train. That, and it’s also where you can go to eat and buy stuff you probably shouldn’t eat or buy, at least not during

this goes back to the distinction between art and hyperreality. If we recognize something as art we demand that an artist is presented along with it (even if that name is unrecognized to us; “who directed this”, “who painted that”, etc), but a hyperreal theme park environment demands that its makers remain hidden behind the curtain of conscious thought, lest the illusion of hyperreality is destroyed. Thus I think Main Street is probably better categorized as the “prologue” or “introduction” to the Magic Kingdom. It’s the “once upon a time” origins story for Disney: a familiar everyday setting (although still a little fantastical) which inspires the daydreams of the fantastical worlds we’re about to springboard off to, either by foot or by train. That, and it’s also where you can go to eat and buy stuff you probably shouldn’t eat or buy, at least not during this economic recession. This is now the fifth Disney Main Street (or equivalent) that I’ve briskly walked through on my way to better things. Sure, once the afternoon crowds fill in I’ll return to fulfill the geek’s duty to look at all the detail, but after a half hour I still can’t find very much that isn’t cover-up for a gift shop. I’ll take the next train that comes in, going clockwise around the park for the rest of the review. Just as Main Street is the prologue, Tomorrowland is definitely supposed to be the final act before the curtain call, right?

this economic recession. This is now the fifth Disney Main Street (or equivalent) that I’ve briskly walked through on my way to better things. Sure, once the afternoon crowds fill in I’ll return to fulfill the geek’s duty to look at all the detail, but after a half hour I still can’t find very much that isn’t cover-up for a gift shop. I’ll take the next train that comes in, going clockwise around the park for the rest of the review. Just as Main Street is the prologue, Tomorrowland is definitely supposed to be the final act before the curtain call, right?

Walt Disney World Railroad

Whenever I encounter a theme park attraction that takes the form of public transportation, the most crucial factor for me is that it needs to function efficiently as such. I loved trains as a kid, but I still knew that if it wasn’t taking the scenic route (while aboard the Walt Disney World Railroad you spend a lot of time looking at subtropical shrubs, maintenance roads, and a few weathered dioramas while a narrator describes the much more exciting attractions remotely passing by) it had to get us from Point A to Point B faster than we could have managed by walking. Where the Main Street Vehicles fail in this regard, the Walt Disney World Railroad is a moderately useful piece of infrastructure if approached with a proper strategy. If the locomotive has arrived just as you’re getting off Splash Mountain and Storybook Circus was already your next intended destination, then the railroad will momentarily seem like the best ride you’ve ever taken at the Magic Kingdom. If you want to go

me is that it needs to function efficiently as such. I loved trains as a kid, but I still knew that if it wasn’t taking the scenic route (while aboard the Walt Disney World Railroad you spend a lot of time looking at subtropical shrubs, maintenance roads, and a few weathered dioramas while a narrator describes the much more exciting attractions remotely passing by) it had to get us from Point A to Point B faster than we could have managed by walking. Where the Main Street Vehicles fail in this regard, the Walt Disney World Railroad is a moderately useful piece of infrastructure if approached with a proper strategy. If the locomotive has arrived just as you’re getting off Splash Mountain and Storybook Circus was already your next intended destination, then the railroad will momentarily seem like the best ride you’ve ever taken at the Magic Kingdom. If you want to go from Main Street to Space Mountain and the train has just left the station, then you’re better off hiking it. Some might insist that the railroad’s “Disney magic” can’t be quantified using such utilitarian standards, but considering the average visitor will only ride nine attractions in a day I suspect more people use the train in the second scenario rather than the first. And that’s a shame.

from Main Street to Space Mountain and the train has just left the station, then you’re better off hiking it. Some might insist that the railroad’s “Disney magic” can’t be quantified using such utilitarian standards, but considering the average visitor will only ride nine attractions in a day I suspect more people use the train in the second scenario rather than the first. And that’s a shame.

Grade: C-

Adventureland

In a post-Animal Kingdom Walt Disney World, it might be reasonable to wonder if Adventureland still has the same relevancy for audiences. Of course the two are very different; Adventureland is a bit like reading a comic book, while Animal Kingdom tries to be like a National Geographic documentary. Still, I can’t help but shake the feeling (especially in the inevitable comparison between the Jungle Cruise and the Kilimanjaro Safaris) that Adventureland was designed for a different generation than those who visit today. Mixing African, Polynesian, Caribbean, and even Arabian influences under one generic label could easily be regarded as a mistake by today’s more culturally sensitive audiences… and probably more by kids than adults. As a 1990’s kid when environmentalism and conservation became really mainstream, you had to know things like the difference African and Indian elephants to do your kid duties correctly, and any anachronisms or anatopisms

for audiences. Of course the two are very different; Adventureland is a bit like reading a comic book, while Animal Kingdom tries to be like a National Geographic documentary. Still, I can’t help but shake the feeling (especially in the inevitable comparison between the Jungle Cruise and the Kilimanjaro Safaris) that Adventureland was designed for a different generation than those who visit today. Mixing African, Polynesian, Caribbean, and even Arabian influences under one generic label could easily be regarded as a mistake by today’s more culturally sensitive audiences… and probably more by kids than adults. As a 1990’s kid when environmentalism and conservation became really mainstream, you had to know things like the difference African and Indian elephants to do your kid duties correctly, and any anachronisms or anatopisms were to be immediately called on with that smarty-pants attitude kids have. (Okay, maybe not all kids were this way, but still…) Today Adventureland is probably the most self-consciously comedic of the Magic Kingdom’s lands, to distinguish itself from the “authenticity” of the Animal Kingdom, and the theme is more a pastiche of American popular cultural (especially between the 1930’s to 1970’s) than it is about the “real” foreign cultures it caricatures.

were to be immediately called on with that smarty-pants attitude kids have. (Okay, maybe not all kids were this way, but still…) Today Adventureland is probably the most self-consciously comedic of the Magic Kingdom’s lands, to distinguish itself from the “authenticity” of the Animal Kingdom, and the theme is more a pastiche of American popular cultural (especially between the 1930’s to 1970’s) than it is about the “real” foreign cultures it caricatures.

Jungle Cruise

On the surface the Jungle Cruise is a guided tour of a hyperreal tropical river basin with numerous robotic animals and exotic sets to look at, but there are a couple layers of subtext to peel back to understand what the Jungle Cruise is really about. First it’s kind of a corny, outdated attraction, so the skippers tell a continuous line of jokes either to poke fun at or distract us from the obvious fakeness of the sets and stiff movements of the creatures. The skippers know it’s all a hoax, the passengers know it’s all a hoax, and both sides know that the other side knows they know, but this knowledge can only be indirectly acknowledged through the metaphorical wink-winks that are exchanged after every punch line. However, since the jokes are also kind of corny and obviously recycled, there becomes a second layer of subtext on top of this. The skippers know the jokes they’re telling are lame (revealed by their droll delivery of obviously scripted material); the audience knows the jokes are lame (watch folk’s faces for the slight “so-bad-it’s-good” cringe

to peel back to understand what the Jungle Cruise is really about. First it’s kind of a corny, outdated attraction, so the skippers tell a continuous line of jokes either to poke fun at or distract us from the obvious fakeness of the sets and stiff movements of the creatures. The skippers know it’s all a hoax, the passengers know it’s all a hoax, and both sides know that the other side knows they know, but this knowledge can only be indirectly acknowledged through the metaphorical wink-winks that are exchanged after every punch line. However, since the jokes are also kind of corny and obviously recycled, there becomes a second layer of subtext on top of this. The skippers know the jokes they’re telling are lame (revealed by their droll delivery of obviously scripted material); the audience knows the jokes are lame (watch folk’s faces for the slight “so-bad-it’s-good” cringe while forcing a laugh at the skipper’s “you must be in da-Nile” punch line); and each side knows the other side knows they know… yet we continue to mutually play along and pretend it’s all a laugh riot. Maybe this format of employing multiple layers of metatextual irony to avoid actually making a better attraction could work if the skippers were given more freedom to experiment with their own material (surely plenty of skippers must be aspiring stand-up comics in need of a day job?), but after several laps the only variable I encountered was the guides’ level of perkiness brought to the same series of worn out puns, which varied Goldilocks style between gratingly chipper, tiredly sarcastic, and one that was “just right”.

while forcing a laugh at the skipper’s “you must be in da-Nile” punch line); and each side knows the other side knows they know… yet we continue to mutually play along and pretend it’s all a laugh riot. Maybe this format of employing multiple layers of metatextual irony to avoid actually making a better attraction could work if the skippers were given more freedom to experiment with their own material (surely plenty of skippers must be aspiring stand-up comics in need of a day job?), but after several laps the only variable I encountered was the guides’ level of perkiness brought to the same series of worn out puns, which varied Goldilocks style between gratingly chipper, tiredly sarcastic, and one that was “just right”.

Grade: C-

Walt Disney’s Enchanted Tiki Room

Walt Disney’s Enchanted Tiki Room

This was on my list of must-do’s for its long history dating back to the Golden Age of Disney in 1963 at the California park and copied for the Magic Kingdom’s debut in 1971. This audio-animatronic musical show feels distinctly a product of the 1960’s, and not in an entirely good way. The show’s “cast” consists of 150 robotic birds suspended from the ceiling that sing songs with several tiki heads and jumping fountains, and most of these figures are limited to binary position flapping mouths and one or two other simple movements. Thus when the entire chorus joins in on “The Tiki Tiki Tiki Room”, part of the music’s instrumentation is supplied from the sounds of hundreds of air pistons and clacking plastic parts triggering in (near) unison. Focusing on so many small moving parts from a distance can get tiresome after more than one song, so it’s probably better to just relax and listen to the music and comedy sketch interludes, both of which are also somewhat dated. Cultural stereotypes are a dominant form of the Tiki Room’s humor (the center four “host” parrots are indistinguishable apart from their strong Mexican, Irish, French, or German accents), while the music is firmly in the Disney tradition of feel-good sing-a-long-songs with a Polynesian inflection. It’s too bad the show’s best joke doesn’t happen until we’re already on our way out, when the birds sing an alternative version of “Heigh-Ho” that urges us out the door we go.

plastic parts triggering in (near) unison. Focusing on so many small moving parts from a distance can get tiresome after more than one song, so it’s probably better to just relax and listen to the music and comedy sketch interludes, both of which are also somewhat dated. Cultural stereotypes are a dominant form of the Tiki Room’s humor (the center four “host” parrots are indistinguishable apart from their strong Mexican, Irish, French, or German accents), while the music is firmly in the Disney tradition of feel-good sing-a-long-songs with a Polynesian inflection. It’s too bad the show’s best joke doesn’t happen until we’re already on our way out, when the birds sing an alternative version of “Heigh-Ho” that urges us out the door we go.

Grade: D

Vastly inferior to the much longer California version, and the updated Jack Sparrow/Blackbeard overlay hasn’t helped matters in Florida either. Even in California I find Pirates to be a ride (institution, really) that starts strong but fizzles into tedium by the end, and shortening the layout in Florida has only compressed the timeline rather than trim out the fluff. The first several scenes form one of the best dark ride sequences ever built, establishing the attraction as not simply another pirate yarn but something that could speak deeply to the nature of one’s childhood stories and dreams, as well as the hopes and fears they inspire. The pirate’s voyage begins in the dark of night across moonlit water and in the deep recesses of a cave… all Jungian archetypal symbols that represent the unconscious. The nightmarish quality to this opener makes it so that when we finally dock in Puerto Dorado it feels less like a scene change in a literal narrative than the arrival in our own metaphysical dreamscape. Sadly this sensation is fleeting, as the narrative devolves into a standard-issue (and, honestly, kind of dull) treasure hunt story told with stiff robotic figures that can only convey emotion through raised eyebrows, cocked heads, or other exaggerated motions that a programmer can substitute in the absence of living facial expressions. Despite the obvious potential for this story to be a morality play about the greed and recklessness of a pirate’s life,2 it instead ends with Jack Sparrow sitting atop a pile of gold and loot victoriously, a decidedly materialist “happy ending”

the deep recesses of a cave… all Jungian archetypal symbols that represent the unconscious. The nightmarish quality to this opener makes it so that when we finally dock in Puerto Dorado it feels less like a scene change in a literal narrative than the arrival in our own metaphysical dreamscape. Sadly this sensation is fleeting, as the narrative devolves into a standard-issue (and, honestly, kind of dull) treasure hunt story told with stiff robotic figures that can only convey emotion through raised eyebrows, cocked heads, or other exaggerated motions that a programmer can substitute in the absence of living facial expressions. Despite the obvious potential for this story to be a morality play about the greed and recklessness of a pirate’s life,2 it instead ends with Jack Sparrow sitting atop a pile of gold and loot victoriously, a decidedly materialist “happy ending” that contradicts the abstract journey through the collective unconscious required to get there. The happy ending becomes all the happier when we’re spat out into a gift shop a few moments later so that we may collect our own pirate’s loot, although the only take-home for me was a nagging feeling that I had witnessed a potentially good attraction that had been compromised by outside interests uncommitted to making a truly great attraction.

that contradicts the abstract journey through the collective unconscious required to get there. The happy ending becomes all the happier when we’re spat out into a gift shop a few moments later so that we may collect our own pirate’s loot, although the only take-home for me was a nagging feeling that I had witnessed a potentially good attraction that had been compromised by outside interests uncommitted to making a truly great attraction.

Grade: C

Frontierland

Of the original lands that opened in Anaheim in 1955, I think Frontierland benefited the most from the move eastward when Walt Disney World opened in 1971. The Magic Kingdom is a much more spacious park than Disneyland, and while some areas lose their energy or intimacy within the additional negative space, the extra breathing room vastly improves a naturally themed environment like Frontierland’s American west. Helping matters is the fact that real ghost towns and sun-baked desert landscapes are a considerable rarity in Florida compared to California, thus giving more purpose to paying to see a theme park’s interpretation of the material. Also the attraction selection is an marked improvement: In addition to Big Thunder Mountain, Magic Kingdom’s Frontierland has Splash Mountain, the Country Bear Jamboree, and Tom Sawyer Island, whereas Disneyland’s Frontierland has the Rivers of America, a kid’s playground, and pirates (?). During a day at each park

I think Frontierland benefited the most from the move eastward when Walt Disney World opened in 1971. The Magic Kingdom is a much more spacious park than Disneyland, and while some areas lose their energy or intimacy within the additional negative space, the extra breathing room vastly improves a naturally themed environment like Frontierland’s American west. Helping matters is the fact that real ghost towns and sun-baked desert landscapes are a considerable rarity in Florida compared to California, thus giving more purpose to paying to see a theme park’s interpretation of the material. Also the attraction selection is an marked improvement: In addition to Big Thunder Mountain, Magic Kingdom’s Frontierland has Splash Mountain, the Country Bear Jamboree, and Tom Sawyer Island, whereas Disneyland’s Frontierland has the Rivers of America, a kid’s playground, and pirates (?). During a day at each park I “stop by” Disneyland’s Frontierland, and “go to” the Magic Kingdom’s.

I “stop by” Disneyland’s Frontierland, and “go to” the Magic Kingdom’s.

The Country Bear Jamboree

This is yet another Disney-produced musical show that can be performed by pushing a start button. While I’m not typically a fan of the genre, I was most keen to try it out after being told by David Younger (of Theme Park Theory) that Marc Davis’ work on the Country Bear Jamboree perhaps best represents an example of auteur theory as applied to a theme park attraction. Although I’m uncertain how much I can attribute the presence of an auteur to this show’s successfulness, it does have a unique brand of off-beat humor that I honestly found fairly charming. The show and its creators seem deeply endeared to the tradition of American folk and country music, even as they simultaneously finds ways to mock its eclectic cast of performers. (My favorite bit: the deadpan performance of “Blood on the Saddle” by the oblivious Big Al character with his out-of-tune guitar.) It also helps that the bears’ cartoon expressiveness is brought to life by some of the most detailed and elaborate audio-animatronics in the Magic Kingdom, and there are nearly twenty different performers brought on and off stage ensuring that the show never becomes repetitive. Apparently the Jamboree has been shortened by about six minutes after a recent refurbishment; I’d be curious to see the material I missed.

of off-beat humor that I honestly found fairly charming. The show and its creators seem deeply endeared to the tradition of American folk and country music, even as they simultaneously finds ways to mock its eclectic cast of performers. (My favorite bit: the deadpan performance of “Blood on the Saddle” by the oblivious Big Al character with his out-of-tune guitar.) It also helps that the bears’ cartoon expressiveness is brought to life by some of the most detailed and elaborate audio-animatronics in the Magic Kingdom, and there are nearly twenty different performers brought on and off stage ensuring that the show never becomes repetitive. Apparently the Jamboree has been shortened by about six minutes after a recent refurbishment; I’d be curious to see the material I missed.

Big Thunder Mountain Railroad

The physics that govern roller coaster designs are the opposite of what their dramatic structure should be. A good show needs to have a big finish, but roller coasters by their nature usually start with their biggest tricks and then become tamer near the end as energy is lost to friction. Despite WED Enterprises’ intense focus on story and the advantage of having three lift hills to moderate the energy throughout the ride, Big Thunder Mountain Railroad still falls victim to this common mistake of coaster design. The first cavernous lift hill that’s threaded through a split waterfall: spectacular. The first gravity-driven section with several drops and tight curves including a trick-track past a ghost town: pretty fun. The second gravity-driven section with the one hill that almost produces airtime and a couple close headchopper effects: getting a bit repetitive, but still fun. The third lift, with the ominous tremors and off-kilter rails: good, now the tension is mounting. And then the final gravity driven section: wait, that’s it? It’s over? It’s not a particularly thrilling coaster before that point yet I’m willing to enjoy it for what it is, but in the last act the themed storyline is horribly at odds with the actual coaster experience. The setting around the third lift seems intended to build tension, while the final gravity-driven section on the other side (by far the slowest and gentlest part of the layout) functions as the coaster’s denouement. Missing from this arc is any sort

The first gravity-driven section with several drops and tight curves including a trick-track past a ghost town: pretty fun. The second gravity-driven section with the one hill that almost produces airtime and a couple close headchopper effects: getting a bit repetitive, but still fun. The third lift, with the ominous tremors and off-kilter rails: good, now the tension is mounting. And then the final gravity driven section: wait, that’s it? It’s over? It’s not a particularly thrilling coaster before that point yet I’m willing to enjoy it for what it is, but in the last act the themed storyline is horribly at odds with the actual coaster experience. The setting around the third lift seems intended to build tension, while the final gravity-driven section on the other side (by far the slowest and gentlest part of the layout) functions as the coaster’s denouement. Missing from this arc is any sort of emotional climax, which is a gaping big hole to have from a story structure perspective. Even many of the Arrow Dynamics mine trains built for regional amusement parks up to a decade prior to BTM’s debut usually had a better sense of dramatic layout construction, and using a tighter budget than Disney. California’s version is the same way, although it seems Imagineers did realize the problem and took steps to correct it on subsequent international entries in the Big Thunder canon by including a bat cave (Tokyo), an underwater drop (Paris), and finally a “dynamite” LIM launch (Hong Kong, as Big Grizzly Mountain). Of course there’s the theming on Big Thunder: there’s more of it, but it’s just more that whizzes by, and apart from the first lift it does little to transcend the original mine train coasters at Six Flags besides distracting us with more visual clutter.

of emotional climax, which is a gaping big hole to have from a story structure perspective. Even many of the Arrow Dynamics mine trains built for regional amusement parks up to a decade prior to BTM’s debut usually had a better sense of dramatic layout construction, and using a tighter budget than Disney. California’s version is the same way, although it seems Imagineers did realize the problem and took steps to correct it on subsequent international entries in the Big Thunder canon by including a bat cave (Tokyo), an underwater drop (Paris), and finally a “dynamite” LIM launch (Hong Kong, as Big Grizzly Mountain). Of course there’s the theming on Big Thunder: there’s more of it, but it’s just more that whizzes by, and apart from the first lift it does little to transcend the original mine train coasters at Six Flags besides distracting us with more visual clutter.

Grade: C

Splash Mountain

If there’s something in the nature of roller coasters that works against the rules of theatricality, then inversely there also seems to be something in the nature of log flumes and water attractions that fits naturally to dramatic structuring. Since log flumes can’t easily sustain high speeds and navigate complex maneuvers, they instead rely on only a couple of big drops that can be used to signify key dramatic points in the narrative where an “emotional shock” is needed, particularly if placed towards the end to function as a grand climax (adjusting the drop height is an easy way to quantify the emotional impact of a plot point), and the rest of the slow-moving trough sections can be used to develop and flesh out other elements of the themed storyline without rushing by them. Although Knott’s Timber Mountain Log Ride established the basic principles of the log flume in a theme park setting, it was Splash Mountain that cemented the rules of the genre by carefully integrated the flume dynamics to fit Freytag’s pyramid of dramatic structure: Introduction (“How Do You Do?”, with the outdoor establishment of the rural Georgia setting, Slippin’ Falls, and indoor establishment of the principal characters); Rising Action (“Ev’rybody Has a Laughing Place”, the double indoor drops and dark cave sequences); Climax (the iconic drop into the briar patch); and Resolution

as a grand climax (adjusting the drop height is an easy way to quantify the emotional impact of a plot point), and the rest of the slow-moving trough sections can be used to develop and flesh out other elements of the themed storyline without rushing by them. Although Knott’s Timber Mountain Log Ride established the basic principles of the log flume in a theme park setting, it was Splash Mountain that cemented the rules of the genre by carefully integrated the flume dynamics to fit Freytag’s pyramid of dramatic structure: Introduction (“How Do You Do?”, with the outdoor establishment of the rural Georgia setting, Slippin’ Falls, and indoor establishment of the principal characters); Rising Action (“Ev’rybody Has a Laughing Place”, the double indoor drops and dark cave sequences); Climax (the iconic drop into the briar patch); and Resolution (“Zip-A-Dee-Doo-Dah”, the return trough channel to the station). At over ten minutes in length it has plenty of time to immerse riders each of these story chapters so the emotional transformation from beginning to end can be noticeably felt, even if it suffers from a few issues such as an overly long delay between the drop climax and the final show scenes, or some animatronics and set pieces that seem in dire need of a refurbishment. Nevertheless Splash Mountain is a prime example of how to merge traditional amusement park thrills with immersive story-based entertainment, and has helped cement the log flume attraction as a neoclassical Disney favorite.

(“Zip-A-Dee-Doo-Dah”, the return trough channel to the station). At over ten minutes in length it has plenty of time to immerse riders each of these story chapters so the emotional transformation from beginning to end can be noticeably felt, even if it suffers from a few issues such as an overly long delay between the drop climax and the final show scenes, or some animatronics and set pieces that seem in dire need of a refurbishment. Nevertheless Splash Mountain is a prime example of how to merge traditional amusement park thrills with immersive story-based entertainment, and has helped cement the log flume attraction as a neoclassical Disney favorite.

Grade: B

As the welcum sign says, if’n you like dark caves, mystery mines, bottomless pits, shakey bridges n big rocks, you’re probably bound to enjoy spending some time on Frontierland’s Tom Sawyer Island. The river rafts required to reach the island act as a natural choke point for the entrance so it should usually be one of the least crowded areas in the Magic Kingdom, and the unpolished rustic appeal of trails through the trees with various gags to explore at your own pace in whatever order you’d like makes it a refreshingly different kind of activity for the Magic Kingdom. The paths are even made with real dirt and woodchips, now that’s what I call “attention to detail”! Of course it could be easy to argue that this is no substitute for hiking in an actual National Park, but since it’s at Disney I think it’s perfectly fine to have someplace where you can momentarily escape when you start to feel overwhelmed by how much “Disney” there is everywhere else. A word of warning, the floating barrel bridge should not be attempted to cross by anyone who’s recently thrown back a few bottles.

this is no substitute for hiking in an actual National Park, but since it’s at Disney I think it’s perfectly fine to have someplace where you can momentarily escape when you start to feel overwhelmed by how much “Disney” there is everywhere else. A word of warning, the floating barrel bridge should not be attempted to cross by anyone who’s recently thrown back a few bottles.

Grade: C+

Liberty Square

If the overall tone of Adventureland is “silly” and the tone of Frontierland “romantic”, then Liberty Square must represent the Magic Kingdom’s morbid side. By my count there are at least 1038 dead people in Liberty Square: the 999 ghosts haunting the mansion, plus 39 dead presidents in the Hall of Presidents. How else to make the thematic connection between this small area’s most important attractions than that they all feature old American buildings filled with magically reanimated corpses? The Revolutionary American architecture is a nice diversion from the cartoonish fantasy in the rest of the park, and is completely unique to the Magic Kingdom, although there are already a lot of tourist attractions that do this sort of thing on a larger scale, and with more educational value, too. Not that it matters much as Liberty Square is also home to one of my favorite attractions in central Florida.

represent the Magic Kingdom’s morbid side. By my count there are at least 1038 dead people in Liberty Square: the 999 ghosts haunting the mansion, plus 39 dead presidents in the Hall of Presidents. How else to make the thematic connection between this small area’s most important attractions than that they all feature old American buildings filled with magically reanimated corpses? The Revolutionary American architecture is a nice diversion from the cartoonish fantasy in the rest of the park, and is completely unique to the Magic Kingdom, although there are already a lot of tourist attractions that do this sort of thing on a larger scale, and with more educational value, too. Not that it matters much as Liberty Square is also home to one of my favorite attractions in central Florida.

I suspect many patrons enter the Hall of Presidents out of a sense of civic duty rather than from any innate desire to sit through an austere 20 minute multi-media presentation on American history when they could have ridden the Haunted Mansion within the same timeframe. I don’t “want to” see the Hall of Presidents, I “should” see the Hall of Presidents. Of course we could also be there from an innate desire to gawk at the spectacle of technology that seemingly lets dead presidents return from the grave, even though Disney tries to underplay the significance of our collective tech fetishism to the show’s patriotic importance (perhaps similar to the way Nascar might try to gloss over the universal appeal of watching their race cars crash and burn). However, be forewarned that the majority of the show’s running time is devoted to a Ken Burns style documentary (narrated by Morgan Freeman) that briefly summarizes the presidencies of Washington, Jackson, Lincoln, Roosevelt, the other Roosevelt, and Kennedy. When they finally do bring the presidents onstage there’s little more than a spotlight roll call with Freeman reading down the list while each man only gives a subtle nod, seemingly underutilizing the hi-tech figures especially since we can’t observe them up close in detail. Obama (and an earlier bit by Lincoln) are the only two AAs that are ever given talking time, and the format oddly seems to encourage the interpretation that 200+ years of presidential history were all quietly anticipating the eventual Obama administration,

their race cars crash and burn). However, be forewarned that the majority of the show’s running time is devoted to a Ken Burns style documentary (narrated by Morgan Freeman) that briefly summarizes the presidencies of Washington, Jackson, Lincoln, Roosevelt, the other Roosevelt, and Kennedy. When they finally do bring the presidents onstage there’s little more than a spotlight roll call with Freeman reading down the list while each man only gives a subtle nod, seemingly underutilizing the hi-tech figures especially since we can’t observe them up close in detail. Obama (and an earlier bit by Lincoln) are the only two AAs that are ever given talking time, and the format oddly seems to encourage the interpretation that 200+ years of presidential history were all quietly anticipating the eventual Obama administration, although most likely this is an accidental by-product of Disney’s showmanship tendencies that require a big grand finale. Credit goes to at least attempting to make the show as non-partisan as possible, and Walt Disney’s message that every president has been equally important to the success of the American democratic experiment is a noble one, even if most informed people in the audience are likely to subtitle the show in their own minds as “The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly”.

although most likely this is an accidental by-product of Disney’s showmanship tendencies that require a big grand finale. Credit goes to at least attempting to make the show as non-partisan as possible, and Walt Disney’s message that every president has been equally important to the success of the American democratic experiment is a noble one, even if most informed people in the audience are likely to subtitle the show in their own minds as “The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly”.

Grade: C

The Haunted Mansion

Before anything else we first must face the question of suicide. It is only after we fully confront this unanswerable problem that we can start the party that is life. More than forty years since its debut, the Haunted Mansion (along with its western and eastern counterparts) remains the most radical attraction ever built at a Disney theme park due to its complete reversal of the traditional ghost story arc. Here it begins with the macabre death of the main character (the suicidal remains of the mansion’s “ghost host” narrator dangling above our heads) and then rewinds the horror backward until we’re dancing along with the undead in a jazzy graveyard jam. Where a lesser attraction might have tried to use the “hitchhiking ghost” illusion in a serious context, in the Haunted Mansion we’re obviously meant to laugh at the final reflected image of ourselves

Before anything else we first must face the question of suicide. It is only after we fully confront this unanswerable problem that we can start the party that is life. More than forty years since its debut, the Haunted Mansion (along with its western and eastern counterparts) remains the most radical attraction ever built at a Disney theme park due to its complete reversal of the traditional ghost story arc. Here it begins with the macabre death of the main character (the suicidal remains of the mansion’s “ghost host” narrator dangling above our heads) and then rewinds the horror backward until we’re dancing along with the undead in a jazzy graveyard jam. Where a lesser attraction might have tried to use the “hitchhiking ghost” illusion in a serious context, in the Haunted Mansion we’re obviously meant to laugh at the final reflected image of ourselves as we seemingly become undead spirits, a final gag that becomes the punchline to one long joke about mortality. This isn’t to say that every element of the Mansion fits perfectly to the story – there’s an attic scene between the ballroom and graveyard filled with trick portrait photographs that disrupts the continuity of the mansion’s transformation into a lively and festive atmosphere (Roland Barthes wrote that death is implicit in every photograph due to the way they consciously remind us of the person or world “that-has-been”, so such a scene would have been more appropriate towards the beginning of the storyline), and I still think the rooms are filled with a little too much technological showmanship for the mansion to ever feel truly haunted (compared to the creaky low-tech

as we seemingly become undead spirits, a final gag that becomes the punchline to one long joke about mortality. This isn’t to say that every element of the Mansion fits perfectly to the story – there’s an attic scene between the ballroom and graveyard filled with trick portrait photographs that disrupts the continuity of the mansion’s transformation into a lively and festive atmosphere (Roland Barthes wrote that death is implicit in every photograph due to the way they consciously remind us of the person or world “that-has-been”, so such a scene would have been more appropriate towards the beginning of the storyline), and I still think the rooms are filled with a little too much technological showmanship for the mansion to ever feel truly haunted (compared to the creaky low-tech spooks that inhabit, say, Knoebel’s Haunted Mansion, where the ride’s history and thus the presence of death become omnipresent). Still, these are relatively minor shortcomings for an attraction that daringly manages to transform our initial existential dread into something that eventually becomes quietly life-affirming. In the end the Haunted Mansion offers no answer for how to best “find a way out”, but it doesn’t matter so long as it helps us live to laugh another day.

spooks that inhabit, say, Knoebel’s Haunted Mansion, where the ride’s history and thus the presence of death become omnipresent). Still, these are relatively minor shortcomings for an attraction that daringly manages to transform our initial existential dread into something that eventually becomes quietly life-affirming. In the end the Haunted Mansion offers no answer for how to best “find a way out”, but it doesn’t matter so long as it helps us live to laugh another day.

Grade: A-

_______Fantasyland_______

It seems ironic that “fantasy” has become such a narrow genre label within contemporary usage. Nowadays if you label something “fantasy” that always, always, always implies a setting in (or loosely resembling) Medieval Europe (maybe Classical or Renaissance Europe if it’s particularly imaginative fantasy), and you can be sure that you can’t throw a stone without hitting an elf, dwarf, wizard, or dragon… yet flying spaghetti monsters remain completely invisible. Since when did we become so dependent on the brothers Grimm and J.R.R. Tolkien to feed our imaginations? I applaud attractions like “it’s a small world” if only because they try to escape the confines of old Europe in creating a unique aesthetic setting that can still be called “fantasy”. Then again, I absolutely do not want to see Figment from Epcot’s Imagination pavilion anywhere near the Magic Kingdom, so perhaps I should be careful in what I ask for.

to see Figment from Epcot’s Imagination pavilion anywhere near the Magic Kingdom, so perhaps I should be careful in what I ask for.

“it’s a small world”

“it’s a small world” is the one attraction at Disney parks that has given me more grief in my role as a critic than any other attraction. On the one hand, it has a completely original artistic style that rejects hyperreal simulacra while conveying a simple, non-pandering message for world peace that resonates across generational divides, and in the process has made one of the deepest footprints on the pop-cultural landscape of any theme park attraction ever built. But on the other hand… it’s a small world. A small world where the music is stuck in an endless reprise and the thousands of dolls will never cease dancing like they’re at a house party thrown by Sisyphus. A small world where no matter what country I’m in it all looks like a jellybean factory recently blew up nearby, and the kaleidoscopic shapes and colors will burn imprints into my retinas after ten minutes of exposure. And a small world where no matter how slow my boat seems to be floating down the channel it will still inevitably get backed up for several minutes behind other boats just before reaching the unload platform. Perhaps the solution to my grief is to not approach “it’s a small world” as a critic, but simply as myself. In that case,

A small world where the music is stuck in an endless reprise and the thousands of dolls will never cease dancing like they’re at a house party thrown by Sisyphus. A small world where no matter what country I’m in it all looks like a jellybean factory recently blew up nearby, and the kaleidoscopic shapes and colors will burn imprints into my retinas after ten minutes of exposure. And a small world where no matter how slow my boat seems to be floating down the channel it will still inevitably get backed up for several minutes behind other boats just before reaching the unload platform. Perhaps the solution to my grief is to not approach “it’s a small world” as a critic, but simply as myself. In that case, speaking for myself, on the outside I probably appear with glazed eyes and mouth slightly agape, but inside I’m still smiling a bit at the excessively simple and simply excessive pageantry of the whole ride. I guess that means that I must enjoy it on some level, even if I’m never going to be its target audience. However, also speaking for myself, I find that the world usually seems the most wondrous when I’m aware of its vastness, not its smallness.

speaking for myself, on the outside I probably appear with glazed eyes and mouth slightly agape, but inside I’m still smiling a bit at the excessively simple and simply excessive pageantry of the whole ride. I guess that means that I must enjoy it on some level, even if I’m never going to be its target audience. However, also speaking for myself, I find that the world usually seems the most wondrous when I’m aware of its vastness, not its smallness.

Grade: C+

Peter Pan’s Flight

At most other parks the longest lines usually come before the newest and biggest rides. But the Magic Kingdom isn’t like most other parks, and here the longest line usually comes before Peter Pan’s Flight, which is neither the park’s newest, nor biggest. This is one of the original “drive-thru movie” style dark rides, and I’ve honestly never had much love for the genre so its “classic” status means little to me. As a form of storytelling, it’s only a little more effective than a movie trailer. While trailers and dark rides are each a unique medium with their own special rulebooks for the delivery of a neatly crafted emotional arc over a brief span of a couple minutes, both are ultimately subservient to the originating feature length film, unable to stand on their own artistic merits without it. Peter Pan’s Flight is a small but detailed ride with only a couple memorable effects, cast in the shadow of a giant name that seems

before the newest and biggest rides. But the Magic Kingdom isn’t like most other parks, and here the longest line usually comes before Peter Pan’s Flight, which is neither the park’s newest, nor biggest. This is one of the original “drive-thru movie” style dark rides, and I’ve honestly never had much love for the genre so its “classic” status means little to me. As a form of storytelling, it’s only a little more effective than a movie trailer. While trailers and dark rides are each a unique medium with their own special rulebooks for the delivery of a neatly crafted emotional arc over a brief span of a couple minutes, both are ultimately subservient to the originating feature length film, unable to stand on their own artistic merits without it. Peter Pan’s Flight is a small but detailed ride with only a couple memorable effects, cast in the shadow of a giant name that seems to be the real reason for drawing in the longest lines in the park. Or the long lines are because it’s indoors, there’s no minimum height limit, and single-bench vehicles provide less than ideal throughput. Either way, FastPass is highly recommended.

to be the real reason for drawing in the longest lines in the park. Or the long lines are because it’s indoors, there’s no minimum height limit, and single-bench vehicles provide less than ideal throughput. Either way, FastPass is highly recommended.

Grade: C-

Mickey’s PhilharMagic

Here’s a litmus test for the quality of any theme park 4D cinema: would you want to watch the same short film if it were offered as a DVD extra for your home television? It’s all too easy for such attractions to gloss over a weak story with an abundance of 4D special effects, in which the hero’s conquest over the evil villain becomes a barely memorable plot hiccup in comparison to that time the comic relief guy spit his drink on the audience. Mickey’s PhilharMagic would probably fail such a test, although part of that might be because I’ve already seen roughly 80% of the material on DVD (well, VHS). Most of the short film consists of a musical medley from their most popular animated films, tied together by a plot involving Donald Duck becoming a mistaken sorcerer’s apprentice to a magical orchestra. (Despite the title, Mickey remains off-screen for the vast majority of the show’s runtime.) It recalls enough Saturday morning cartoons that I can find it relatively entertaining, although I’d be lying if I didn’t admit its biggest appeal is the chance to sit in the dark air conditioning for a few minutes.

of 4D special effects, in which the hero’s conquest over the evil villain becomes a barely memorable plot hiccup in comparison to that time the comic relief guy spit his drink on the audience. Mickey’s PhilharMagic would probably fail such a test, although part of that might be because I’ve already seen roughly 80% of the material on DVD (well, VHS). Most of the short film consists of a musical medley from their most popular animated films, tied together by a plot involving Donald Duck becoming a mistaken sorcerer’s apprentice to a magical orchestra. (Despite the title, Mickey remains off-screen for the vast majority of the show’s runtime.) It recalls enough Saturday morning cartoons that I can find it relatively entertaining, although I’d be lying if I didn’t admit its biggest appeal is the chance to sit in the dark air conditioning for a few minutes. The other parks at the Disney World resort have much better 4D cinema attractions.

The other parks at the Disney World resort have much better 4D cinema attractions.

Grade: D+

The Many Adventures of Winnie the Pooh

This is a competently-made dark ride that uses a variety of artistically inspired set pieces and special effects to tell a compelling story in the 100 Acre Woods about the perils of hard drug abuse. In it, Pooh ignores his neighbor’s pleas for help during a hurricane that threatens to destroy his community so that he can find his next fix from his recently depleted honey stash. When none is to be found, his charlatan friend Tigger convinces him to steal honey from his neighbors. After surviving an out-of-body hallucination caused by honey withdrawal, Pooh wakes to find his community underwater and his best friend about to drown. He again ignores this when he discovers a stash of honey in a tree large enough to put his whole body inside. The community eventually reconstructs, and Pooh finds that the best way to manage his honey addiction is to consume even more honey. It’s like the family friendly version of “Requiem for a Dream”, except Pooh doesn’t have to have his paw amputated at the end. (Um, spoiler alert.) And yet people still think Universal is the edgier of the major theme park operators in Florida…

him to steal honey from his neighbors. After surviving an out-of-body hallucination caused by honey withdrawal, Pooh wakes to find his community underwater and his best friend about to drown. He again ignores this when he discovers a stash of honey in a tree large enough to put his whole body inside. The community eventually reconstructs, and Pooh finds that the best way to manage his honey addiction is to consume even more honey. It’s like the family friendly version of “Requiem for a Dream”, except Pooh doesn’t have to have his paw amputated at the end. (Um, spoiler alert.) And yet people still think Universal is the edgier of the major theme park operators in Florida…

Grade: C+

Interactivity can improve almost any flat ride experience, a claim of universality which cannot be made by most other categories of amusement attractions. The more intense interactive flat rides can become a first-person physics experiment, while the gentler rides can become a social activity; both types possibly benefit from increased mental stimulation over the monotonous motions of non-interactive flat ride counterparts. With an inert disk at the center of the seating that requires riders to join together to set their tea cup in motion (the amount of muscle you put into it directly controls how fast the cup spins; no button pushing or cord yanking here), the Mad Tea Party is an enduring example of rider interaction done right, even decades before “interactivity” became an amusement industry buzzword.

rider interaction done right, even decades before “interactivity” became an amusement industry buzzword.

Grade: C-

Dumbo the Flying Elephant

Some theme park fans might like to think that Disney’s storytelling and placemaking abilities allow their parks to completely transcend the ordinary amusement park experience, yet this possibly ignores the fact that at least two of their most iconic and popular attractions are essentially glamorized carnival rides (Dumbo and the Mad Tea Party, maybe a few others). This isn’t to denigrate these rides at all, only to point out that even at Disney you can’t deny the simple pleasures of spinning around in circles that make fairgrounds so popular. Of course the Magic Kingdom does it with a lot more class, and I even get an odd satisfaction just from thinking about all the extra capacity the new dueling arrangement offers. I can only assume this comes from spending too much time in slow-moving queues at other parks where I must entertain myself by mentally calculating the estimated throughput numbers. Still, regardless of how classy the presentation is within the Storybook Circus of New Fantasyland and how fast the line moves, I must ask now that I’ve done it once: am I ever going to voluntarily ride Dumbo again?

rides at all, only to point out that even at Disney you can’t deny the simple pleasures of spinning around in circles that make fairgrounds so popular. Of course the Magic Kingdom does it with a lot more class, and I even get an odd satisfaction just from thinking about all the extra capacity the new dueling arrangement offers. I can only assume this comes from spending too much time in slow-moving queues at other parks where I must entertain myself by mentally calculating the estimated throughput numbers. Still, regardless of how classy the presentation is within the Storybook Circus of New Fantasyland and how fast the line moves, I must ask now that I’ve done it once: am I ever going to voluntarily ride Dumbo again?

Grade: D+

It’s not Disney’s fault that the Vekoma Roller Skater would go on to become more popular than head lice since the Barnstormer’s 1996 debut, with a total of four now residing in central Florida alone. But even if Disney had signed an exclusivity contract with Vekoma (which would have been a bum deal for Vekoma, as they’ve managed to sell 75 other Roller Skaters worldwide, with a third of those being identical clones to the Barnstormer, sans chain lift and transfer track), it still would have been identifiable as a stock product. It’s one of the few Walt Disney World attractions that seems to exist first and foremost to fill a generic ride category (Magic Kingdom doesn’t have a children’s coaster, so let’s add one), with the details of where, how, and why it should fit in the rest of the themed environment being a secondary concern. (Even the much maligned Primeval Whirl had more thematic justification of the stock model spinning mouse choice in the context of the roadside Americana theme.) It’s not even defensible as a way to absorb capacity on a busy day since a maximum of 16 riders per dispatch still sucks by Disney standards. What sane individual waits an hour in line to experience twenty seconds of weaving helices? At least with the Great Goofini makeover and second train it’s leagues better than its single train, looney tunes styled Anaheim cousin, but that isn’t saying much.

add one), with the details of where, how, and why it should fit in the rest of the themed environment being a secondary concern. (Even the much maligned Primeval Whirl had more thematic justification of the stock model spinning mouse choice in the context of the roadside Americana theme.) It’s not even defensible as a way to absorb capacity on a busy day since a maximum of 16 riders per dispatch still sucks by Disney standards. What sane individual waits an hour in line to experience twenty seconds of weaving helices? At least with the Great Goofini makeover and second train it’s leagues better than its single train, looney tunes styled Anaheim cousin, but that isn’t saying much.

Grade: D

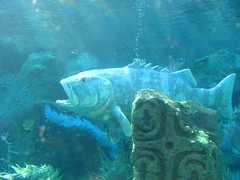

Under the Sea: Journey of the Little Mermaid

Under the Sea: Journey of the Little Mermaid

Well… it has a good queue line. Once we board the clamshell vehicles we’re then treated to a four minute thesis on the shortcomings of theme park attractions as a narrative art form. Much of it is technical in analysis: omnimovers demonstrate the completely the wrong choice of ride system for this particular story. Unlike the Haunted Mansion or Pirates of the Caribbean, which are very open-ended stories told via mood across space, the story of the Little Mermaid is mediated by events across time, and therefore requires a much more linear sequential ride format with clearly defined scene changes to advance the narrative. Both Peter Pan’s Flight and Adventures of Pooh are reasonably competent at this; the individual cars enter a room, a short scene plays out in front of them, and then you exit into the next room, where each door or dark threshold between scenes acts like the spatial equivalent of a cinematic cut. However, with a continuous chain of omnimovers it’s impossible to present any completed action directly to the audience for more than two seconds. Events and dialogue have to be open-ended and unfold in an infinite loop, so that you can enter and exit the scene at any moment and still have it work. But it doesn’t work with this story. Much of the action driving the plot on Under the Sea is still “closed”; meaning, as you enter Ursula’s chamber, you’re likely to hear the second half of a certain line of dialogue, followed by an empty pause (where in film we might expect a cut), and then only catch the first half of her next line (which must

at this; the individual cars enter a room, a short scene plays out in front of them, and then you exit into the next room, where each door or dark threshold between scenes acts like the spatial equivalent of a cinematic cut. However, with a continuous chain of omnimovers it’s impossible to present any completed action directly to the audience for more than two seconds. Events and dialogue have to be open-ended and unfold in an infinite loop, so that you can enter and exit the scene at any moment and still have it work. But it doesn’t work with this story. Much of the action driving the plot on Under the Sea is still “closed”; meaning, as you enter Ursula’s chamber, you’re likely to hear the second half of a certain line of dialogue, followed by an empty pause (where in film we might expect a cut), and then only catch the first half of her next line (which must convey the same basic idea as the first line we partially missed) before being scooted out into the next scene. This short-form narrative doesn’t even play like a trailer for the feature film; it’s more like randomly skipping ahead on the playback bar of the movie. So incoherent is the plot in Under the Sea that I had to read a synopsis afterward to figure out that Ursula is not the one responsible for the celebratory ending where Ariel and Prince Eric are united. Thus the thesis ends with a basic question of aesthetics: why retell this story at all if it wasn’t going to be retold well? The answer, however, is only too obvious; it simply has nothing to do with aesthetics.

convey the same basic idea as the first line we partially missed) before being scooted out into the next scene. This short-form narrative doesn’t even play like a trailer for the feature film; it’s more like randomly skipping ahead on the playback bar of the movie. So incoherent is the plot in Under the Sea that I had to read a synopsis afterward to figure out that Ursula is not the one responsible for the celebratory ending where Ariel and Prince Eric are united. Thus the thesis ends with a basic question of aesthetics: why retell this story at all if it wasn’t going to be retold well? The answer, however, is only too obvious; it simply has nothing to do with aesthetics.

Grade: D

Tomorrowland

Apparently the future already happened and we all missed it. Ignoring the quality of the attractions within it and just focusing on the environment, I think this might be one of my least favorite themed lands anywhere on Walt Disney World property. The main midway in particular is very visually cluttered, and despite the futurist theme it feels like the most outdated section of the park. This outdatedness would have been okay if it was the future as envisioned by a previous generation; perhaps from Walt’s perspective in the 1960’s as seen in the Carousel of Progress, or from Jules Verne’s fiction as seen at Disneyland Paris’ magnificent Discoveryland? However, here it’s not a coherent representation of anyone’s vision of the future, either past, present, or fictional. Cartoonish flourishes interrupt the sleek chrome aesthetic, advertisements for attractions (or even vacation properties) compete for precious attention resources, and after navigating through the dense black hole of tourists bottlenecked in the narrow arcade midway, the space then opens up in the back with Space Mountain and Carousel of Progress both seemingly located way out in the middle of the Florida swamplands. Movie-based attractions have become popular in recent years, yet proper science-fiction stories are almost completely extinct in Tomorrowland. Of the Pixar films they chose to include both Monsters, Inc. and Toy Story, but not WALL-E? A revamp is rumored once New Fantasyland is complete, and I say it can’t come soon enough.

representation of anyone’s vision of the future, either past, present, or fictional. Cartoonish flourishes interrupt the sleek chrome aesthetic, advertisements for attractions (or even vacation properties) compete for precious attention resources, and after navigating through the dense black hole of tourists bottlenecked in the narrow arcade midway, the space then opens up in the back with Space Mountain and Carousel of Progress both seemingly located way out in the middle of the Florida swamplands. Movie-based attractions have become popular in recent years, yet proper science-fiction stories are almost completely extinct in Tomorrowland. Of the Pixar films they chose to include both Monsters, Inc. and Toy Story, but not WALL-E? A revamp is rumored once New Fantasyland is complete, and I say it can’t come soon enough.

Monsters, Inc. Laugh Floor

This interactive comedy club using digital puppet technology based on characters from Monsters, Inc.3 will most likely require some patience from its audience members. Comedy is a subtle art that thrives on spontaneity and subversiveness, both increasingly hard resources to cultivate at the Magic Kingdom. The show is padded with a lot of pretty tepid puns and corny one-liners (the staged bits involving the curmudgeonly Roz seem particularly uninspired and stagnate the show’s pacing considerably). However, if you’re lucky your patience will be rewarded (hopefully more than once) during an interactive segment when an unexpected reply from the audience is met with a perfectly timed ad-lib from on stage (or, more accurately, from behind stage). Who knows, maybe you’ll also discover a gem from the audience-submitted jokes they read at the end, but the legal disclaimer during the preshow warning of the many rights given up by participating (including human) meant that the best texted-in joke they could collect from our group was the one asking how to make a hanky dance. Yeah, you can show us the exit now, thanks.

the audience is met with a perfectly timed ad-lib from on stage (or, more accurately, from behind stage). Who knows, maybe you’ll also discover a gem from the audience-submitted jokes they read at the end, but the legal disclaimer during the preshow warning of the many rights given up by participating (including human) meant that the best texted-in joke they could collect from our group was the one asking how to make a hanky dance. Yeah, you can show us the exit now, thanks.

Grade: D+

Stitch’s Great Escape

This is an excellent attraction for people who are either at a third grade maturity level or who might get enjoyment out of S&M activities. First you’re strapped down to your seat by a rigid horsecollar, then the lights are turned off, whereupon you’re subjected to five minutes of being sneezed on, jumped on, burped on, and sometimes spit on by a hyperactive blue creature called Stitch (voiced by a guy who has evidently swallowed an entire helium balloon). If that all sounds like too much fun, don’t worry because there are plenty of laborious talking exposition scenes added to the beginning and end of this experiential show to keep it from ever getting too exciting. However, to my eyes the best part of this attraction is that the authoritarian intergalactic penal system depicted in this story could potentially inspire a

This is an excellent attraction for people who are either at a third grade maturity level or who might get enjoyment out of S&M activities. First you’re strapped down to your seat by a rigid horsecollar, then the lights are turned off, whereupon you’re subjected to five minutes of being sneezed on, jumped on, burped on, and sometimes spit on by a hyperactive blue creature called Stitch (voiced by a guy who has evidently swallowed an entire helium balloon). If that all sounds like too much fun, don’t worry because there are plenty of laborious talking exposition scenes added to the beginning and end of this experiential show to keep it from ever getting too exciting. However, to my eyes the best part of this attraction is that the authoritarian intergalactic penal system depicted in this story could potentially inspire a lively discussion about Michel Foucault’s thesis in “Discipline and Punish” afterward. This is how you make Disney magic, people.

lively discussion about Michel Foucault’s thesis in “Discipline and Punish” afterward. This is how you make Disney magic, people.

Grade: F

Buzz Lightyear’s Space Ranger Spin

It’s a first person shooter video game layered on top of an omnimover dark ride, and it gives you a joystick that lets you spin your car in circles as much as you want, whenever you want. How can this not be fun? Well, it’s not quite as fun at the very end when they rank your final score, and I realize that where I thought I had spent the last five minutes gunning down baddies like a mofo, in reality I rated only a few levels above Helen Keller. C’mon, Disney is supposed to be the place where dreams come true, so why do they have to shatter my delusion that I have a secret special ability that can make me a ninja assassin the first time I pick up a plastic laser gun? Of course I suppose that they shouldn’t make you feel good about your high score achievements too easily because apparently there are people who really can max out the score to 999,999. At that point I say they deserve to feel truly special at the end of the ride and are free to gloat over my paltry five-digit score, because what else can such people possibly have in their life that’s good?

a mofo, in reality I rated only a few levels above Helen Keller. C’mon, Disney is supposed to be the place where dreams come true, so why do they have to shatter my delusion that I have a secret special ability that can make me a ninja assassin the first time I pick up a plastic laser gun? Of course I suppose that they shouldn’t make you feel good about your high score achievements too easily because apparently there are people who really can max out the score to 999,999. At that point I say they deserve to feel truly special at the end of the ride and are free to gloat over my paltry five-digit score, because what else can such people possibly have in their life that’s good?

Grade: C

Tomorrowland Transit Authority PeopleMover

Tomorrowland Transit Authority PeopleMover