Kuwana, Mie, Japan – Thursday, June 23rd, 2011

I didn’t like the aesthetics of this plan. Having made my way from Seoul south to Busan, then across the water to Fukuoka, then back up north to my ultimate destination in the megalopolis of Tokyo, to turn back around the day after I arrived and retrace my steps to Nagoya and Nagashima Spaland felt… ugly and inelegant. The linear progression was disrupted. The long journey was revealed to be a sham, one that could be mixed, skipped, or undone at a moment’s notice by whim or necessity. Such is the reality when visiting a country with high speed rail that’s practically too efficient.

Yet as I scanned my JR Rail Pass for a round-trip ticket from Tokyo to Nagoya early that morning, I also felt deep satisfaction. I was on a tight budget and that pass was far from cheap. While I had probably gotten the full value and then some out of it by now, this was exactly the situation that made it one of the best purchases I made that trip. The day I planned for Nagashima Spaland got completely rained out. That happens, especially in Japan in June. While my travel tech wasn’t connected enough in 2011 to make new plans on the fly, I could continue with my existing plans and, the first day of flexibility I had (and a good weather forecast in Kuwana), jump back down to try again at virtually no extra cost to me. At a ticket value of over $100, it’s an itinerary I never would have even considered if I was paying out of pocket, in which the most likely scenario was that I simply would have missed out on Japan’s largest amusement park.1

Regardless of how I got there, by 10:30 that morning I was gazing upon the towering structure of Steel Dragon 2000… again. This time with much better weather.

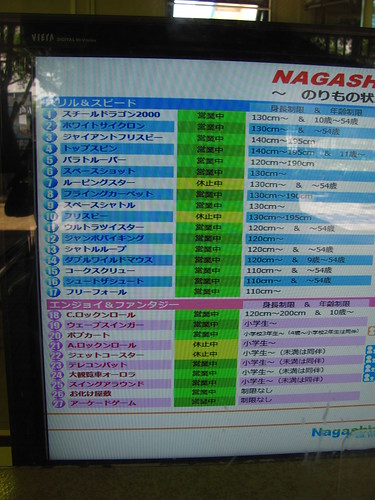

Lots of green on the big board today.

Time to finally go inside!

Nagashima Spaland is a ride park through and through. While many Asian amusement parks might make some effort to dress up individual attractions with semi-random thematic dress that mostly serve to clutter any uniform identity, Nagashima Spaland finds uniformity and consistency in its plainness. It’s a no frills, no nonsense approach to presenting the largest collection of mechanical rides in Japan, including quite possibly the largest single mechanical ride ever built. That’s not to say it’s an ugly carnival park; it’s very green throughout with some lovely views of the sea, a humble combination of both pastoral suburban parks and dense seaside parks in ways that feel familiar and welcoming, but all while pushing its iron ride game up into the stratosphere. It’s a look that’s evidence of a park that clearly knows what its core product is and is not, and it seems to be paying dividends. In 2011, the TEA/AECOM Theme Index rated Nagashima Spaland as the 16th most attended amusement park in the world with nearly six million visitors, yours truly included.2

With lots of rides to get to there was little time to waste. Unfortunately the first one I tried to go to, the classic Togo Jet Coaster, was not in operation today, becoming yet another jet coaster I’d miss in Japan. A shame too, as the trees and landscaping had grown in very densely around the track, making for what must have been an interesting ride.

Instead I ended up at Children Coaster, a Zierer Tivoli family coaster. I rode several of these around Europe the previous year, yet very few have made their way to Asia, making it a somewhat unexpected sight.

The Arrow Dynamics-built Corkscrew has been thrilling riders at Nagashima Spaland since 1979. While it’s just a basic double corkscrew design, it was enhanced somewhat by the dense foliage surrounding the track. The following year both this coaster and the neighboring Ultra Twister were relocated to the other side side of the park to make room for a new children’s section, losing most of the greenery in the process.

And here is said neighboring Ultra Twister. This was also a very good ride, possibly one of the best in the park. I didn’t spend too much time around it, as the memory of riding Greenland’s Ultra Twister Megaton 42 times in a row was still quite fresh in my memory. It felt somewhat surreal to be back again.

There are many unconventional aspects of the Togo Ultra Twister design, not least of which is the way that one of the rails cuts away inside the station to allow access into the vehicles, exposing the entire wheel assemblies to visitors as they enter.

White Cyclone was Nagashima Spaland’s Intamin-built wood coaster, opening in 1994 as the sign was sure to let you know with its very Mean Streak-inspired design. As an aside, Nagashima Spaland as a whole has frequently been compared as a Japanese version of Cedar Point, and elements like this certainly do a lot to reinforce that impression. While the two parks do share certain commonalities in their ride lineup and waterside setting, the overall vibe I got from Nagashima Spaland seemed much closer to Cedar Point in the 80’s and 90’s. I’m not sure if the comparison holds up as well when comparing the parks as they exist today.

As one of only five wood coasters remaining in Japan as of my visit (a number that is now down to just two as of this writing), White Cyclone was also at the time of my visit the third longest wooden roller coaster in the world, tracking in at over 5,500 feet long, just a hair longer than Mean Streak, and an especially impressive achievement given that it stood ‘only’ 139 feet tall.

Of course, to get that length from that height meant that White Cyclone wasn’t an especially fast ride on average, which may have been just as well since the tracking could be fairly rough at points. It seems as though Intamin decided to expand on their ideas from American Eagle at Six Flags Great America and made White Cyclone almost all big, elevated helices with a couple of large dips in between. It was far from a dynamic ride and, truth be told, not very memorable, apart from the roughness. It’s perhaps little surprise that Nagashima Spaland opted to convert White Cyclone into Asia’s first and still only hybrid coaster by Rocky Mountain Construction in 2019, once again echoing the comparisons to Cedar Point’s Mean Streak.

If there was one positive quality to White Cyclone, the enormous whitewashed wooden structure with giant spirals nestled inside certainly had a beautifully iconic look to it, especially when viewed from above on the nearby Giant Wheel Aurora, which wasn’t operating today or I would have loved to have gotten some photos for my own collection.

In any event, a quick break for some lunch-like pasta substance from the cafeteria.

After that, what better way to settle one’s stomach than a tour of Nagashima Spaland’s formidable flat and tower ride collection? Nagashima Spaland could certainly be considered the swinging ship capital of the world, with a Viking ship sitting right next to a plus-sized, double capacity Jumbo Viking ride.

And it’s not just viking ships. The Intamin Looping Starship as a Space Shuttle is another classic and increasingly rare flat ride that has found a home at Nagashima Spaland.

A Huss Giant Frisbee rounds out the pendulum ride collection while also adding another Cedar Point comparison.

A Huss Giant Frisbee rounds out the pendulum ride collection while also adding another Cedar Point comparison.

Like Cedar Point once was, Nagashima Spaland is home to both an S&S Space Shot tower and an Intamin 1st generation Free Fall drop ride. The Free Fall is still the best version of the drop tower concept. Interestingly, Japan is home to three of the five remaining 1st Gen Freefall rides in the world as of this writing.

Not a flat ride, but the Bobkart offers a quick-moving powered bobsled experience around a big open field next to Steel Dragon 2000. I don’t recall much from the ride, but I may have found the powered bobsleigh track to be poorly utilized, not fast enough to swing around the trough but more than fast enough to jolt over every seam and make for a not terribly comfortable ride. At the very least I know I only bothered to ride it once despite having two separate unique tracks.

A walk-through Haunted House experience also proved fairly forgettable, perhaps evidence of the park straying from the mechanical attractions they know best.

One often overlooked treasure is the park’s Anton Schwarzkopf made Shuttle Loop coaster, one of only six remaining, and the last remaining installation in Asia. It was one I almost missed, having been closed for most of the day before finally reopening in the final hours.

Nagashima Spaland is unique in that it’s home to two classic Schwarzkopf looping coasters, with the Looping Star also located directly next to the Shuttle Loop.

However, with quite a bit of scaffolding up around the track it was immediately clear this wasn’t one I’d get to ride today. At least it was evidence the park was taking its maintenance program seriously, and hopefully the coaster should still be around whenever I can return in the future.

The final missed coaster of the day: one half of a double Mack Rides Wild Mouse with mirrored tracks sitting side-by-side. The left side was open, the right side was closed, which is a smart way for the park to manage capacity and refurbishment schedules while only slightly annoying visiting coaster counters. I might have preferred getting right side over the left just because it’s the less common mirrored opposite of the standard model, but in terms of missed attractions on this trip this was easily towards the bottom of importance.

If Nagashima Spaland was only the attractions described above, I might not have bothered the return trip from Tokyo even with a JR Rail Pass. Since my visit the park has continued to invest in a surprising number of significant new attractions, including an S&S Free Spin, a B&M flying coaster, and an RMC Iron Horse conversion. But before all of those attractions, the ride that put Nagashima Spaland on the map and made it an unmissable destination for any coaster tour of Japan was the world’s largest roller coaster, coming in at 318 feet tall and 8,133 feet long…

Steel Dragon 2000.

As one of only two gigacoasters in the world for nearly a decade, while the height stat was what originally captured headlines—at the time the tallest full-circuit roller coaster in the world, and still the tallest lift hill in the world for fifteen years—for me it was the length statistic that captured my attention. It’s a good 1,500 feet longer than Millennium Force, and still the only roller coaster in the world to break the 8,000 foot long marker. While it’s become a cliche to note that stats alone are never the marker of a great coaster, the types of coaster I like to champion—ambitious, maybe a little ridiculous, but reaching for the sublime—usually get some above average statistics as part of the process. And in general I’ve found that length, more than any other measure, is the leading statistical indicator most highly correlated with great coaster experiences. To wit, the only other two 7,000 foot coasters, The Beast and The Ultimate, are both rides I’d call Essential. What would I end up calling Steel Dragon 2000?

“Wasteful.” Not a “complete waste,” mind you, but for all the extra there there, Steel Dragon 2000 gets very little extra out of it. A similar quality of coaster could have been achieved at much smaller scales, and indeed, it has been. The ride layout is basically the next iteration in the lineup of Morgan Manufacturing’s Cedar Fair hypercoaster series (Wild Thing, Steel Force, and Mamba) but dials up the scale by about 50% across all measures.

“Wasteful.” Not a “complete waste,” mind you, but for all the extra there there, Steel Dragon 2000 gets very little extra out of it. A similar quality of coaster could have been achieved at much smaller scales, and indeed, it has been. The ride layout is basically the next iteration in the lineup of Morgan Manufacturing’s Cedar Fair hypercoaster series (Wild Thing, Steel Force, and Mamba) but dials up the scale by about 50% across all measures.

With everything increased in equal proportion, the subject experience is quite similar to any of those three hypercoasters. If you like those rides (and in general, I do), then that’s good, because here’s one that’s the same but bigger. In some cases the extra scale does add a marginal benefit; the drop is longer and faster (but far from the visceral impact of Millennium Force’s 80 degree descent), and you get a second or two longer sustained airtime over the first camelback hill. But it’s all increases measured in fractions of a second, and any benefit to the subjective experience is pretty marginal. There are also more bunny hops on the return run. It’s a very basic, repetitive way to end a ride of this scale, but… I guess more is better than less, right?

However, the extra speed and scale tends to bog down the turnaround, which spends far too much time navigating multiple overlong inclined helices. The crisp, clean helices with sustained ground-level speed runs on Steel Force and Mamba are vastly better experiences in that regard, while Steel Dragon 2000 returns to the rather aimless, lackadaisical style of Wild Thing’s multipart turnaround. Yet also, the problem with “bigger” and “faster” is that it also usually means individual elements have longer durations to complete a change in direction while keeping the force levels safe. It doesn’t help that Steel Dragon 2000 seems to have been designed with extremely conservative force limits to begin with. Also on the negative side, the two randomly placed tunnels on the return run were both poorly ventilated and felt like briefly running through dark, dank, malodorous saunas.3

On whole, Steel Dragon 2000 still probably comes out a bit ahead of the other three Morgan hypercoasters just for the strength of the first drop and camelback hill, which is very good, but how much is that saying? It’s a gigacoaster, and the largest coaster ever built. It arrives boasting the player stats of an all-time champion, but only manages to squeak out a tight victory in the junior leagues. It’s still a good ride, but with all the vast potential it had, it wastes much of it to settle for disappointingly modest results.

It’s a gigacoaster, and the largest coaster ever built. It arrives boasting the player stats of an all-time champion, but only manages to squeak out a tight victory in the junior leagues. It’s still a good ride, but with all the vast potential it had, it wastes much of it to settle for disappointingly modest results.

And I do want to focus for a moment specifically on the idea of waste. Steel Dragon 2000 is quite literally the largest roller coaster ever built in terms of total mass, the majority of which, as the name implies, is steel. Steel is expensive stuff, as evidenced by the ride’s $52,000,000 price tag, still the highest number ever paid for an unthemed “iron ride” (much of it for earthquake protection) and that’s not counting inflation since its debut in 2000. (For comparison, Millennium Force, also considered very expensive for its time, came in at less than half the cost, $25,000,000). That’s not just an abstract number on a Japanese company’s capital expenditure report. That represents real cost in the real world, also embodying social costs, environmental costs, opportunity costs… and even then, many of those kinds of costs are externalized from the price actually paid, because capitalism. That’s not to say that we shouldn’t build big roller coasters as a society, but that when we do, at least put in the effort during the relatively low-cost design phase to make something that’s actually worth all the added expense. Steel Dragon 2000 is ambitious, yes. It’s also plainly ridiculous. But sublime? Not even close.

still the highest number ever paid for an unthemed “iron ride” (much of it for earthquake protection) and that’s not counting inflation since its debut in 2000. (For comparison, Millennium Force, also considered very expensive for its time, came in at less than half the cost, $25,000,000). That’s not just an abstract number on a Japanese company’s capital expenditure report. That represents real cost in the real world, also embodying social costs, environmental costs, opportunity costs… and even then, many of those kinds of costs are externalized from the price actually paid, because capitalism. That’s not to say that we shouldn’t build big roller coasters as a society, but that when we do, at least put in the effort during the relatively low-cost design phase to make something that’s actually worth all the added expense. Steel Dragon 2000 is ambitious, yes. It’s also plainly ridiculous. But sublime? Not even close.

Footnotes & Annotations

[1] If there was a price to pay besides rail fare, it was in missed opportunities elsewhere. While to some degree I made my plans on the fly, it’s likely if I had the extra day in Tokyo I would have used it to visit the historic suburban park Toshimaen. I later heard it described as one of the nicest, if not the best small park in Japan, with both its restraint-free 1965 Cyclone jet coaster and treasured 1907 El Dorado carousel with independently-moving concentric platforms as standouts. That Toshimaen closed at the end of 2020 without ever visiting it for myself, even when I had the chance nine years prior, it became biggest long-term disappointment from this 2011 trip.

[2] Of course, put aside the fact that to get that number, TEA/AECOM estimated a 30% attendance increase over 2010, a stunning rate of growth coinciding with the season when the entire Japanese tourist economy was reeling from natural and nuclear disasters, and necessitating a daily attendance averaging nearly 16,000 for the entire year, which to my eyes appeared at least a five-to-ten-fold inflation over the number of visitors actually present on this particular sunny summer day, and which was still vastly more than the rainy day I experienced earlier that week. Although I concede the sample size of my on-the-ground observations were just n=2 out of a total of 365, my point remains to take those numbers with a grain of salt nearly as big as Steel Dragon 2000.

[3] I should also note that Steel Dragon 2000 has since been upgraded with new custom trains by B&M. I haven’t tried them, but from the looks of things I’m not sure if they improve the ride experience. They’re more open on the sides, but they also add tall headrests to block the view in each row except the front, reduce capacity from 36 to 28 passengers, and most disappointingly add the dreaded shin holders to lock legs in place, a departure from both the typical B&M design and the original Morgan rolling stock. Those cars were big and boxy, yes, but that meant plenty of room to spread out and savor the extended floater airtime over the first camelback with nothing other than a simple round bar positioned a click or two above your thigh, the briefest glimmer that Steel Dragon ever gets to the sublime. At least the new trains should have have less risk of tossing a wheel.

Steel Dragon 2000 reminds me of when I used to play RollerCoaster Tycoon 2 when I was a lot younger. I would make custom scenarios where money was no object, and build my rollercoasters as high as the support limit would allow. As I grew older I realized this wasn’t actually making the rides *better* as the different elements and transitions don’t exactly scale up with the height of the ride. So I developed a mindset where I would stick to the 100-200ft range and focus more on creating a progression of elements that was interesting. That seems to be the ideal for real-world coasters as well, though there are still plenty of hypercoasters that make good use of their excess height.

The fact that Millennium Force can be as tall as Steel Dragon 2000, cost *half* as much to build, and still offer a compelling ride experience is the reason why it’s considered world-class. I feel like I have a new appreciation for that ride after reading this review.

That’s a good analogy, although one difference is that in RCT a reason to avoid going too big was that you’d usually just end up killing your riders with off-the-chart intensity measures, while in the case of Steel Dragon 2000 it suffers from an overly conservative approach to design. Millennium Force has much steeper drops and banked curves, and is able to do a lot more with less track than SD2000’s cautious, stretched out transitions.

It’s less “Steel Dragon 2000 looks too intense for me!” and more “I want to get off Steel Dragon 2000!”