(2010-2019)

11. MELANCHOLIA (2011)

Yes, Lars von Trier says and does controversial things. Yet it’s also possible to feel a bit of sympathy for the guy after witnessing his apocalyptic vision of life under the gravitational weight of chronic depression. Melancholia is a story in two parts, beginning with a wedding and ending with the destruction of the world. The first part is more terrifying, with the final act rendered not as horror or tragedy, but as a sublimely aesthetic fait accompli. The real strength of this film comes from its imagery, the way that it creates an unforgettable dreamlike atmosphere that, while expectedly dark given the subject matter, also offers a disquieting peacefulness and tranquility. It’s ironic that von Trier, the founder of the “Dogme 95” manifesto of cinematic realism, would now be known for films that seemingly take more inspiration from the old renaissance masters than from any cinematic tradition.

10. MEEK’S CUTOFF (2010) / CERTAIN WOMEN (2016)

Kelly Reichard is among the best (and most underrated) American directors working today. Couldn’t make up my mind. Both films feature women finding their way within the endless expanse of the American frontier, past and present. Meek’s Cutoff follows a group of settlers lost along the Oregon trail, as their intractable male leaders refuse to acknowledge the path to oblivion they are clearly set on. It’s like a slow-burn psychological horror film, and a portentous political allegory for the decade to come. Certain Women by contrast is a triptych of separate stories across present-day Montana, each in its own unique tenor (A hostage thriller, a family drama, an LGBTQ romance?), yet with numerous thematic connections linking its three leading women of a “certain” kind. While these films might be categorized as the type featuring “strong women leads,” what resonates is how the characters’ identity and agency within each story is rooted amid an overwhelming aura of uncertainty, especially in contrast to the often headstrong men around them. Both are quintessentially American films, with the Oregon high desert or the Montana plains playing a co-equal leading role. In each story, a woman finds herself thrown into this vast, ambiguous world, and asks of her the question: how does she choose to move forward from here?

Certain Women by contrast is a triptych of separate stories across present-day Montana, each in its own unique tenor (A hostage thriller, a family drama, an LGBTQ romance?), yet with numerous thematic connections linking its three leading women of a “certain” kind. While these films might be categorized as the type featuring “strong women leads,” what resonates is how the characters’ identity and agency within each story is rooted amid an overwhelming aura of uncertainty, especially in contrast to the often headstrong men around them. Both are quintessentially American films, with the Oregon high desert or the Montana plains playing a co-equal leading role. In each story, a woman finds herself thrown into this vast, ambiguous world, and asks of her the question: how does she choose to move forward from here?

9. THE LOBSTER (2015)

Yorgos Lanthimos has a directorial trademark. It’s perhaps defined by the oppressively stilted mannerisms of his actors, and has proven surprisingly flexible, with his unmistakably distinct filmography ranging from period costume dramas to suburban horror. The style finds its greatest expression in The Lobster, a kinda-sorta comedic/sci-fi/absurdist social satire, in which all single people are sent to a government-run resort and forced to pair up, or else be transformed into the animal of their choice (such as a lobster). The result was witnessing a film that simultaneously felt both unmistakably original, yet at the same time unnervingly familiar. Lanthimos takes all the too-familiar social norms around dating and marriage (or even “opposition” to those norms) and utterly defamiliarizes them. The Lobster is hilarious in the most uncomfortable of ways. Maybe it’s not so much fiction as it is a twisted reality show from our near future, when every social interaction is prescribed by law rather than convention? At least the grand prize includes a trip to the seaside…

8. US (2019)

While Get Out has gotten most of the popular acclaim for its treatment of suburban liberal racism within the context of horror movie tropes, for me it was Jordan Peele’s class-minded sophomore feature Us that registered as the more mature, urgent, and scarier film. Us manages to balance both individually existential fears and collectively political ones. The film identifies the root of our present day horrors as part of a collective amnesia over a long-buried trauma, unearthing forgotten histories at the personal and societal levels. Yes, Us is less thematically tidy than Get Out. Do those jumpsuits symbolize a communist uprising, or are they MAGA red? Neither? Both? (What about the references of absent native Americans?) The film prompts myriad questions, standing as a generational equivalent to The Shining. Plus, out of more personal gratification, theme park fans should find it rewarding to see their favored medium utilized as a key symbol within the film’s complex storytelling. “Shaman’s Vision Quest – Find Yourself!” If only real spook houses were as thematically ambitious!

7. THE GRAND BUDAPEST HOTEL (2014)

Wes Anderson is one of those directors whose critics often reduce his work to be purely about style, without considering the depth of substance beneath it, let alone how that style is directly influenced by the substance. The Grand Budapest Hotel looks like a picture book. That’s essential to understanding what this movie is about. The Grand Budapest Hotel is very much about how we choose to illustrate our lived experiences as memories, and which stories we share with (or withhold from) others. The movie begins and ends with a nesting doll narrative structure: written stories in a dusty book reveal the oral origins and the memories behind those stories, and finally the vividly lived history behind those memories, before reversing it back to the artifact at the end. The Grand Budapest Hotel combines all the best elements of a Wes Anderson story—funny, inventive, empathetic, lyrical, randomly and suddenly vulgar—but for me it’s also a poignant examination of why it’s important those stories are told and preserved in the first place.

Wes Anderson is one of those directors whose critics often reduce his work to be purely about style, without considering the depth of substance beneath it, let alone how that style is directly influenced by the substance. The Grand Budapest Hotel looks like a picture book. That’s essential to understanding what this movie is about. The Grand Budapest Hotel is very much about how we choose to illustrate our lived experiences as memories, and which stories we share with (or withhold from) others. The movie begins and ends with a nesting doll narrative structure: written stories in a dusty book reveal the oral origins and the memories behind those stories, and finally the vividly lived history behind those memories, before reversing it back to the artifact at the end. The Grand Budapest Hotel combines all the best elements of a Wes Anderson story—funny, inventive, empathetic, lyrical, randomly and suddenly vulgar—but for me it’s also a poignant examination of why it’s important those stories are told and preserved in the first place.

6. THE ACT OF KILLING (2013)

Like the previous entry, this one is also related to the existential themes of storytelling, but from a much darker place: what stories do mass murderers tell themselves so that they can live with (or maybe even celebrate) their horrific actions? This audacious documentary by Joshua Oppenheimer took the risk to find and work with the still free (and politically powerful) perpetrators of the Indonesian genocide of 1965-66. He asks them to not only recount for the camera, but even direct behind the camera their own stories of murder. The perpetrators reenact their “glorious” massacres using genre as their inspiration, from cowboy-and-Indian westerns, gangster movie interrogations, or even a surreal musical number in which their victims’ ghosts reappear in order to thank their murderers for their death. As they use cinema itself to create increasingly elaborate fictions of justification, one of the killers finally begins to contend with the moral impact of his guilt, offering a faint glimmer of clarity in a world where increasingly we all live in our own preferred realities.

5. PHANTOM THREAD (2017)

A Paul Thomas Anderson film often feels shrouded in a hazy mystery, yet there’s always an earthy realness under it that makes it so much more than just smoke and mirrors. A film isn’t a hidden message to decipher; it’s everything you see in front of you. At its surface, Phantom Thread is a movie about the push and pull of being in a romantic relationship. It’s full of rituals and superstitions, as well as unspoken but precisely choreographed interpersonal exchanges that from the outside might appear like a toxic codependency. Reynolds Woodcock (a name chosen by PTA and DDL only because, on the surface, it sounds funny) sews secret messages into his garments and keeps an excessively ordered life. Even when he’s possibly being poisoned, it’s treated with the rigor of a ritual he can’t be late for. As the audience, we can clearly see through these acts and find it all strange… but then, we get the sense that the characters can clearly see the game being played too. In the end, don’t we all need a little bit of willful superstitions in order to navigate life and love?

4. TONI ERDMANN (2016)

The plot to Maren Ade’s Toni Erdmann reads like a pitch for one of those 90’s high-concept comedies: essentially, a prankster retiree father tries to reconnect with his workaholic daughter by disguising himself with a ridiculous “self-help guru” alter ego. Yet the result, while certainly funny in its own sly ways, turns out to be one of the most emotionally wrenching critiques of late capitalism, and its psychological and interpersonal tolls, to emerge from cinema this decade. Once you think you know where it’s going, think again. The slow simmering, nearly three hour film is punctuated with several show-stopping sequences of almost delirious comedic inventiveness. Yet every flash of comedy masks an underlying sadness, regret, and, ultimately, ennui. The atmosphere is inescapable, like a fish in water. In particular the final shot (spoiler alert: nothing happens) became one of the most quietly devastating moments I’ve felt in a movie. Try as we might to break away from our roles and finally form a genuine human connection, materialism always finds a way to reassert its control.

The plot to Maren Ade’s Toni Erdmann reads like a pitch for one of those 90’s high-concept comedies: essentially, a prankster retiree father tries to reconnect with his workaholic daughter by disguising himself with a ridiculous “self-help guru” alter ego. Yet the result, while certainly funny in its own sly ways, turns out to be one of the most emotionally wrenching critiques of late capitalism, and its psychological and interpersonal tolls, to emerge from cinema this decade. Once you think you know where it’s going, think again. The slow simmering, nearly three hour film is punctuated with several show-stopping sequences of almost delirious comedic inventiveness. Yet every flash of comedy masks an underlying sadness, regret, and, ultimately, ennui. The atmosphere is inescapable, like a fish in water. In particular the final shot (spoiler alert: nothing happens) became one of the most quietly devastating moments I’ve felt in a movie. Try as we might to break away from our roles and finally form a genuine human connection, materialism always finds a way to reassert its control.

3. THE BALLAD OF BUSTER SCRUGGS (2018)

Death has always been a recurring background theme throughout the Coen brothers’ body of work, but in The Ballad of Buster Scruggs they finally made a movie that stares directly into the abyss of death itself. The Coens have directly stated that Martin Heidegger’s existential philosophy around “Being-towards-death” informed this anthology film. The theme is manifested in six different story forms, all set in the Old West, ranging from parody to comedy to allegory to parable to tragedy. What’s remarkable is how each chapter of this anthology builds upon and refines our understanding of the story that came before it, culminating in the slowly terrifying final chapter, which ultimately reflects our gaze of morbid curiosity from these stories back onto ourselves.

Death has always been a recurring background theme throughout the Coen brothers’ body of work, but in The Ballad of Buster Scruggs they finally made a movie that stares directly into the abyss of death itself. The Coens have directly stated that Martin Heidegger’s existential philosophy around “Being-towards-death” informed this anthology film. The theme is manifested in six different story forms, all set in the Old West, ranging from parody to comedy to allegory to parable to tragedy. What’s remarkable is how each chapter of this anthology builds upon and refines our understanding of the story that came before it, culminating in the slowly terrifying final chapter, which ultimately reflects our gaze of morbid curiosity from these stories back onto ourselves.

“You know the story, but people can’t get enough of them, like little children. Because, well, they connect the stories to themselves, I suppose, and we all love hearing about ourselves, so long as the people in the stories are us, but not us.

“Not us in the end, especially.”

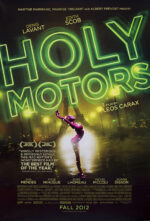

2. HOLY MOTORS (2012)

“The cinema is dead! Long live the cinema!”

I imagine this was the rallying cry behind Leos Carax’s gonzo genre-salad that is Holy Motors, his only feature film this decade. He stares down the Death of Cinema and laughs. Then cries. And then carries on. The story follows M. Oscar, an actor on a series of increasingly death- and logic-defying “appointments” across Paris, performing for invisible cameras, or perhaps for no one at all. Throughout it all, he seems haunted by a specter, perhaps of projected light through celluloid. Conjuring imagery from deep within the collective cinematic unconscious, Carax crafts a genre-bending hypnagogic odyssey that fuses monster movies, crime-thrillers, prestige dramas, Hollywood musicals, and even big-budget CGI erotica (!), among countless other inspirations. It delivers what’s simultaneously an elegiac swansong for the era of visible machines and tactile media, but also an invigorating defense of the untapped imaginative potential that moving images still have. Even as we barrel forward into another century of remakes and reboots.

1. THE MASTER (2012)

The Master isn’t really about Scientology. While Paul Thomas Anderson makes clear his opinion about the organization and its founder through his fictionalized “The Cause,” The Master takes aim at something far more fundamental about the way we construct the self. The movie hinges on the relationship between Freddie Quell and Lancaster Dodd, two of the best performances that decade. Most reviews focus on the pair’s opposing qualities, but what I find most striking is how the film goes great lengths to show just how similar they really are. What does it mean to be a master and a servant? Those two roles are bound to each other, often in flux or reversal. The tension is between the quest for freedom and the desire for belonging, and ultimately both gain neither. With no place to call home, they must make their own. The film is raw and dreamlike, earthy and enigmatic, and made with total fearlessness. What draws these two souls together, and what finally forces them apart? Just like Freddie, no matter how many times I return to The Master, I’ll still be searching for what can’t be found.

Honorable Mentions

Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives (2010)

Certified Copy (2011)

Cosmopolis (2012)

Spring Breakers (2012)

Her (2013)

Inside Llewyn Davis (2013)

Ex Machina (2014)

Anomalisa (2015)

The VVitch (2015)

The Handmaiden (2016)

Moonlight (2016)

Silence (2016)

Ladybird (2017)

The Favourite (2018)

The Lighthouse (2019)

Clean and well-maintained facilities, but some queues were quite long, impacting the overall enjoyment.